shakespeare (could be) supreme.

platonic machiavellianism.

Glenn writes: “I agree with Sam Bankman-Fried that it’s implausible to think the greatest English writer of all time was born in 1564.”

Maybe this is a joke, but I’m going to address it as if it is serious, since SBF and Hanania have made the argument in earnest.

It is plausible that plays written in the 16th or 17th century are the greatest works of English literature, of all time.1 This is because:

Unlike science, literature does not necessarily accumulate beneficial adaptations over time.

The quality of literature is a subset of the quality of language. You cannot write great literature if your language is confined to crude constructions, “Grug kill Grog. Grug fuck Gril. Grug happy.” As the sophistication of English declines, literature is operating in a degraded context which it cannot exceed. Even if literature improves at a rate of 0.1%, if the language degrades at a rate of 0.2%, the overall quality will decrease.

Asserting that all languages, dialects, or variations of English are equal is just a form of relativism which invalidates the initial presumption that some things are better than others. It is unlikely that literature can be better or worse if language cannot be better or worse.

Shakespeare wrote during a period when literacy was reaching peak rate-of-change. This meant there was maximum pressure to perform well. After this period, literature began to decline as the percentage of geniuses in the field began to decline. This is symbolized by the shift from Shakespearean theater to Music Halls and Vaudeville.

Even if the English language had not degenerated, improvement in art is not a function of time. Most cultures throughout the world do not innovate or improve over time — stagnation is the historical norm. When culture does improve, it is due to a higher percentage of GDP being spent on culture. Between the 17th and 19th century, GDP shifted away from high-culture toward low-culture.

Fleshing out these arguments:

There’s a couple of things to address here:

How do we measure greatness?

Is literature like science? That is, does the field either uniformly improve, or at least stagnate, unless there is a massive fire or destruction of knowledge?

How long has English existed?

Everyone has a sense of greatness, but most people couldn’t offer a definition, let alone one which can be measured. Here are some attempts:

Utilitarian: the greatest of literature is determined by its positive economic, technological, or military impact on society as a whole. For example, the Bible is great because Christendom conquered Africa and America. This proves that the Bible is great literature, because it fueled vast conquests and rich economies. Of course, pagans could make the opposite argument: the Bible destroyed classical civilization, therefore it is not great.

Emotionalist: the practical or moral impact of literature is irrelevant. Instead, literature is great when it causes an emotional impact, for good or bad. If literature makes you cry and destroys your life and drives you to suicide, it is great. If literature makes you go insane and kill your family, it is great. If literature inspires you to sacrifice your life to save a small mouse, it is great. If literature doesn’t inspire you at all, or it is boring, it is not great.

Moralist: it is not enough for literature to have a powerful or emotional impact; its impact must be moral. Literature is only great when it produces good outcomes. When it produces bad outcomes, it is bad, even if those outcomes are very great in magnitude. From a Christian moral perspective, the writings of Nietzsche would be considered “not great,” even though they have “stirred souls.”

With these three definitions laid out, it is easy to see, from a Christian perspective, how the Bible could be the “greatest” of all time. Christians argue that the Bible laid a moral foundation for Christendom; it is the most touching and powerful piece of literature; it also ordered society in a cohesive and just way, which led to individual property rights, law and order, and the idealism necessary for self-sacrifice.

From a certain Jewish perspective, the New Testament is a caricature of the Tanakh. Sometimes it agrees with Jewish law, sometimes it deviates. Therefore, whatever good is found in the New Testament is merely derivative of the Tanakh. In this view, Judaism is the source of all goodness, and greater proximity to Judaism increases goodness, while distance from Judaism decreases goodness.2

From Platonic perspective, both Judaism and Christianity are rip-offs of Platonism, sourced from the Library of Alexandria. Some claim that these factions burnt the library in order to hide the evidence of their plagiarism, although the timeline on that is questionable — the first fire seems to have been a result of Caesar’s invasion of Egypt.

Pythagoreans can further claim that Plato was merely codifying the wisdom of earlier mystery schools. At this point, we seem to have receded so far back into the history of literature that we have arrived at philosophy. This makes sense from the moral perspective that “literature cannot be great without moral greatness.” In that sense, moral philosophy is a precondition for great literature.

But if we ignore morality, and focus on purely utilitarian judgments, it still seems that the goodness of literature must originate in philosophical schools. Unless one takes the view that literature is a product of divine accident, or commanded by the muses, then there must be a scientifically optimal way in which to fashion literature to achieve the best possible society. Plato argues this in The Republic, claiming that the foundation of a good state must be utilitarian myths and legends (literature) which influence the people toward maximum “justice.”

Emotionalism.

The only way to escape the philosophical origins of literature is to focus entirely on the emotional impact. In other forms of art, it seems that emotional impact can be created without any sort of analytical knowledge. Plato makes this argument in the dialogue Ion, where he claims that a poetic performer of the Iliad can create greater emotional impact while being completely ignorant of the origins or foundations of the narrative devices. For example, the performer can stir men’s hearts talking about the glories and tragedy of war, even if he has never fought in a war or seen a battle.

The ability to create emotional impact through dancing or sex requires no analytical knowledge. An illiterate person is capable of horrifying violence and torture that would traumatize any sensitive person. Life-changing sexual experiences require no literacy on the part of the partners. Why shouldn’t it be the case in literature that the greatest emotional impact could result from an expression of pure intuitive feeling, without any need for philosophical education? If this were true, then we can throw out Plato and the Bible as irrelevant to our question.

A Machiavellian Perspective

Machiavelli wrote:

“All our actions imitate nature,”

“The world, remaining continually the same, has in it a constant quantity of good and evil.”

“Men do always, but not always with reason, commend the past and condemn the present.”

“Anyone comparing the present with the past will soon perceive that in all cities and in all nations there prevail the same desires and passions as always have prevailed;… The same disorders are common to all times.”

Machiavelli is expressing the view that human nature is constant. Humans are enraged by hypocrisy; depressed by tragedy; excited by triumph; bored with repetition; stimulated with surprise; anxious in anticipation; and so on. He does so in contradiction against both progressives, who believe we can improve human nature, and also against traditionalists, who believe human nature was superior in the past. He compares humanity to any other feature of nature, which is eternal and unchanging.

This is a break with Christian soteriology, which claims that humanity goes through various stages with different relationships with God — the Adamic stage, the Antediluvian stage, the Babel stage, the Abrahamic stage, the Mosaic stage, the Davidian stage, the Rabbinic stage, the Incarnation stage, the Kingdom stage, and the Victory stage:

In the Adamic stage, man’s nature is to not know good or evil, but this changes due to the fruit.

In the Noahide stage, man’s nature is to live for hundreds of years and commit incest without consequences.

In the Babel stage, all humans speak the same language and live under a single global government.

In the Abrahamic stage, God creates the Jewish people from out of humanity, thus cleaving the souls of humans into two parts — chosen and not chosen.

In the Mosaic stage, God invents the 10 commandments, which had not yet existed.

In the Davidian stage, the divine form of government changes from judges to kings.

In the Rabbinic stage, sacrifices in the temple are no longer required for the abnegation of sins.

In the Incarnation stage, Christ is revealed and introduces a new name of God.

In the Kingdom stage, Christ rules on Earth for 1,000 years.

In the Victory stage, Satan returns for one last battle and is then destroyed, and the paradise of Eden returns forever.

Machiavelli rejects this chronology, since it implies that God is able to radically alter the conditions of man’s existence. For Machiavelli, there is no such thing as an “eternally chosen people”:

“Good and this evil shift about from one country to another... among all these races, there existed, and in some part of them there yet exists, that excellence which alone is to be desired and justly to be praised.”

Instead, there are eternal virtues which are bred into man by the exercise of religion, both pagan and Christian. In Machiavelli’s view, Christianity is no less vulnerable to the corruption of virtue than pagan religion. Machiavelli does not allow for the intervention of God in human affairs, but attributes the possibility of randomness to Fortune. Machiavelli’s theology is divided between this arbitrary Dionysian Fortuna, and the Platonic Apollonian good of Virtu.

Following this scheme, literature is composed of two features:

Adherence to the eternal virtues inherent in human nature. “Virtue” here is not synonymous with “morality,” but with “laws of power.”

Adherence to the arbitrary features of a particular language.

English is not constant. English has only existed as a language for 500-800 years. Prior to that, it was a different language, closer to a dialect of Dutch. The question is whether or not the most emotionally impactful literature could have developed 500 years ago, just as English was being formalized as a “modern” language.

If we assume that English between 1500 and 2024 hasn’t changed much at a fundamental level, then it is possible that the problem of emotionalist maximalism was “trivially” solved in Shakespeare’s time. By trivial, I don’t mean that it was easy in absolute terms, but that all the tools necessary to solve the problem were readily available.

This view is a condemnation of modern psychology and art, which claims to have grasped greater insights into emotional life. But there is no indication that advances in psychology or art have corresponded with greater emotional life, in the way that advances in medical science have proven themselves to be useful. Is life in 2024 more impactful, dramatic, or passionate than life in 1500? Perhaps for the peasantry or lower classes, there is greater opportunity to watch CGI porn and ultra-violence, although I suspect that peasant in 1500 had their fair share of sex and violence:

Cats and dogs are also less useful than other animals, and peasants will torture them just for the fun of it, just to see what will happen…

Horses are routinely beaten…

There was a case this summer in which a twenty-year-old guard at the apple orchard raped a thirteen-year-old girl. The mother of the girl—a very poor woman, it is true—agreed to forgive the offender in exchange for three rubles…

A Russian folklorist found that about 8 percent of her collection of thousands of lullabies were songs wishing death on babies, presumably weak infants like those mentioned here whose survival was uncertain and who may have been in pain…

Cases of infanticide of illegitimate babies are not at all rare. A married or unmarried woman gives birth alone somewhere in a shed, smothers the baby, and dumps it into the river (with a rock secured to its neck) or leaves it in a hemp thicket, or buries it either in the yard or somewhere in the pigpen.

Nothing seems to have changed, spiritually, among the common man, except for that which is imposed upon him by a higher type.

Since 1678, with increase in English literacy and the success of The Pilgrim’s Progress, literature has gradually lost its aristocratic orientation, and catered more and more to the masses. We should expect that the quality of literature declines over time, rather than an increase.

The series of symbols and narratives that he wove together were already optimal, and cannot be outdone. Expecting anyone to outdo Shakespeare is like expecting us to improve on 2+2=4.

The only criticism of Shakespeare remaining is that he wrote using archaic words and constructions, and since we have become dumber and the English language has degraded further and further, his plays are no longer decipherable or comprehensible to the average person. In that case, you still can’t outdo Shakespeare, because the very language itself is worse. The playing field is itself degraded and there is no possibility for excellence without abandoning the language or reforming it entirely.

Using this logic, we could even argue that Shakespeare's English was already degenerated in comparison to ancient Greek, and we should be reading Plato or the Iliad and stop wasting our time on Shakespeare. Or maybe learn Sanskrit and read the Bhagavad Gita. The whole idea of “writing a better story” seems preposterous on its face to me, since the problem at hand (manipulating human emotions) is as much a function of the excellence of the language itself as the skill of the author.

Literature is not science.

If a scientist discovers some formula or fact, as long as his knowledge is not lost or destroyed, it is maintained or built upon by other scientists. Science is insulated from degeneration. Even after Newtonian physics was overturned by quantum physics, Newtonian physics is still preserved as a useful heuristic for calculating the movements of large objects.

Literature is not at all like this. But this is the problem: scientifically minded people project their beliefs about science onto literature, when this is inapplicable and inappropriate.

Literature is generated for the purpose of an imagined audience. Unlike science, which takes an objective view of nature, to the exclusion of opinions and cultures, literature attempts to conform to, confront, or otherwise interact with subjective culture. Nature never changes, so science does not entropically degenerate. But culture certainly changes.

If we wish to be total relativists, then there is no such thing as good, better, or best literature. This Substack essay is just as good as any other. But going back to the emotionalist goal of literature, this is a problem which can be solved.

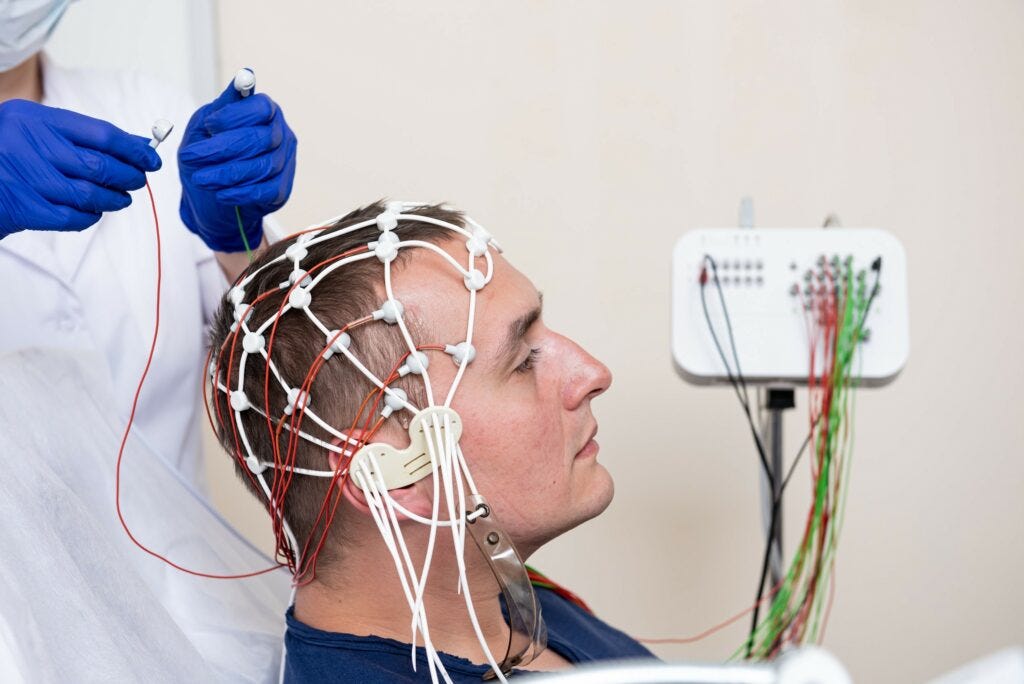

The question is now one of human quality. Let’s hook up the average American to an EEG and see what has the greatest emotional impact on them. Surely a combination of porn and violence would be the most impactful.

But violent pornography is not “good literature,” even from an emotionalist perspective. Producing the greatest emotional response from the greatest number of people is a poor measurement. If this is truly the standard for great art, then we should consider Sesame Street as the GOAT. Who as a child was not captivated by Big Bird?

Where’s the money?

In the 17th century, all the big money in entertainment was dedicated to literature and theater. In the 19th century, upper-class Protestants stopped frequenting the theater as “immoral.” As a result, the audience degenerated, and became Vaudeville and Showtunes.

In the 20th century, attention shifted toward films. Roughly $500 billion is now spent on films, as opposed to $100 billion spent on books. Only 10% of this is fiction. We shouldn’t expect an industry to improve once money and talent shifts elsewhere.

Take calligraphy or penmanship, for example. In 1776, it was the mark of a learned man to write clearly, beautifully, and neatly. In 2024, this skill no longer matters. We shouldn’t expect that calligraphy has improved in 248 just from the passage of time.

Conclusion.

I am arguing an extreme case, that Shakespeare is the best of English literature, although perhaps Chaucer is even better...

It is not necessary to go to such extreme lengths. Perhaps something written more recently is better.

Maybe you think Pride and Prejudice is better. I’ve heard some people claim that Moby-Dick is the best of American literature, and I am willing to consider that possibility while maintaining that Shakespeare is the best of the language.

Most of the supposed “greats” after the 19th century fail from an emotionalist perspective, because they become obscure and experimental in a way which detracts from the impact on the reader. James Joyce’s Ulysses is more complicated, in a certain sense, than Shakespeare, but it does not make a more efficient or powerful piece of literature.

None of this considers the degradation of utility or morality.

Science improves as more money is spent on science. If spending on science decreases, we should expect science to worsen over time. Spending on literature, as a percentage of GDP, has been decreasing with the advent of Variety Shows, Music Halls, Vaudeville, Show Tunes, and Hollywood.

Percentage of GDP is key, because percentage of GDP (not absolute GDP) is what determines the allocation of genius. There are only so many intelligent people in a given economy, and the percentage of GDP determines, to a great degree, where and how they expend their efforts. In Shakespeare’s time, aristocratic spending on literature was at an all-time high. Literacy was skyrocketing with Protestantism, and reached a “sweet spot.”

At first, increases in literacy lead to a massive increase in spending on literature as a percentage of GDP. Geniuses flock to the playwriting, and make massive advancements. But eventually, literacy increases beyond the sweet spot, and populism degrades the quality of literature. Spending veers away from high literature and toward Vaudeville black-face shows.

I could be wrong about the location of the “sweet spot.” Perhaps the sweet spot came in the 18th century, or the 19th century, or even the 20th century. But eventually, a sweet spot comes.

A weaker form of this argument would be that “greater literature than Shakespeare is being produced, but it is being drowned out by lesser literature.”

One way to empirically test these claims would be to hook up intelligent people to machines to measure their emotions and force them to read Shakespeare and something else, to see if anything could beat Shakespeare. I don’t expect this research to be conducted for want of time, money, and interest. But each of us can anecdotally, as intelligent people, read Shakespeare and compare him to other authors.

When people claim that “Shakespeare isn’t great,” they are ignoring their own bias in evaluating his language, since it is archaic, and archaic language is less impactful. I don’t spend my afternoons reading Shakespeare; I am reading WBE. There are four possibilities:

WBE is truly better than Shakespeare.

I am too dumb or lazy to understand Shakespeare.

I am trapped in the vocabulary of a degraded tongue; this inhibits my appreciation of Shakespeare.

I am insensitive to the appeal of Shakespeare because I am more akin to a peasant than an aristocrat.

The utilitarian argument for the supremacy of Shakespeare is clear. In the 16th century, England was conquering the world. Today, the politicians of the empire quibble about bathrooms, women’s sports, and whether or not we can “afford” to go to war. As if “world domination” is a luxury which we should weigh against a “sensible budget.” This is peasant-mindedness.

Clearly, the culture which produced Shakespeare was superior in nearly every way. I do not believe in “returning” to this culture, especially not via sexual puritanism, retrogressive traditionalism, or some other cargo-cult. I reject conservatism. Shakespeare wasn’t “returning” but a revolutionary. The only way to beat Shakespeare is with mass global depopulation and genetic engineering. As with everything else, human nature must itself be altered in order to overcome our predecessors.

Culture is not a “mind virus,” or a product of scientific accumulation. It is a spiritual expression of our nature, at a biological level. According to the Greeks, Homer solved the problem of literature immediately. Like Shakespeare, maybe Homer wasn’t a single person, but a group of poets working together. In either case, they figured out how to write the greatest stories ASAP. It wasn’t a slow gradual accumulation, but a violent expression of explosive genius.

When a nation or culture reaches its zenith, this is represented geographically by expansion in all directions. Although the conquests of Alexander were impressive, they did not represent an outward expansion of Greek domination to the same degree. The Greek colonies in Crimea, Egypt, Palestine, and Sicily were more significant and long-lasting than those in Afghanistan.

Similarly, the English colonial expansion in the 16th century exceeds, in relative terms (rate-of-change) anything now observed. America reluctantly supports Ukraine with less than 0.24% of its GDP. Even if America does win, this won’t mean a mass exodus of Americans to Ukraine, making Ukraine the 51st state. The last time America significantly increased its national territory was in 1900 with the annexation of Hawaii. It seems unlikely that American culture has improved in its vitality, passion, or authenticity since this period, because such virtues would be reflected in aggressive, outward, physical manifestations.

This is also true of the Islamic Golden Age, which coincided with the conquest and conversion of the Persians, Turks, and Moors. Civilizational energy is sexual energy: spermatic, ejaculatory, reproductive, fertile, assertive, confident, willful, dominant, and sado-masochistic.

It is not enough to merely “repress” sexual energy, if there is no sexual energy to begin with. The repression of a great sexual urge is masterful, as in the case of Buddha. But the repression of a weak or impotent energy is a pathetic moralistic disguise for decrepit, sclerotic, and resentful dregs.

I’ve taken some licenses in deviating from Shakespeare. Enjoy it as literature.

It’s also possible that Shakespeare’s plays were not written by Shakespeare, but by a man named Thomas North. The identity of the “Shakespeare plays” author is not my focus here.

The view that the good of Western Civilization is fundamentally derived from Judaism is espoused by Yoram Hazony. This isn’t the only Jewish perspective: historically, some Rabbis have viewed the New Testament as a perverse, satanic, or demonic inversion of the Tanakh, and the main threat to the Covenant between God and the Jewish people. By contrast, faiths like Buddhism are viewed as less existentially threatening, and perhaps even divinely inspired on some points.

Excellent analysis. As you note at the beginning of your post, we won't get anywhere in discussions of the greatest literature unless we can first agree on a definition of "greatness." Utilitarian, emotionalist, and moralist are reasonable candidates. Is there a way of conceptualizing greatness that can incorporate all three? I think so. My preference for defining good (and superlative forms such as great and excellent) is Aristotle's concept of virtue (aretê), measured by how well something performs its function. (Or, stated somewhat differently, the degree to which something brings about a desired effect.) A common example of this concept goodness or virtue is a sharp knife. The function of a knife is to cut, therefore a good (or great or excellent) knife is a sharp knife, because it cuts cleanly and easily. We don't often think about virtues in terms of the ability of something to bring about a desired effect, except in old-fashioned constructions such as "the healing virtue of this herb."

If we start with the aretê conception of goodness, the next question is, "What is the function of literature" (or, more broadly, stories or even language in general). It is probably fatuous to claim that language or stories or literature have only one function or desired effect. Language probably serves multiple functions. But allow me to focus on one possible function of stories that ties together utility, emotions, and morals, which is that stories encourage and reinforce moral behavior. My perspective on morality is that morality evolved to coordinate individuals within small social groups to cooperate with each other. This is not a novel idea; many such evolutionary conceptions of morality have been published. The mechanism by which moral behavior is motivated are our evolved moral sentiments, our species-typical emotions such as compassion, empathy, gratitude, guilt, shame, pride, disgust, and moral indignation, which encourage us to behave in cooperative ways, avoid behaving in antisocial ways, rewarding people who behave cooperatively, and punishing people who behave uncooperatively. Prosocial and antisocial behaviors lie at the heart of stories, defining protagonists, antagonists, and morally ambiguous characters (which probably most accurately describes most of us). As morally ambiguous creatures, capable of both moral and immoral behavior, we need stories to reinforce the former and discourage the latter. Stories can help accomplish this by evoking appropriate emotions, which points to the emotionalist idea of great literature.

My perspective on morality and literature has guided a long collaboration with Joe Carroll on understanding Victorian literature from an evolutionary perspective. A representative publication from our collaboration is the following:

Johnson, J. A., Carroll, J., Gottschall, J., & Kruger, D. (2011). Portrayal of personality in Victorian novels reflects modern research findings but amplifies the significance of agreeableness. Journal

of Research in Personality, 45, 50-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.011

Concerning utility, I realize that this term is often defined in economic and technological terms. But of course the utilitarian philosophers conceptualize utility in terms of how well something brings about human happiness. I would expand this conceptualization of utility to include the ability of something to bring about *any* desired effect, not just human happiness. The idea of utility as "causal efficacy" (the ability of something to bring about a desired effect) brings us full circle to the aretê conception of goodness. I have an essay on goodness as causal efficacy at https://sites.psu.edu/drj5j/real-utilitarianism/ .

None of this answers the question of whether Shakespeare wrote the greatest literature. I don't have an answer to that question, although a direction to look might be whether people behave more morally after reading Shakespeare (or any other literature one might want to study). The main point I want to make is that we need to understand the function of stories in a non-superficial way, that is, from the viewpoint of human evolution. We can superficially explain anything in terms of pleasurable and unpleasant feelings, for example, that people engage in sex because it feels good. But why do we experience some things as pleasurable and others as painful? The answer lies in the way our evolved emotions guided our ancestors toward behaviors that increased reproductive success and away from behaviors that interfered with reproductive success. My working hypothesis is that stories strike evolved emotional chords that encourage moral behavior and discourage immoral behavior, and that this has been going on since time immemorial.

My response to people who would denigrate the greatness of Shakespere would be much less "long well thought out article" and much more "act of physical violence". But thats just me