Minoritarianism, or minoritarian theory, is the study of the strategies and behavior of powerful, influential, or overrepresented minorities. The suffix "-tarian" comes from words like authoritarian, libertarian, communitarian, utilitarian, egalitarian, hereditarian, totalitarian, humanitarian, unitarian, and sectarian. It refers to "the tendency towards the rule of" minorities.1

Prescriptively, minoritarianism is the advocacy for minoritarian strategies. The suffix "ism" comes from words like nationalism, communism, liberalism, socialism, capitalism, and is frequently added to the aforementioned mentioned words: authoritarianism, libertarianism, communitarianism, utilitarianism, egalitarianism, hereditarianism, totalitarianism, humanitarianism, Unitarianism, and sectarianism.

Systems can be described as minoritarian without judging those systems as good or bad, but minoritarianism as a philosophy refers to the conscious advocacy of minority interests. It is juxtaposed with majoritarianism, which describes the tendency, especially in the European or colonial world after the 15th century, to advocate for the majority. This majority could be religious, as in the theological communism of John Ball, or political, as in the conception of Rousseau's "General Will," or ethnic, as in the development of early modern nationalism. Majoritarianism can be described as democratic, populist, representative, or folkish, and ranges from petty localism to universalism.

Religious movements often begin as minoritarian, but can become majoritarian. The puritans of England began as a minority who chafed under persecution, but upon their formation of a local majority in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, they began to persecute even smaller minorities. Jewish Americans may chafe under the threat of Trump's border wall as a symbol of nationalism, but make aliyah to Israel and oppose non-Jewish immigration. Leftists may support the ACLU and free speech when they are suffering under the electoral domination of Nixon or Reagan, but then support censorship of conservatives when they have control of social media.

The moral hypocrisy of minoritarians who become majoritarians is not limited to any particular religious, ethnic, or political minority. Rather, this hypocrisy reflects the fact that situational necessities determine moral realities, which are then unconsciously justified and rationalized until they become untenable. In edge cases, where the situation is not entirely clear, this can produce unusual contradictions. For example, American Nationalists or America First advocates waffle between loving America and hating America, making inconsistent distinctions between "the American people" and the "American regime," claiming to be pro-American but supporting China or Russia, claiming to be for the American silent majority but ignoring the fact that Trump lost the popular vote, claiming to defend the will of the people but opposing democracy, and so on. These inconsistencies proceed from the uncertainty and lack of confidence of American nationalists, who cannot decide whether they are attempting to save the country by winning elections, or destroy the government through accelerationism, sabotage, and revolution. This is reflected in the incoherency of the January 6th debacle, which was simultaneously a peaceful protest, a revolution, an antifa psyop, a fedsurrection, a demonstration of love, the persecution of patriots, the martyrdom of Ashley Babbitt, and the largest right-wing political demonstration in American history.2 All of these things cannot be simultaneously true, but exist in a Schrodinger superposition due to the inability of the American Nationalist movement to abandon the American government and embrace revolution, while at the same time being unable to embrace the American government and abandon revolution.

The incoherence or ambiguity of minority groups to determine whether they are seeking to co-opt, conquer, absorb, assimilate, dominate, undermine, subvert, or sabotage the current power structure can be viewed as proceeding from a lack of clarity of vision, but can also be viewed as a strength. Maintaining ambiguity allows for maximum flexibility in the face of changing circumstances, and allows for ideological pivoting.

Critical minoritarian theory attempts to counter minorities.

Affirmative minoritarian theory supports minoritarian interests.

Relative minoritarian theory attempts to understand the power without prescribing solutions. This includes history, anthropology, and sociology.

A critical theory of minoritarianism views minorities as threatening to the majority, and attempts to understand their strategies in order to counter them. An affirmative theory of minoritarianism views the success of a particular minority as beneficial and attempts to further the interests of that group within a majoritarian system. Lastly, a relative approach to minoritarian theory is attempting, as objectively and scientifically as possible, to understand the power dynamics of a social or political order, such as in exousiological research.3 Minoritarian theory includes history, anthropology, and sociology.

Not all minoritarian strategies are identical, but they all seek power. The three types of power, broadly, are money, military, and media. The last category is the most ambiguous, since the term media generally refers to the internet, television, radio, or newspaper media. However, in this context, a broader definition includes any dissemination of information or transmission of ideas, concepts, or attitudes which has, at minimum, an implicit impact on psychology, culture, politics, morality, or religion. This broad definition includes educational systems as a form of media, as well as church, temples, religion, public art, architecture, music, oration, poetry, propaganda, theater, ritual, customs, storytelling, drug use, dance, entertainment, cave paintings, megalithic structures, and even dietary practices. It might be simpler to call all of this "culture" as opposed to media, but the term media serves a deeper purpose of pointing towards Marshall Mcluhan's axiom, "the medium is the message."

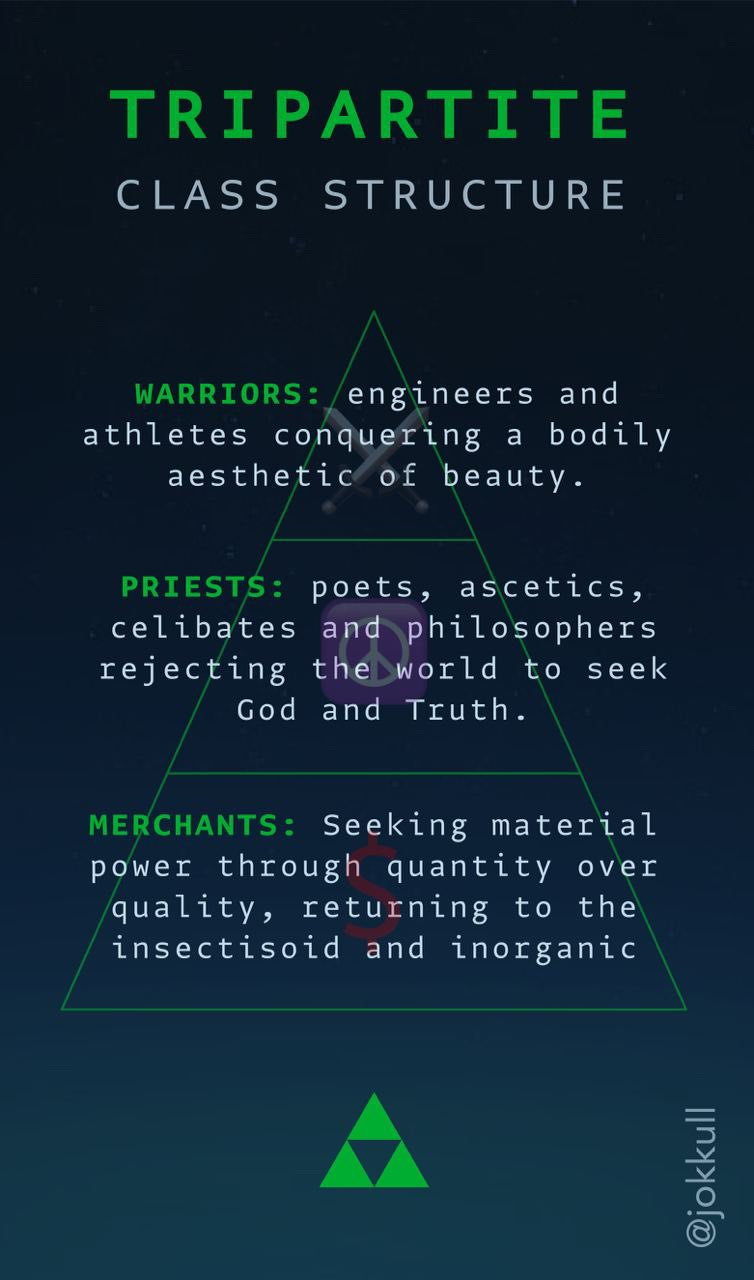

The Tripartite Structure of Minoritarianism

Specialization allows for individuals and groups to focus on one of the three aspects of power. Each minoritarian group has a different proportion of specialization in money, military, and media. A future article will list and exemplify various minoritarian groups, and highlight the various class proportions of each. However, prior to these particular and specific examples, it is necessary to understand the relationship between these three classes at the broadest historical level.

Those who focus on money are described as merchants, and in the Vedic tradition are called Vaishya. The equivocation of Vaishya with merchants is somewhat inaccurate, and this inaccuracy exists within the internal corruption of the Vedic tradition, which led early modern Indian religious movements to associate the Vaishya with other forms of mercantile activity. What distinguishes Vaishya from other merchants is that Vaishya constitute a nobility, an aristocracy, a land owning class, an administrative class, and a managerial class. The Vaishya should not be confused with broad terms like "farmer" or yeoman, as they did not work the land, but controlled a serf class which worked the land.

By contrast to Vaishya, the term "merchant" can refer to traveling salesmen, currency traders, loan agents, bankers, insurance agents, house flippers, interpreters, diplomats, messengers, scribes, accountants, tax collectors, or scam artists. Similar to the Protestant reformation in Europe which abandoned the knowledge of Latin, which then resulted in the "low church" which today accuses Plato of homosexuality, "Hinduism" as a phenomenon, while descending from the Vedic religion, often fails to distinguish between the Vaishya as a noble class and the merchant class broadly.

In medieval Europe, the aristocracy were Vaishya, in that they were landowning, and most of their wealth proceeded from agricultural activity. This was not originally the case, as the Germanic warrior class described by Tacitus and Caesar refused to engage in agricultural administration, and it was this class which conquered Rome and founded the Frankish and Carolingian dynasties from which all European nobility descend. In distinction to Vaishya, the warrior class in the Vedic tradition is called Kshatriya.

After the dramatic Germanic invasions and conquest of the western Roman Empire, this original warrior aristocracy transitioned into the role of Vaishya, but this transition was gradual and cyclical. Cycles of violence compelled the Vaishya aristocracy of Europe to once again prove itself in war, but the rise of mercenary companies in the 12th century ultimately culminated with the removal of kings from the battlefield as early as the 15th century. Whereas the period from the 5th century to the 11th century was defined by the rule of Kshatriya who only gradually and slowly adopted the role of Vaishya, the period from the 12th to 15th centuries can be described as a rapid decline in the worldview and attitude of the Kshatriya in favor of the Vaishya, culminating with the eradication of the Kshatriya as a ruling class, being subordinated to the Vaishya. This subordination of the warrior ethos to the Vaishya is the victory of feudalism over "barbarism." Mythologically, the legend of King Arthur, as opposed to the caricature of decadence as found in the "baroque," accurately reflects the distinction between the Kshatriya and Vaishya.

The invention of opera in 1597 was a conscious emulation of Greek tragedy by the Florentine Camerata. Greek tragedy itself represented the transition from the Greek foundational culture, the Homeric culture of Odysseus, to the Greek high culture. The transition between a foundational warrior culture and the establishment of a Vaishya aristocracy follows a regular pattern. The sack of Rome in 410 represents the Kshatriya founding, whereas the operatic culture of Florence in 1597 represents the victory of the Vaishya system. For the Greeks, Paul Kretschmer dates the emergence of the "Proto-Ionians" to 2000 BC and the Proto-Achaeans to 1600 BC as the first foundational Greek culture. The Dorian invasion, in this view, does not represent the founding of Greece, but can be more accurately compared to the Viking invasions which plagued northern Europe for several hundred years, which founded the province of Normandy and led to the Norman invasion of Britain. This process then concluded with the theatrical culture of Thespis in 534 BC. In both cases, the period from the Kshatriya foundation to the Vaishya domination lasts about 1,000 years.

The transition from a Kshatriya to Vaishya ruling class does not mean the end of the Kshatriya as a class, but the replacement of that class as the absolute sovereign. Alcibiades and Leonidas both could be lauded as warrior kings with Kshatriya virtues, as could Alexander the Great. Similarly, in modern Europe, soldiers and men of direct violence have risen to power, including Napoleon, Hitler, and Stalin. However, in each case, these ascensions were not foundational, in that they were short lived. Napoleon's France became a bureaucracy after his death, Hitler's reign was short lived,4 and the Soviet Union after Stalin quickly became a gerontocracy.

Thus far, the transition between a warrior aristocracy and Vaishya ruling class, the rule of military and the rule of "money," has been represented as linear and teleological. However, there is a third class which precedes both of these, which is the priest class, or Brahmin. A biological model of the evolution of the brain places physical aspects as primary, social aspects as secondary, and the ability to reason analytically and abstractly as tertiary. If we associate the Kshatriya with the physical, the Brahmin with the social, and the Vaishya with analytical thinking, then we might suspect that a theological society should follow a more primitive warrior society. Nietzsche's scheme, which places the warrior in the primary position, the priest in the secondary position, and the bourgeois "last man" in the third position, seems to follow this rubric.

However, history seems to indicate that theocracy is the default or average mode of civilization. The early states of Sumer, Egypt, Babylon all seemed to be theocracies. The later emergence of Kshatriya and Vaishya aristocracies could be aptly called a hijacking of a successful theocratic domestication. In other words, theocracies are necessary to regiment a population into submitting to a standardized, centralized authority. This religious structure domesticates and enslaves the population psychologically and spiritually, creating a class of serfs and specialized craftsmen, called Shudra. In fact, what we call the "merchant class" is generally closer to "Shudra" than to "Vaishya." Once the population is thoroughly moralized (or demoralized), it is then ready to be "hijacked" by a Kshatriya elite. The Kshatriya smash the theocratic state, but because the Shudra cry out for a new leadership, the Kshatriya assume leadership of a theocratic structure. This tension between the new warrior elite and the old religious elite generally results in conflict.

For example, in Greek myth, there is a tension between the warrior kings of Greece and the priests. Agamemnon kidnapped the daughter of a priest of Apollo, Chryses. Because Agamemnon refuses to let her go, Apollo sends a plague which is only ended when he releases the daughter. This formula bears a striking resemblance to the plagues of Yahweh, where the daughter of Yahweh, symbolically the nation of Israel, is held hostage by Egypt, and then punished by plagues. At other times in the Torah, the priests of Israel would directly confront and curse the kings of Israel.

Flavius Josephus distinguished Aaron as the priest of Israel, and Moses as the warrior king.5 This makes the class conflict evident in Numbers 12:1, "And Miriam and Aaron spake against Moses because of the Ethiopian woman whom he had married: for he had married an Ethiopian woman." Josephus claims specifically that the Ethiopian marriage was the result of the military campaigns of Moses in Ethiopia, which was excluded from later rabbinical traditions to downplay the warrior aspect of Moses in favor of priestly revisionism.

In medieval Europe, the conflict between the priest class and warrior class raged during the Investiture Contest and the Reformation. Both militant fascists and communists had later conflict with the church, but in the case of Marxism, this was a conflict between two distinct priest classes. In early medieval Europe, the church was generally forced to support one warrior aristocracy over another. The Franks were supported for being trinitarians, and once trinitarianism was well established, the Christian kings at large were supported against pagan kings.

The supportive role of the church for the warrior aristocracy, and later for the Vaishya aristocracy, has always put the church in a secondary position of protest, grievance, and complaint. Medieval Europe cannot be described as theocratic, despite the presence of theocratic elements, because the church was never the sole sovereign authority. This can be contrasted with Bronze Age civilizations, in which the priest class was the sovereign power.

It is possible that prior to the invention of agriculture, as proposed by James Frazer,6 humanity was locked in a perpetual state of theocratic superstition with no opportunity for an independent warrior or Vaishya elite. The concept of a chieftain or warrior king was always subordinated to a counsel of elders, a spiritual gerontocracy, which held up religious norms and customs as supreme over the Kshatriya. That this was overthrown, especially during the Indo-European conquests, seems to be due to the fact that an outcast warrior band, possibly exiles or criminals, or even young, irreverent men in search of adventure, did not take their priest class with them. In other words, college age men left home, left their traditions behind, became wild men and, through unprecedented military superiority, smashed theocratic states and instituted Kshatriya kingship. These kings could not be described as "secular" or "atheistic" in the modern sense, because they clearly believed in spirits, Gods, divinity, holiness and sacredness. However, the act of violation, of smashing the state, fundamentally oriented this Kshatriya elite in an entirely different direction from the priest class. This can be seen clearly in the Indo-European myths of patricide, where a son God kills the father God. It can be assumed, then, that in earlier earth mother cults, there would be no concept of "the hero slaying the dragon," but rather the dragon would be worshipped directly, and given both animal and human sacrifices. In the case of Perseus and Cetus, Greek myth makes it very clear that the Pelagasians actually worshipped the sea monster and sacrificed their children to it, and this is also clear in the myth of Abraham sacrificing Isaac.

So far, two relationships have been established: the transition between Kshatriya and Vaishya, which coincides with the emergence of "high culture," and the smashing of the Brahmin theocracy by the Kshatriya. A third relationship exists, which is that between the Vaishya and Brahmin. The Vaishya, prior to the Kshatriya patricide, had no independent existence from the Brahmin, and were united in a single theocratic-managerial class. It is only through the "secular" supremacy of the Kshatriya that it becomes possible to conceive of a "secular" Vaishya, separate from the Brahmin. In this sense, the Kshatriya overthrow creates the conditions for the Vaishya to re-emerge on a secular basis. Indeed, the first bankers of Europe, the Lombards, were descendants of Kshatriya, not Brahmin.

If we ascribe some linearity to history, assuming that there was a pre-kingly era of human existence, then Kshatriya elites emerged first between 8000 BC to 4000 BC, and continued "smashing states" up until the Norman conquest in Europe, and the period of colonization in Australia and America. Allowing for the same linearity, we can also say that an independent Vaishya class emerges as Kshatriya put down their weapons and settle in as the new "lords of the land." Again, this is not to confuse the role of merchants with Vaishya, because a merchant class which conducted international trade likely precedes this period. The distinction of Vaishya refers specifically to a dominant class, not a mere specialization in the trades.

As noted in both Greece and feudal Europe, a transition between Kshatriya and Vaishya domination occurs over the course of one thousand years, although even after the transition is "complete," there are new opportunities for temporary reversals, which we now call the "military coup." However, these do not re-create the Kshatriya values of endless, eternal war in Valhalla, and quickly regress to the Vaishya values of managerial economy. What now emerges, with the defeat of both communism and fascism, and the decline of Christianity, is a new religion of "secular universalism," with its own dominant priest class. Thus, superstitious theocracy re-emerges after thousands of years of suppression by kings and economists. If the Indo-European invasions are an inevitable recurrence, then we should expect this gerontocratic superstition to be smashed by a new Kshatriya. Fears over AI and genetic engineering may represent an accurate intuition. Large language models and genetic engineering opens up Pandora's box, much like the invention of the chariot, which cannot be contained by theological domestication and enslavement.

World on Fire (Amy Chua, 2003) examines minoritarian groups through the lens of market dominance, referencing the more common term "dominant minority." However a minoritarian group need not be dominant, but can include any "model minority" which views itself as threatened by "majoritarian" ideologies such as nationalism, theocracy, patriotism, or populism. She also does not examine the prospect of a priestly or military minoritarian strategy, but focuses on economic success.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_protests_and_demonstrations_in_the_United_States_by_size

Himmler planned to create a foundational dynasty with the SS, which he explicitly called a knightly order.

https://armstronginstitute.org/2-evidence-of-mosess-conquest-of-ethiopia

Writing his seminal works during the period 1890-1915, Frazer may have been inspired by an Enlightenment line of thought stretching from Giambattista Vico through Enlightened critics of Christianity, including Voltaire, Edward Gibbon, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. This secular approach to the superstitious roots of Christianity was elaborated on by Freud.