how likely is Civil War?

A 3-part quantitative adaptation of Lichtman's "Keys to the White House."

Race riots. Political polarization. 20,000 troops carry out a military occupation of American cities. The dissident right starts a third party, calling for explicit white identity, and it shocks both Democrats and Republicans, winning 5 states, and 13% of the popular vote. This sounds like the fantastical basis of a “civil war” scenario. And yet, all of these events occurred between 1948 and 1968.

The 1960s are remembered as the “radical decade,” and the 1950s are depicted as a period of relative stability and unity. There were indeed horrific race riots and significant political changes which occurred in the 1960s. The third party victories came in 1948 and 1968, not in the 1950s. Still, the radicalism of the 1950s was a necessary precondition for the 1960s.

With so much unrest, violence, polarization, and third party victories between 1948 and 1968, why didn’t America have a Civil War during this period? This is an important question, because it helps us understand how close we currently are to a Civil War in 2024. In this analysis, we will consider 1860-1861, the 1948-1968 period, and 2024. By understanding why we went to war in 1861, and why we didn’t in 1954, we can test to see how close we are in 2024.

Strong Majorities

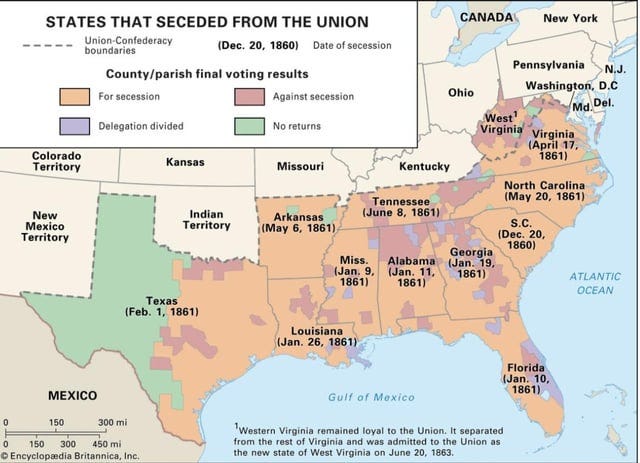

In 1860, state legislatures voted to secede from the Union. What were their margins?

South Carolina: unanimous.

North Carolina: unanimous (with one county abstaining).

Arkansas: 69-1 (99%)

Florida: 62-7 (90%)

Louisiana: 113-17 (87%)

Mississippi: 84-15 (85%)

Georgia: 209-89 (70%)

Alabama: 61-39 (69%)

Other states refused to vote outright to secede. Instead, they voted to approve a referendum on secession.

Texas: 66-7 (90%) in the legislature. Voters passed it, 46,153-14,747 (76%)

Tennessee: 66-25 (73%) in the legislature. Voters passed it, 104,471-47,183 (69%).

Virginia: 88-55 (62%) in the legislature. Voters passed it, 132,201-37,451 (78%). “West Virginia,” which was then part of Virginia, organized the Wheeling Convention to secede from the state of Virginia and remain in the union.

There were also state legislatures which held votes concerning the secession movement. Maryland and Delaware voted to remain in the Union.

Missouri and Kentucky voted for "neutrality," meaning they would neither send troops to invade the Confederacy, nor would they send troops to protect the Confederacy. Missouri’s vote was 98-1 (99%) against secession. The Kentucky state legislature refused to hold a vote regarding secession, as 76–24 (76%) of its legislature were self-identified unionists.

The Unionist victories in the Kentucky legislature were not driven by a lack of sympathy for the South, or a desire to abolish slavery, but a fear that Kentucky would become the primary battleground for the conflict. The Kentucky legislature was sympathetic to the South, but not willing to sacrifice blood for the cause.

In the absence of opinion polls, one way to examine the exact number of “Southern Sympathizers” in Kentucky is to look at the 1860 Presidential election.

Lincoln-Hamlin: 100% Unionist

Republicans, represented by Abraham Lincoln and his vice president Hannibal Hamlin, only won 0.93% of the vote in Kentucky. Not all Republicans supported abolishing slavery, but even if we assume that 100% of Republicans were against slavery, this means that 99% of voters were either opposed or lukewarm to abolitionism.

Breckinridge-Lane: 100% Confederate

John Breckinridge, alongside his vice presidential candidate Joseph Lane, represented the “secessionist mentality,” and won 36.35% of the vote in Kentucky. In this model, I assume that 100% of Breckinridge’s supporters were pro-slavery.

Bell-Everett: 70% Confederate, 30% Unionist

John Bell was a slave holder who opposed the expansion of slavery, but ended up joining the Confederacy. His vice President, Edward Everett, sided with the Union, despite not liking Lincoln personally. Bell-Everett won 45.18% of the vote in Kentucky. In this model, I assume that 70% of Bell-Everett voters went on to sympathize more with the Confederacy (whether or not they voted for or fought for secession), and 30% went on to sympathize more with the Union.

Douglas-Johnson: 70% Unionist, 30% Confederate

Stephen Douglas was a strict white supremacist who believed that white men should not kill each other over the issue of slavery. His main concern was preventing a Civil War and preserving the Union. Douglas wasn’t a slave owner like Bell, but oddly enough, his wife did own slaves.1 His vice presidential candidate, Herschel Johnson, was also a slave owner, and ended up supporting the Confederacy. Douglas ended up supporting the Union. The pair won 17.54% of the vote in Kentucky. In this model, I assume that 70% of Douglas-Johnson voters supported the Union, while 30% had implicit sympathies for the Confederacy.

The 30-70 model.

Using this 70-30 model, the total percentage of voters who were likely “Southern sympathizers” in Kentucky is 73.2%.2 What this demonstrates is that mere “sympathy” for the Southern cause was very weakly correlated with legislative victory, since an inverse proportion of the legislature (76%) was opposed to holding a referendum on secession.

It is not accurate to equate “Southern sympathy” with willingness to secede. Kentucky voters were overwhelmingly sympathetic to the South and to slave owners. Yet this 73% of “sympathizers” was not enough to translate into the kind of direct, intense support needed for war.

In Missouri, the Republican vote was much higher, at 10.28%. Using the 30-70 model, approximately 54.3% of Missouri voters were “Southern sympathizers.” The governor, Claiborne Jackson, won the 1860 governor's election with 46.95% of the vote. He maintained that he was a Unionist (in the vein of Herschel Johnson, the vice president of Douglas). But when Lincoln requested troops from him, he replied:

Your requisition, in my judgment, is illegal, unconstitutional, and revolutionary in its object, inhuman, and diabolical and cannot be complied with. Not one man will the State of Missouri furnish to carry on any unholy crusade.

Governor Jackson then secretly conspired to orchestrate a military coup to bring Missouri into the Confederacy, but he was defeated by Union forces. Despite having the power of the governor, and the fact that 54% of voters were vaguely sympathetic to the Southern cause, he was unable to overcome the state legislature and federal troops from St. Louis.

The governor’s races.

The governor was not decisive in Missouri, where his coup attempt was halted by federal forces. Could a decisive governor have altered the situation in Kentucky?

South Carolina

For reference, South Carolina was the most pro-Confederacy state. It did not have a contested governor's election between 1842 and 1860. In 1842, the two candidates were James Hammond and Robert Allston. Allston owned five plantations with 690 slaves, putting him in the top 10 slave owners in American history. Hammond, on the other hand, argued that slavery was "commanded by God," that "slavery is the corner-stone of our republican edifice," and he even attacked Thomas Jefferson:3

I repudiate, as ridiculously absurd, that much lauded but nowhere accredited dogma of Mr. Jefferson that 'all men are born equal.'

Hammond won the election with 51% of the vote. In every following election, the votes were unanimous, since votes were decided by consent of electors, not by popular vote.

Virginia

By contrast to South Carolina, Virginia was the "weakest" link in the Confederacy, with only 62% of its legislature voting for a referendum on secession. The 1859 Virginia governor's election saw the victory of John Letcher over William Goggin (52%-48%). Ironically, Letcher had previously advocated for limited abolitionism, and later repudiated his view and became pro-slavery. Goggin, on the other hand, was a unionist who later joined the Confederacy. Mixed messages indeed.

Kentucky

In 1859, Beriah Magoffin (53%) defeated Joshua Bell (47%) in Kentucky. Magoffin defended slavery, and Bell was also a slave owner. Magoffin as governor was dedicated to the cause of neutrality. When Lincoln requested troops from Kentucky, Magoffin responded in April:

I will send not a man nor a dollar for the wicked purpose of subduing my sister Southern States.

And yet, when the Confederacy requested similar help, he also refused. Magoffin did not delay or avert the participation of Kentucky for very long. By September, within five months of his refusals, both Confederate and Union troops entered Kentucky. Had Magoffin taken decisive action to join the Confederacy, it may have influenced events in other border states (such as Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri). On the other hand, had he joined the Union, the war could have ended more quickly, sparing additional lives.

Lincoln wrote about the importance of Kentucky as such:

I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol.

Kentucky saw Confederate guerrilla operations through the end of the war. Stephen Burbridge, the military commander of the District of Kentucky, issued Order 59, declaring that whenever guerrillas killed someone, four Confederate saboteurs would be removed from prison and publicly executed. The seriousness of his order demonstrates the extensive problem that Kentucky had with guerrillas.

Polarization

The two most extreme candidates in 1860 were Lincoln and Breckinridge. Lincoln’s best state was Vermont, where he won 75.86% of the vote (Breckinridge only won 4.19% of the vote there).

Breckinridge had no ballots in four states: Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. This is because, at the time, parties had to produce physical ballots to send to states, and because of the electoral college, Breckinridge decided it would be a waste of time and money to print ballots to send to these states. In three of those states, Breckinridge's voters were forced to vote for the "Fusion Party," which ostensibly represented the "anti-Lincoln vote." Pennsylvania, in addition to having a “Fusion” ballot, also allowed Douglas to appear on the ballot. Rhode Island did not have the "Fusion" Party on the ballot, but did allow Douglas.

Lincoln received no counted votes in nine states: Texas, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Tennessee. South Carolina did not use a popular vote, and if it is included, this totals 10 states. This is because:

The Republican Party did not believe they would receive a significant number of votes in places such as Alabama, South Carolina, or Mississippi. It was a waste of time and resources to send thousands of Lincoln ballots to the South, just to have them sit in unopened boxes on election day.4

By adding Lincoln together with Breckenridge, we can see what percentage of each state went for the “extremist option.” The least extreme Northern state was, ironically, Illinois, despite it being Lincoln’s home state. The least extreme Confederate state was Tennessee.

The only Confederate state which had any counted ballots for Lincoln was Virginia, where he got 1.13% of the vote.

Maryland and Delaware

Missouri and Kentucky both had significant secessionist movements which depended upon the governor. Maryland similarly lay in the hands of Governor Thomas Hicks, and Delaware was in the hands of William Burton.

In the case of Maryland, the legislature voted 53–13 on April 29, 1861, to reject any move toward succession. Hicks followed the lead of the legislature.

In the case of Delaware, Governor Burton placed control of the state militia in the hands of Henry du Pont. Du Pont owned a gunpowder factory in Wilmington, and he was educated at West Point. Du Pont would end up supplying 50% of the Union’s gunpowder throughout the war. Culturally, while Delaware was a slave state, only 1.6% of its population was enslaved, and most blacks in the state were free citizens.5

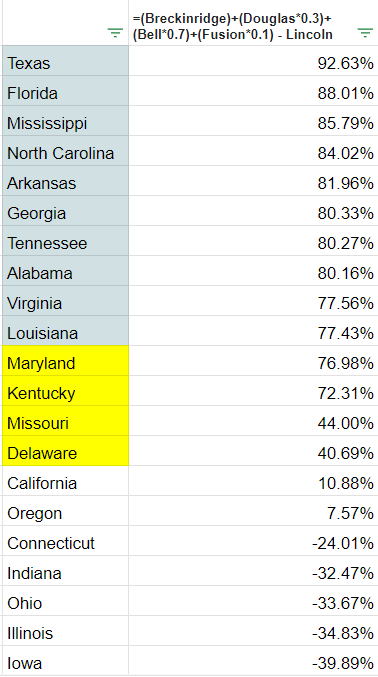

Another way to analyze the likelihood of secession is to subtract the Lincoln vote from the Breckinridge vote. In states where the Breckinridge vote exceeded the Lincoln vote by 44% (the states where he did not bother to ballot), secession was certain. The one exception was Virginia, where Breckinridge exceeded Lincoln by 43%.

States like Kentucky, Delaware, and Missouri simply did not have enough of a Breckinridge advantage over Lincoln to push for secession.

Virginia.

Virginia’s entry into the Civil War did not go smoothly. Its western counties pulled a reverse-uno card, and seceded from the secession. Had Maryland attempted to secede from the Union, it may have also seen its western counties (adjacent to West Virginia) also secede. Just as Virginia was not capable of a “clean secession,” Maryland also would not have been able to join the Confederacy easily.

Polarization… within states?

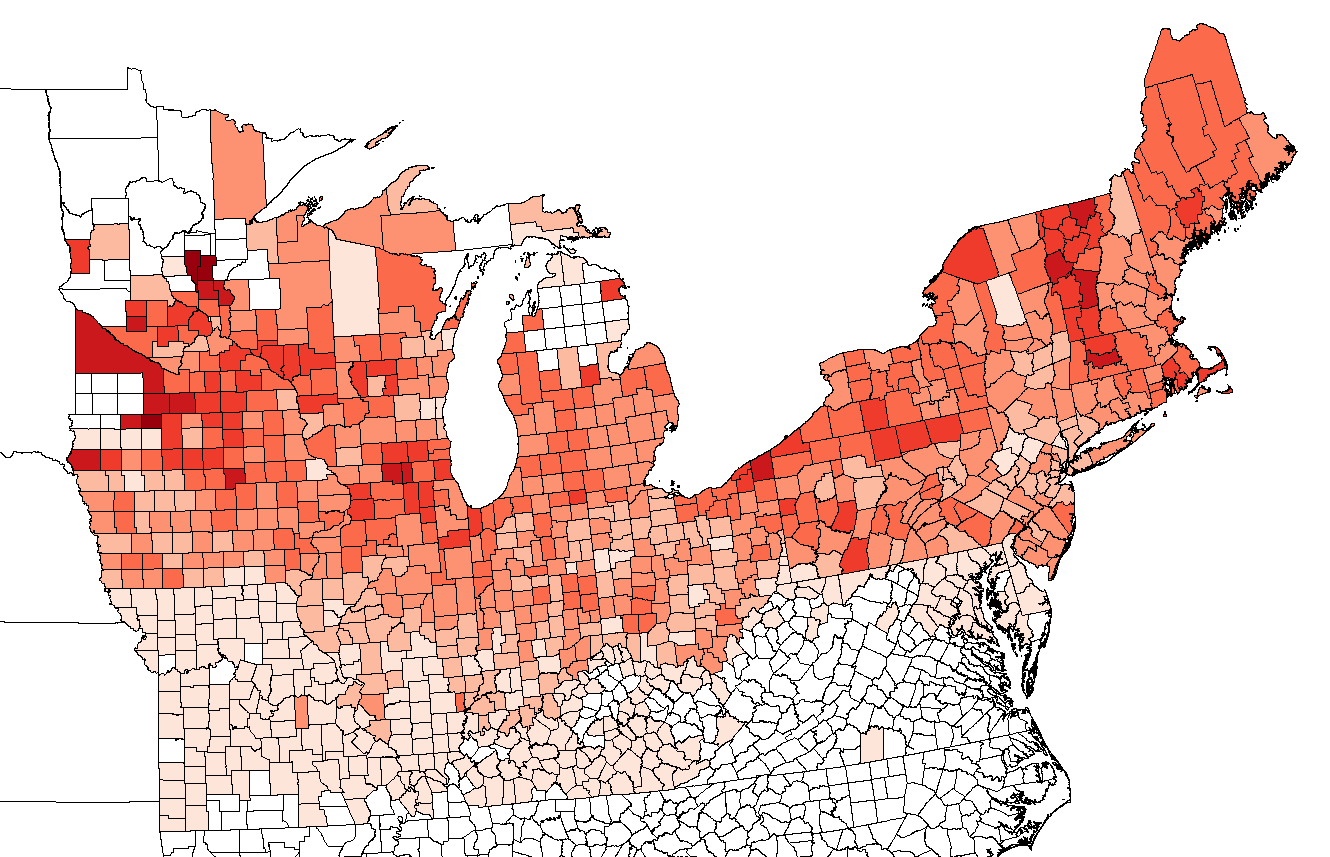

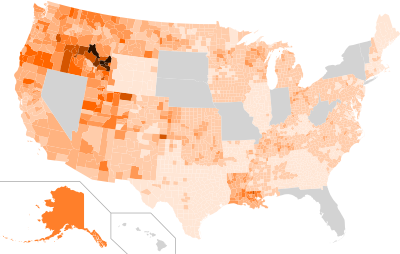

Another approach to this analysis would be to look at county level data.

How did Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia secede, despite being less pro-Breckinridge than Maryland and Delaware? Why didn’t Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, or Missouri secede?

The first and most powerful determinant was whether or not Lincoln had any ballots. Where he did not, secession was certain. There was only one state that seceded with Lincoln ballots: Virginia.

Polarization within states on a county level is important because state legislatures are made up of county representatives — they are not chosen purely according to total population, but by a sort of “internal electoral college.” In the same way that states like the Dakotas and Wyoming have disproportionate influence in the electoral college today, this was also the case within states.

This becomes significant during the meeting of state legislatures, because these were physical meetings with real people. If you have 10 legislators, and 1 of them is a pro-Lincoln extremist, that is going to foil plans for secession much more easily than if the legislature is simply split between Breckinridge legislators and Bell or Douglas legislators. This is because people seek compromise, and the presence of Lincoln legislators in an assembly (even as a small minority) was effective at dissuading secession, because of their extreme and impassioned arguments.

There are five “swing states” which had Lincoln ballots: Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware. At first glance, Virginia looks pro-Lincoln, with at least one county going for Lincoln. This makes it more pro-Lincoln (in this one county) than any county in Maryland, Kentucky, or Delaware.

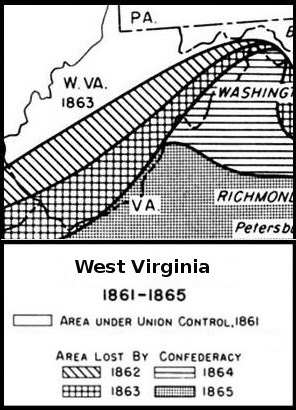

But if we exclude from Virginia those counties which became West Virginia, the picture changes.

West Virginia

“East Virginia’s” most pro-Lincoln county only went 5.28% for Lincoln. That extremely small percent meant that when the Virginia legislature met, there were practically no voices for Lincoln at all outside of West Virginia.

In Maryland and Delaware, there was no concentrated support for Breckinridge. The highest Breckinridge counties were 67% and 52%. This is in contrast to Tennessee, where enthusiasm reached as high as 85% in one county.

Another way to investigate this is to combine the Breckinridge ceiling and floor, as a measure of enthusiasm. States with a high ceiling of support, and also a high floor, could be more likely to secede. Louisiana, despite having only a Breckinridge average of 45%, had a much higher ceiling and floor than states like Missouri. What this means effectively is that support in Missouri for secession was less geographically concentrated, and also, that Missouri’s opposition to secession was geographically concentrated. This had a tremendous impact on the debates in the legislature, because the ferocity of character of each legislator was determined by the character of their home county.

Virginia’s geographic polarization.

Let’s split the election in Virginia between “East Virginia” and “West Virginia.” By using the "30-70" method of splitting the "moderate" vote, "East Virginia" was 79.8% sympathetic to the South. West Virginia wasn’t far behind, with 75.87% having Southern sympathies.

Again, the vague sensibilities, sensitivities, and sympathies of the voters was not very important or decisive. Instead, what mattered was the geographic polarization which led to various levels of “floors” and “ceilings.” Delaware had the highest floor for Breckinridge, but it did not matter much, because it also had a low ceiling. West Virginia actually had a very high ceiling for Breckinridge, but this was negated by the fact that (outside of Missouri) it had the highest vote share for Lincoln.

Compare Lincoln’s radical Republicans and Lenin’s Bolsheviks. Both of these factions never won a majority of Americans or Russians. Both of them were extremely effective as minority factions which were able to outmaneuver moderates. The same thing could be said of Mussolini’s Fascists and Hitler’s Nazis. But Bolshevism and Republicanism also shared ethnic and ideological ties. Lincoln’s strongest supporters were German revolutionaries who fled Europe after the failure of 1848. Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto, in German, in response to the 1848 Revolutions. Many of Lincoln’s generals, and Karl Marx, came from a similar ideological and European cultural milieu. Whereas Marx argued for the emancipation of the Jews from capitalism, Republicans argued for the emancipation of blacks from the institution of slavery.

No state seceded “cleanly” if Lincoln won more than 5% of the vote. While that may seem insignificant, recall that only 3% of Americans were “Patriots;” that is, they actively supported the American Revolution. Small groups of highly motivated men have an outsized influence on politics.

It is hard to imagine that 5% of West Virginian Lincolnites could overcome 43% of West Virginian Breckinridgers. But again, let’s compare this to Russia. During the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks declared a war against all religions (Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism), killing clergy and burning churches. The vast majority of Russians were religious, not atheists. The Bolsheviks only won 24% of ballots in 1918 (limited to big cities), and faced much more religious hostility from White Russians than Lincoln did from most segregationists.

The Civil War could have been much worse. Civil War generals were able to act courteously toward each other in correspondence. By contrast, it is difficult to imagine Lenin exchanging pleasantries with a White Russian gentleman. After the war was over, the Bolshevik terror was much greater and longer lasting than Reconstruction. The point here is that the Bolsheviks faced much greater odds than Lincoln voters, and still came out on top. We should not be surprised that Lincoln voters could prevent secession with only 5% of the vote. This is only a surprising result under majoritarian prejudice.

Qualitative causes.

Civil Wars aren’t just caused by opinion polls among the masses, but also by the choices of a few men, and the structure of political parties. Whereas two-party rule promotes moderating coalitions, the success of third or fourth parties (achieving more than 10% of the vote) tends to allow more extremism into politics. This has been seen in European elections like Greece, France, and Germany.

The year before the Civil War, America was divided between four parties, two of which were considered extreme and unpopular with the majority of Americans. The Republican Party, led by Lincoln, openly supported the political violence at Harper’s Ferry which most Americans saw as insane and fratricidal. The Southern Democratic Party, led by Breckinridge, openly threatened to secede, which most Americans saw as treason. Two moderate parties rose up in opposition to this extremism: the Northern Democratic Party led by Douglas, and the Constitutional Union Party led by Bell.

When the Democratic Party was united in 1856, it easily defeated the Republicans. Only when it divided (due to Buchanan’s endorsement of Breckinridge) were Republicans able to win. Lincoln could have never won a two-way race — he was considered far too radical by the majority of Americans.

The splitting of the Democratic Party occurred firstly because of regional differences (Northern Democrats vs Southern Democrats), and secondly over the issue of expanding slavery into the new western territories (Southern Democrats were committed, Constitutional Unionists sought a compromise.)

Know Nothing chaos.

Another qualitative factor is Millard Filmore’s strong Know Nothing performance in 1856. Fillmore won first or second place in 12 states. With the exception of Maryland and Delaware, all of these states would secede from the Union 5 years later. Fillmore’s success is due to the fact that radical Republicans, under the leadership of John Frémont, did not contest any elections in slave states, with the exception of Delaware, where they won 2%.

Although the Know Nothing Party avoided speaking on the issue of slavery, it could be considered a far right or extremist party that proved the potential success of a third party run. The attitudes of “anti-immigrant” and “anti-Catholic” seemed to overlap with “pro-slavery.”

The role of President James Buchanan is significant. Buchanan supported Breckinridge, destroying the Democratic party unity which had coalesced around Douglas. In his last speech to Congress, Buchanan claimed:

“The injured States, after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union.”

This amounted to a sitting President endorsing treason against the government.6

The Secretary of War, John Floyd, also argued with Buchanan about reinforcing federal forts in the South. Instead of reinforcing the federal forts, Floyd effectively smuggled guns to Confederates during the lead up to Lincoln’s inauguration. These were crucial forms of “appeasement” and “soft treason” which contributed to the ability of the South to secede.

Keys to Civil War

Given the data so far, I propose the following “keys to Civil War” (borrowing from Allan Lichtman’s “Keys to the Whitehouse”:

The seceding states must have months to prepare a military defense, and have sufficient arms to make an invasion seem daunting.

Immediately prior to secession, the incumbent president must express open sympathy for secessionism.

The incumbent Secretary of Defense must oppose defensive measures against secession.

At least 40% of states must be open to the idea of secession.

At least 20% of states must immediately secede within 3 months of each other.

“Clean” secession is only possible where:

Less than 5% of voters are committed loyalists to the federal government.

At least 40% of voters are committed to secession.

At least 75% of voters are open to the idea of secession.

It’s not fair to limit the support for secession to support for Breckinridge, since the other two Southern Parties (Douglas and Bell) ended up having their candidate or VP candidate support secession. Using the “30-70 method,” and subtracting from this the Lincoln vote, we find that in the states which successfully seceded, the “30-70” vote was, at minimum, 77.43%.

The following table is produced with this formula:

=(Breckinridge)+(Douglas*0.3)+(Bell*0.7)+(Fusion*0.1) - Lincoln

The edge cases are in Maryland, where big business and the governor were decisive, and Kentucky, where the governor was decisive. Secessionists need at least a 40% margin of victory over loyalists (70-30) to be considered “potential Confederates.” But in reality, they needed a 77% margin of victory to secure secession (88-12).

1948-1968.

Now that the events of 1860 have been clearly laid out, we can compare them with the Civil Rights era to determine how close America was to a Second Civil War.

When Strom Thurmond ran in 1948, he was able to achieve a 3/4ths supermajority in two states: Alabama and Mississippi.

However, outside these two states, Thurmond simply didn’t have the support needed to contemplate secession. In 1861, the Southern states hoped to win 14 states out of 33 to their cause, nearly a majority of the states at that time. The idea was to make it difficult enough for the North that a war would be too costly to contemplate. By contrast, Alabama and Mississippi in 1948 stood no chance of resisting federal intervention.

In 1964, Goldwater's only victory above 77% was in Mississippi, and Wallace in 1968 only won the 3/4ths supermajority in Alabama and Mississippi. In 1972, John Schmitz ran third party, and his best state was Louisiana, at 4.95%.

Wallace had planned to run in 1972, but was shot and paralyzed from the waist down by a would-be assassin.7 Two years later, he recovered from his injuries well enough to campaign from a wheelchair, and won the Alabama governor’s election with 83.2% of the vote.

Wallace was so famous that after the attempted assassination, he was visited in the hospital by President Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, George McGovern, and Ted Kennedy; and sent letters of moral support (for his good health) from Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Reagan and Pope Paul VI. Earlier, when his wife died in 1968, 25,000 people attended her funeral. By contrast, the funeral of Elvis Presley had 75,000 mourners. In the South, the Wallaces were not just a popular family, they were American heroes.

A Gallup poll in May 1972, conducted prior to the shooting, found that 19% of likely voters supported Wallace. His lowest polling number recorded was 11%. This was in line with polling in 1968, which showed him between 12% and 21% of the vote (he ultimately won 13.5% of the vote in 1968).

Schmitz, by contrast, was a nobody from California whose best state was Idaho. Rather than focusing on segregation, which was a popular issue affecting a majority of Southerners, Schmitz spoke about an international Jewish conspiracy involving the federal reserve. Still, he won 5% in Louisiana, and 9% in Idaho.

Why no secession, 1948 - 1968?

1. Weak majorities:

The Southern segregationists were strong in the South, but they still did not control 100% of their own party. Southern segregationists launched a campaign of "massive resistance," but they did not have the institutional unity to launch a violent conflict against the federal government. Whereas Breckinridge was a radical, Thurmond and Wallace were actually moderates among the segregationists (Schmitz was a true radical, and did not exceed 9% in any state).

2. Immediate action:

Buchanan and Lincoln waited and dilly-dallied to occupy Fort Sumter, giving the Confederates time to organize themselves and launch a counter-attack. Eisenhower immediately sent in thousands of battle-hardened veterans from WWII to occupy Little Rock before secession was ever on the table. No appeasement, no Civil War. Biden also took this approach at the capitol in 2020 after January 6th.

3. Successful propaganda:

Why didn't WWII vets revolt against Eisenhower's order? WWII veterans were all shown, as a matter of policy, the Why We Fight (1942) series. Why We Fight describes the Soviet Union as a worker's paradise, where ethnicities from all nations work together in harmony. Communism is depicted as an ideal model for America. Naziism and Fascism are explicitly associated with the Klan.

Another propaganda piece that was mandatory for troops to view was the film Don't Be a Sucker (1943). It describes right-wing demagogues as the internal enemies of America. It describes Jews, blacks, Catholics, and Freemasons as archetypal patriots, whereas conspiracy theorists and Klan members are depicted as traitors.

The Negro Soldier (1944) went even further in this regard, specifically linking Hitler with Jim Crow and segregation. It was the first film ever in America to depict blacks as being lawyers or athletes rather than workers or slaves. While it is less well-known today than Why We Fight and Don’t Be a Sucker, it may have ultimately had a greater impact on the politics of veterans.

Many of the GIs who watched these films were not immediately or completely convinced by their arguments. But every veteran of WWII understood the attitude of the government: pro-Jewish, pro-black, pro-Freemason, pro-communist, anti-Klan. If they didn't like that, they could have revolted at any time during WWII, but they did not. They accepted the government for what it was, and fought for it.

b. Sunk cost:

Sunk cost describes the way in which a large sacrifice for a cause engenders greater loyalty to that cause, even if it did not inspire much faith initially. In the case of WWII, most soldiers may have not initially believed that Hitler was evil, or that the Soviets were a legitimate ally, but by 1946, they looked back with a different perspective. Most veterans had friends who had died in the war.

c. Rationalizing cruelty:

Each veteran experienced hardships, but many also participated in war crimes against the civilian population. These crimes included terror bombing campaigns over Dresden, the indiscriminate killing and torture of German POWs, and the rape of German women. While paleo-conservative and anti-communist revisionist scholarship limits the scope of these crimes only to the Soviets, this is not accurate. All sides in WWII engaged in the rape of civilians, acts of terror bombing, and the illegal execution of unarmed POWs: German, Soviet, and American alike. This isn’t to suggest that all three sides were morally equivalent (they were not), but that individual soldiers later became retroactively ideologically radicalized against Naziism (and the ethnic hatred it stood for) in order to justify the cruelty of war.

Quantitatively, the majority of rapes were committed by Soviets, the majority of terror bombings were committed by the Anglo-Americans, and the majority of POW killings were committed by the Germans. But all three groups participated in all three crimes. Each side rationalized these acts of cruelty on ideological grounds: the Germans were saving Europe from Jewish Bolshevism; the Soviets saved Russia from Fascism; the Anglo-Americans saved ethnic minorities from enslavement or extermination.

Anglo-American justification for the war relied on the idea that Hitler persecuted ethnic and religious minorities as a result of his ethnocentrism and German supremacism. American propaganda films alleged that Hitler wished to kill or enslave anyone without blonde hair or blue eyes — despite the fact that many Nazis lacked those traits. The explanation for this contradiction is that the Nazis were self-hating madmen, who would eventually end up killing each other over who was more “pure” after they had destroyed the rest of the world.

Initially, American propaganda focused not on Jews, but on Hitler’s persecution of Catholics and Poles, and of the harsh conditions of the German occupation in nations like the Netherlands or Belgium. Specifically, American propaganda focused on the fact that Hitler considered Poles racially inferior, and racially impure, and thought that Germans were a Master Race.8 This is what the average American soldier believed, and they grew to oppose all forms of racism as a result. Hitler, morally, was distinguished by the fact that he was motivated by ethnic hatred. The paradox of this propaganda is that the Japanese were attacked on racist grounds, so this isn’t to say that American propaganda was logical or consistent in its morality.9

Raping and killing German civilians caused veterans to have a massive guilt complex once the war was over. This guilt complex was then rationalized away by increasing moral righteousness: we did it to fight ethnic hatred. Hitler was understood not just as killing random people, but targeting “racial inferiors” specifically. That had a huge impact on the popular perception of segregation a decade later.

The effect of this chain of logic is that by 1946, the average American veteran had a strong psychological need to oppose racial discrimination, in order to suppress the guilt they felt for their (ultimately justified) crimes in Europe.10 While most veterans did not commit these crimes personally, they witnessed or heard of them being perpetrated by fellow soldiers. Every American GI was aware of what was going on in Dresden and POW camps, and what happened to German women in occupied towns.

These secrets were hidden from the press and the American public, but not GIs. American soldiers had to dehumanize the Germans as evil in order to free them from guilt-by-association. This incentivized a strong moral prejudice against any form of ethnic discrimination.

To be clear: this isn’t to say that America was “worse than the Nazis,” or that “we shouldn’t have gone to war.” It is to say that every war produces a strong motivation for ideological justification in its participants, because every war contains some degree of unavoidable cruelty. It is impossible not to dehumanize “the enemy” during wartime. I am merely pointing out the fact that this dehumanization was consciously constructed by Hollywood to amplify desegregation, to a very successful degree.

Even without these factors, American soldiers were simply trained to do what the government told them to do, and most of them probably wouldn't have revolted in 1944 either if commanded to enforce desegregation. Although, without these propaganda factors, the possibility of some kind of military “stand down” in 1944 would have been much higher.

What about the Klan?

Why didn’t the Klan repeat the successes of 1876 by directly attacking federal forces? By 1954, the Klan no longer existed as a paramilitary force. This wasn't just because of bad PR from 1925, but because of a long and sustained media campaign against it, as well as sabotage and espionage on the part of the American government. Federal infiltrators began undermining the Klan under FDR, and HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) targeted the Klan more than any other organization.

Technically, it was not the Klan which won the battle of 1876, but the Carolina Red Shirts. These were Confederate war veterans willing to engage in terroristic guerilla warfare in the name of white supremacy. By 1954, the Klan softened its image. It rejected the term white supremacy, and preferred terms like "state’s rights." It justified segregation on the grounds of “separate but equal.”

After 1900, the Klan mostly existed as a political lobbying organization and gentleman's club, not an armed paramilitary organization. The Klan was no longer prepared to engage in a campaign of protracted guerrilla warfare, as Confederate veterans were. By 1954, almost all large paramilitary organizations were either infiltrated, investigated, prosecuted, or under the direct control of the federal government through federal informants. "Massive resistance" by the South was, as a result, pacifistic, or only capable of chaotic, disorganized violence, like the assassination of MLK.

If the Klan was a terrorist organization in 1954, then yes, there would have been a guerrilla campaign in the swamps of Alabama against Eisenhower. Dozens of federal post offices would go up in flames; federal armories would be raided; federal court houses would be flooded with Molotov cocktails and dynamite. This kind of guerrilla warfare was later advocated by James Mason in his Neo-Nazi publication Siege (1980). However, in contrast to the Redshirts and Klan of the late 19th century, this extreme rhetoric was mostly bluster and empty threats. The most violent thing Mason ever did was deploy tear gas against some black teenagers; all talk, no action. None of these racist organizations had the capacity for collective violence.11

If WWII veterans were racist, as the dissident right likes to allege, they could have easily "stood down" and rejected Eisenhower's orders. This never happened, and indicates that while Americans of this period certainly held implicit or soft racial views (a kind of NIMBY racism, still common today), they did not view race as a titanic civilizational spiritual struggle worth fighting the government or losing your job for.

2016

With the Civil War and Wallace’s Revolt considered, we will now turn our attention to 2016, and examine the claim made by Tim Pool and other conservatives that America is on the brink of Civil War.

It should be mentioned that Tim Pool, among a whole slew of conservatives “predicting” (inciting?) Civil War, was boosted and covertly funded by Russia. When we analyze the question of “how likely is Civil War?” we must acknowledge that foreign actors have an interest in distorting our perception. Of course, the government also has an interest in suppressing the idea of Civil War, so maybe those two biases cancel each other out. But at least on the dissident right, which is extremely intertwined with and vulnerable to Russian propaganda, the bias is clear. This is where the Civil War narrative is coming from. Identifying the source of the claim, however, is not enough to disprove its factual accuracy. So let’s look at some numbers.

Donald Trump in the 2016 GOP primary could be compared to a third party candidate, because he refused to endorse the winner of the primary, threatening to go third party. But Trump never won any primary with more than 50% of the vote.

If Trump’s numbers are added together with Cruz, only two states had 3/4ths supermajorities won by the “far right”: Louisiana and Mississippi. In the general election, Trump's best state was West Virginia, at 68.50%. In 2020, this switched to Wyoming, where he won 69.94%.

Does this mean we are 5% away from the 3/4ths supermajority required for a Civil War? Not quite.

In today’s America, the Keys to Civil War are as follows:

20 states would need to vote in the plurality for an open secessionist.

10 states would need to immediately secede, within 3 months. However, given the speed of information relay in 1860 (2 weeks to mail a letter), we can shorten this time scale to one week.

Each of those 10 states would need:

75% of voters open to the idea.

A hardcore base of support of 40%.

Less than 5% loyalists.

The biggest problem for secessionists today is that there is no state where Democrats make up less than 26% of the population (even Wyoming). Similarly, there are no states where Republicans make up less than 30% of the population (even Vermont).

This isn’t likely to change either, because America’s polarization is not occurring along geographic lines (North vs. South, East vs. West) but along educational lines. Whites with education vote left, whites without education vote right. While blacks and Asians do vote as a racial block, Hispanics are trending toward the center. There is no issue (besides immigration) where the parties are drifting apart. Republicans are moving left on abortion; left on LGBTQ; left on economics. Civil War-level polarization requires that parties move in opposite directions on substantive issues (not just Hunter Biden dick pic rhetoric), not that one predictably follows the other. Until Republicans start saying things like “racism is good,” as the South defended slavery, Civil War is impossible.

One caveat: Polarization isn’t based on a measurement of opinion polling of any Americans, but eligible votes. If any state removed a candidate from the ballot, or restricted the voting rights of a large percentage of the population, this would increase the likelihood of secession.

2024

2024 is shaping up to be a “race to the center,” where Kamala tries to convince voters that she is anti-immigration, and Trump tries to convince voters he is pro-choice. This is not the kind of dynamic that precedes a Civil War. Instead, Civil Wars happen when major parties suddenly shift away from compromise and toward extremism.

The greatest threat to political moderation is a third (or fourth) party victory. That does sometimes occur when the main two parties alienate their base. However, the Democrat Party seems unwilling to revolt against Kamala, and the Republicans seem unwilling to revolt against Trump. It is possible that in 2028, Trump could endorse some kind of third party candidate (having to do with RFK?) and that could create a successful third party movement. But just like Ross Perot, an RFK-style movement seems unlikely to have sufficient geographic polarization (North / South, East / West) to win any state in the electoral college. Even if RFK got second place in every single state, he wouldn’t affect the election.

It remains to be seen whether any of the current crises (economic, racial, military) could motivate Trump’s endorsement of a third party. RFK’s big issue was vaccines, but that is now irrelevant. Immigration currently seems the most polarizing issue, but if Kamala builds the wall, that issue will probably soften or slow down. I do predict that mass Asian immigration in the 21st century, from India and China, will revive the question of immigration in an entirely new way. I also predict that reproductive technologies like embryo selection and fertility counseling will have a much greater impact on future elections. But whether or not Republicans are willing to go to war against smart immigrants and reproductive choices remains to be seen.

rhetoric.

Consider the rhetoric of Owen Lovejoy, who called Lincoln his “most generous friend” and his “best friend.” He said that slave catchers belong in “the deep gorges of hell”:

[Slavery] is the doctrine of Democrats and the doctrine of devils as well, and there is no place in the universe outside the five points of hell and the Democratic Party where the practice and prevalence of such doctrines would not be a disgrace.12

There are probably Democrats who claim that Republicans are burning in hell, and likewise, there are Republicans who say the same of Democrats. But over what issue, exactly? Fantasies of pedophile cabals? Implicit racism?

Consider the following exchange by Congress members:

“I think your fake eyelashes are messing up what you’re reading.”

“That’s beneath even you, Ms. Greene.”

“How dare you attack the physical appearance of another person?”

“Are your feelings hurt?”

“Oh baby girl, don’t even play.”

“Why don’t you debate me?”

“I think it’s self-evident.”

“Yeah, you don’t have enough intelligence.”

Exchanges such as these indicate a deep level of polarization. But over what issue, specifically? Abortion? Foreign policy? Race? Religion? The economy? No — this ugly argument was started over… pornographic pictures of Hunter Biden.

This qualitative assessment is important, because not all polarization is the same. While people were willing to die to defend slavery (and to defeat it), no one is willing to go to war over Hunter Biden’s penis, or his crack habit, or his love of prostitutes. The Republican obsession with morality since Clinton is a clown show which degrades public trust, but is not likely to make Americans start killing each other.

Hunter Biden isn’t attacked as evil, but as “immodest” or “irresponsible.” Biden isn’t evil, he’s “old.” Kamala associates Trump with Hitler and Fascism, calling him a danger to democracy, but also calls him “weird.” Trump says that with Kamala in power “we won’t have a country anymore.” But if you ask him why, he’ll say it’s because she’s “stupid,” not because she’s evil.

Until major party figures are willing to call each other evil directly and unambiguously, and stop calling each other “irresponsible” or “incompetent,” the chance of a Civil War is unlikely. The Qanon claims of a “uniparty” also, ironically, help to undermine the possibility of a Civil War, by claiming that both sides are just as bad.

The closest we get to claims of evil are claims of racism. But no one in the Republican Party will defend racism by name. This is in stark contrast to the Civil War, where Southerners were absolutely willing to defend slavery. If Democrats attack Republicans as racist, and Republicans deny the charge, Civil War remains impossible over that issue.

Thanks for reading.

This article is a draft of a chapter which eventually should be edited, tightened up, and integrated into a book. It’s a bit too long for Substack. I do plan to eventually edit this and make it shorter, more concise, and easier to read.

However, for the time being, I’m not publishing it because it’s perfect. I know it could be improved. I’m publishing it because I want to start a discussion. I’m throwing things at the wall, and seeing what sticks. If a topic gets positive feedback, I will take the time to do it justice in the future.

If you’d like donate some positive feedback, it’s only $2.04 per month if you act today and get a yearly subscription. I consistently produce 3.8 articles and podcasts per week, or 16.1 per month. If you read every article, you’re only paying $0.13 cents per article. Or, if you end up only reading the top 10% very best of what I write, you’re still only paying $1.28 per article. I appreciate your support.

Talk about a mixed marriage!

(17.54*.3)+36.35+(45.18*.7)

Page 126, Selections from the Letters and Speeches of the Hon. James H. Hammond: Of South Carolina. 1866: https://books.google.com/books?id=FvMeZzrWW3AC

Page 5-8, Essah, Patience (1996). A House Divided: Slavery and Emancipation in Delaware, 1638–1865.

To be clear: Trump never endorsed treason as such. He stated that Biden stole the election. He was, at least rhetorically, defending the elected government from fraud, not openly suggesting that Republican states secede from the union. Whether or not Trump was treasonous is another matter, because treason does not require openness or honest. It is just to clarify that Buchanan is the only president who ever openly said that treason could be an acceptable course of action, and his words absolutely encouraged secession.

So no, surviving an assassination attempt does not guarantee the presidency (he dropped out).

Revisionists like Pat Buchanan and Darryl Cooper ignore the fact that Hitler honestly spelled this out in Mein Kampf.

A study on the political opinions of European vets vs. Pacific theater vets would be useful for proving this point. Rockwell fought in the Pacific theater; Eisenhower fought the Germans; but these are anecdotal figures, and some opinion polling would be good, but probably does not exist.

All omelets require broken eggs.

Racist violence actually became a reality in the 1980s and 1990s with the “lone wolf” movement. McVeigh and The Order were genuinely threatening. But this was quite late in the game. We’re focusing on secessionist movements, not any sort of terrorism.

Maybe the biggest key you're missing is the power and institutional integrity of the national standing army. It's the difference between the central government being able to simply march in and arrest those declaring secession (see the attempted secession of Catalonia from Spain around a decade ago), vs. finding that it can't do that because there's an army in its way.

One big reason secession didn't happen in the 20th century, and wasn't even seriously discussed, is that the prospects for it were militarily hopeless; it would have been suicidal in a way that secession was not in 1860-61. Thus when Eisenhower federalized the National Guard to enforce integration, those orders were obeyed, with the certain knowledge that anyone disobeying would be punished.

The US Civil War was only possible because the standing army in 1860 was tiny, about 16,000 men under arms to defend a continent, the large majority of them west of the Mississippi. This meant that the overwhelming majority of military force was going to have to be raised rapidly, relying upon state and local militias as a base. This, combined with Buchanan's indecisiveness, gave the CSA the breathing room it needed to organize an army: about 4 months between the beginning of secession and Ft. Sumter, and another 3 months until two roughly equivalent, hastily-organized armies met at Bull Run.

Of course, armies can also disintegrate when a civil war happens, which is why the army's institutional integrity is important. The US Army lost about 20% of its officers to the CSA when the Civil War started; slightly more than the CSA's share of the unenslaved population (mainly because Southerners were overrepresented in the Army). That's not ideal, but still easily survivable; a larger standing army could still easily have crushed secession in 1861 or even 1860.

The prospect of army disintegration is most relevant if a majority of the army's recruits come from groups that are not loyal to the central government. E.g. the Syrian Army, on the eve of civil war, had to rely heavily on Sunni Arabs because Alawites are something like a 15% minority. When those Sunnis deserted, the pre-war army mostly ceased to exist as a force in being.

I think the case is strong that the officers in the US military today are loyal to it and want the US to remain intact and maintain the world's most powerful military, with the world's most expensive hardware. The US military has its own culture and has worked hard to break any sense of regional identity within its units, partly out of the experience of the Civil War, and it's a lot harder for individual soldiers to defect than entire units. So my expectation is that, in the event of a serious secessionist movement, the US military would see significantly less defection than the share of the population that supports secession, and it could therefore be counted on to swiftly suppress secessionists before they were able to begin forming a competing state.

That was a fascinating article. I think you threaded the needle on "just controversial enough to make me uncomfortable" and "not actually a lunatic" very well, which is a great thing on Substack where it is not uncommon for me to realize I am subscribed to a lunatic due to the recommendation system. I would be very interested in data from other civil wars besides the American one, with the Troubles in Ireland being intuitively the most relevant example of long term civil conflict from cultural cousin.