Are We Headed For Weimar Germany?

A historical analysis.

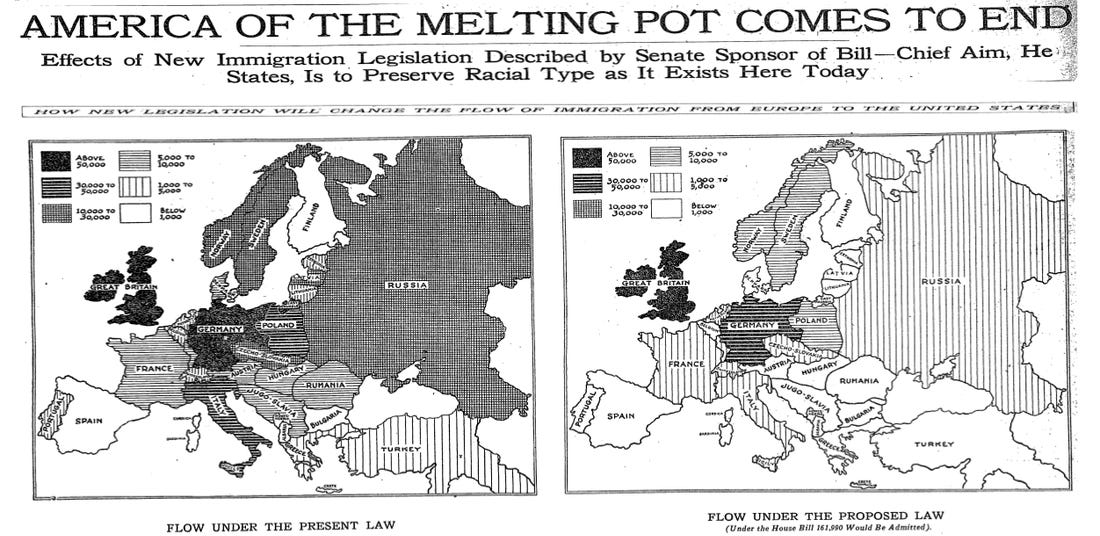

In the years between 1918 and 1932, German citizens experienced mass starvation, a wipe out of their personal savings, and a drastic increase in the rate of prostitution and sexual disease. At the same time, the Jewish population of roughly 200,000 to 500,000 was augmented by the influx of a transitory, stateless Jewish population. Most of these 2 million migrations were destined for America — however, after the 1924 Immigration Act, many eastern European Jews were denied entry to America, and remained stranded in Germany, or were deported to Poland.

Jewish Germans were not discriminated against by the 1924 Immigration Act. On the contrary, Jewish Germans were not considered separately from other Germans, and Germans on the whole were the second most favored nation after Great Britain. However, transitory Jews were not born in Germany, and did not fit into the quota. They would be counted as Polish, Russia, or Baltic, all of which were restricted to less than 10,000 per year.

The Jewish population of Britain in 1914 was roughly 250,000, and by 1933 it had only increased to 300,000, a difference of 50,000. France's Jewish population was 75,000 in 1914, but 225,000 in 1933, a difference of 150,000.

If we assume unrestricted immigration to America before 1924, then it is possible that all Jews who passed through Germany were able to find a new home in the USA, France, or Britain. However, after the passage of the 1924 Act, America limited all German immigration to a maximum of 50,000 per year. Even if Jews made up 100% of German immigrants to America, there would still be a “remainder” — that is, “transitory” Jews from eastern Europe who could not have immigrated either to Britain, France, or the USA. These Jews could attempt to survive in Germany during the period 1925 to 1933, however, given the economic collapse in 1929, this would have been extremely difficult.

Some of them may have bounced around France. For example, Herschel Grynszpan was born 1921, and his parents had moved to Germany in 1911. However, because they were recent immigrants, neither he nor his family obtained German citizenship. After the First World War, all members of the family automatically gained Polish citizenship, since that was their country of origin prior to their migration in 1911.

Despite possessing Polish citizenship, he never lived there. Instead, he was bullied as a child in Germany, and dropped out of school at age 14. At the age of 15, he illegally entered France to live with his uncle. Herschel attempted to get legal residency papers in France, but was unsuccessful. In 1938, Poland stripped all transitory persons of their citizenship, making Hershel a stateless person. He was, at this point, 17 years old, an illegal immigrant living in a ghettoized orthodox Jewish community, could not speak French, and had no education. When he heard that his family was being deported from Germany to Poland, he bought a gun, walked to the German embassy, and asked to speak with a diplomat, who he promptly shot.1 In retaliation, 90 Jews were killed, in what would later become known as Kristallnacht.

The Demographics of German Jewry

In 1910, 14.3% of Jews were foreign born.2 By 1925, that number increased to 115,000, or 23%. According to the 1944 study by Erich Rosenthal, "The aftermath of the first world war had brought an influx of 30,000 foreign Jews into Germany." 40% of all transitory Jews lived in Berlin. Jews made up 39% of Berlins total foreign-born population (with the other 60% being largely Polish).

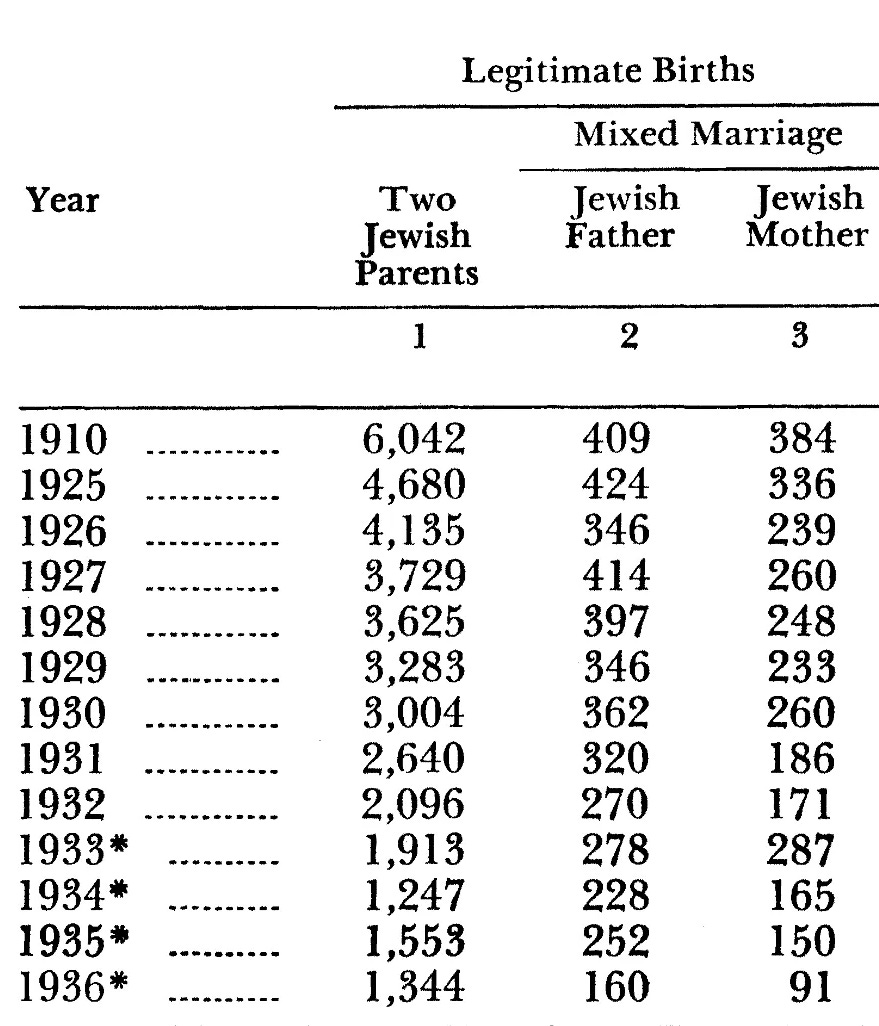

Rosenthal, as a Jewish activist, was extremely concerned that Jews were being bred out of existence by intermarriage, and low overall fertility. What now is considered a far-right concern among whites (low birth rates and mixed children) was already considered a crisis for Jews in 1944:

"Between 1910 and 1925 Prussian Jewry increased by 37,000 persons. This, however, was the result of immigration rather than of natural increase. On the basis of fertility and mortality alone — disregarding immigration — there should have been a loss of 18,000, for Jewish births declined during this period from 6,000 in the former year to 4,700 in the latter. [..] in 1934 purely Jewish births constituted only two-thirds of all Jewish births."

Rosenthal notes that "among Jews, men were more likely to migrate to the larger cities than women," because of that in "international migrations as well as in internal migrations Jewish men participate to a greater extent than Jewish women." The skewed gender ratio of the transitory Jewish population may have affected intermarriage rates, since there were “a higher proportion of Jewish husbands than Jewish wives in mixed marriages.”

The resulting picture is two-fold:

It is apparent that Jews in Weimar Germany were not especially endogamous or concerned with “racial purity,” and the trend toward intermarriage doubled and even tripled over 20 years before finally decreasing as a result of the Nuremberg Laws.

Jewish men were much more likely to marry non-Jewish women than the reverse.

All of these data points map perfectly onto the far-right anxieties of Germans during this period. Germany was experiencing uncontrolled, unregulated mass immigration from the 3rd world. To put this in perspective: the amount of immigration that Germany experienced during the interwar period would be equivalent to 10 million Mexicans passing through America on their way to Canada. Most of these migrants did not intend to remain in Germany. However, the restrictive immigration policies of Britain and the USA after 1924 meant that most of these migrants were stuck in Germany, with some of them illegally entering France.

These migrants were not accurately recorded in the statistics of the time, which only reflect Jewish citizens and Jews with official residency papers. Jews who were in Germany illegally, without papers, were not represented in official statistics, but did have a very real effect on ethnic tensions between Jews and Germans. Most of the immigrants were either extreme religious Orthodox Jews, or if they were secular, they were likely to have communist sympathies.

Rosenthal characterizes the Jews of Germany as follows:

“Life cannot be too vigorous in a group where every other person is older than 40 years, where every eighth person lives either on his income or receives social insurance benefits or relief, where every tenth person is widowed and where only every twentieth person is a child less than six years old. To be sure, this alone would justify the prediction that the group was in decline and doomed to final extinction. In the present case, however, there is collateral evidence to support a gloomy interpretation of the purely statistical data.”

Another key insight of Rosenthal is that "the dissolution of once vigorous communities through migration to the large cities prevented regular religious services." In other words, Jews were rapidly assimilating, intermarrying, secularizing, losing their religion, and therefore more open to Marxism, precisely because of their migration patterns toward mega-urbanism. Again, a majority of these Jewish internal migrants were single men who had a high rate of mixing with German women:

“Among the many informants who mentioned the extraordinary surplus of women in small Jewish communities, there was one who thus described the situation in rural Westphalia: The tabulation indicates that in these communities the female element is predominant. Unmarried spinsters and relatively young widows lead a retired, and sometimes frugal life. The youth has migrated to the cities, has turned to teaching or commercial occupations and is not interested in maintaining a family back home.

Rosenthal describes the Jewish population as one which is in decay, which has lost the will to live, which is sinking into nihilism and suicide:

Seven years before Oswald Spengler published his Decline of the West and about twenty years before Hitler assumed power, Felix Theilhaber had already brought to the attention of the public what had been known only to a few population specialists, namely that the rate of reproduction of the Jews was too low and the rate of mixed marriages too high to guarantee the future of the Jewish population in Germany.3

Besides these characterizations, which were also emphasized by the Nazis, Rosenthal notes that "Jewish manual workers were virtually absent, whereas one-fifth of the total gainful workers belonged to that class." Specifically, in 1933, whereas 19.1% of all Germans were manual workers, only 2.1% of Jews were manual workers. Rosenthal explains this by saying that “the relative absence of manual workers among the gainfully employed Jewish persons was due to their predominance in business."

One can praise Jewish Germans for being intelligent, educated, clever, or entrepreneurial, and use these virtues to explain their lack of manual labor. However, whatever your moral point of view, these facts were picked up by Nazis as a propaganda point to show that Jews existed as a class of merchants who did not do “real” work.

Having thoroughly examined Rosenthal’s 1944 report, I will now contrast it with the characterization of Yad Vashem, another Jewish source:

Among the Nobel prize winners in Germany up to 1938, 24 percent were Jews [..]. Jews played an important role in the first cabinet formed after the 1918 revolution (Hugo Hasse and Otto Landesberg), the Weimar Constitution was drafted by a Jew (Hugo Pruess), [..]. The revolutionary government in Munich was headed by a Jewish intellectual, Kurt Eisner, and after his assassination, two other Jewish leaders, Gustav Landauer and Eugen Levine, assumed positions of major influence in the “Raterepublik” (“Soviet” Republic”). Rosa Luxemburg, who was also assassinated, was a leader of the revolutionary Spartakusbund, [..] The most prominent Jewish Political figure was Walther Rathenau, who served first as minister for economic affairs and then as foreign minister.4

None of this disagrees with Rosenthal’s analysis, but provides more qualitative insight into the realities of Jewish overrepresentation in both moderate liberal as well as politically extremist movements. One area where Yad Vashem contradicts the 1944 Rosenthal report is on the question of intermarriage: “in 1927, 54% of all marriages of Jews were contracted with non-Jews.”5

Rather than dismiss Rosenthal or Yad Vashem as making an egregious or deliberate error, it is possible that Yad Vashem is counting Mischling, meaning half or quarter Jews, as part of the “Jewish population,” whereas Rosenthal is only counting marriages between people who are fully Jewish and those who are non-Jewish as mixed-marriages. David Bankier, a researcher for Yad Vashem, claims that besides the 500,000 Jews of Germany, there were also 72,000 half Jews and 39,000 quarter Jews, accounting for over 20% of German Jews. If these Jews intermarried at an extremely high rate (closer to 90%), then this would example why Rosenthal’s data differs so greatly from the data provided by Yad Vashem.6

The Migration Experience

While we have so far examined the drastic changes in Germany which resulted from mass Jewish migration, and mentioned the experience of one Jewish migrant, a more in-depth examination of the alienation inherent in the migration experience might help explain the extreme distrust and tension between native Germans and Jewish migrants.

For this purpose, I will reference Mary Antin's book, From Plotzk to Boston, as summarized by Tobias Brinkmann, of the Parkes Institute for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations. Firstly, migration was chaotic and completely uncontrolled: “the large majority of Jewish migrants [did not..] obtain a passport and [had..] to walk across the 'green border' illegally.” Antin recounts feeling entirely disoriented: “we were homeless, houseless, and friendless in a strange place."7 The experience of being loaded on and off trains, being separated by gender, stripped naked and forced into shower rooms… This sounds like something out of Auschwitz in 1943, but actually was happening in 1894:

[The] Antins boarded an overcrowded train bound for Berlin. [..] Germans, some in white overalls, rushed the migrants off the train, separated men from women and children, and threw the luggage on a big pile. Antin describes a scene of complete chaos as the bewildered and terrified migrants were driven into a small building. They were forced to undress and undergo disinfection in a primitive shower – only to be quickly hurried back onto the train which took them to Hamburg. After a two-week quarantine in what for Antin felt like a prison, the family boarded the ship to Boston where they arrived safely two weeks later. 8

Brinkmann notes, with a special relevance for the future of Jewish political activism, that the experience of Jewish refugees established a precedent for modern NGOs which facilitate mass migration:

Transnational Jewish philanthropic organizations founded in the second half of the nineteenth century put together considerable support networks for Jewish migrants in need between and across international borders. Their representatives pleaded with governments and transport companies, collected and published information in different languages, advised Jewish migrants, provided shelters and kitchens at train stations and offered financial assistance. They were important forerunners of contemporary transnational NGOs.

Brinkmann describes how Jews, fleeing war and poverty in the east, found themselves stuck in Germany, which was a miserable experience for them. In many ways, this mirrors the experience of modern African migrants who find themselves in tent camps in Calais, desiring to reach Britain:

After 1918, Jewish migrants could get off the train in Berlin and even stay for some time, but only because they often had nowhere else to go. Post-war Germany pursued a less restrictive migration policy, partly as a consequence of America's closed door policy. Initially, the Weimar Republic was simply not in a position to deport large numbers of migrants, nor to police its new borders. After the Republic had stabilized, it did not want to cause offence with its Western neighbours by deporting desperate refugees to the East.

Brinkmann does not provide examples of Jewish migrants influencing German culture. He asserts that some sort of impact was made, and cites Joseph Roth, who fought for Austria during the First World War:

Jewish migrants made important contributions to Berlin's avant-garde culture. And for a short time between 1918 and 1923 Berlin served as a vital centre of the Yiddish-speaking Jewish diaspora. But at no time was Berlin an easy place for Jewish migrants. In his 1927 essay, 'Wandering Jews', the Galician-born Jewish writer Joseph Roth described the complex topography of Jewish migration during the 1920s:

No Eastern Jew comes to Berlin voluntarily. Who, after all, comes to Berlin voluntarily? Berlin is a thoroughfare, where one stays longer because one is forced to. Berlin has no Getto. It has a Jewish quarter. Jewish emigrants come here, on their journey to America via Hamburg and Amsterdam. Quite often, they are stuck here. They have not enough money. Or their papers are not sufficient. (Of course, the papers! Half a Jewish life is wasted by the useless struggle against the papers).9

In total, the experience of Jewish migrants in Weimar Germany was extremely negative. They did not arrive as the French Huguenots, who pledged themselves loyally to serve Germany militarily. Instead, they arrived as confused and inconvenienced travelers. Their real destination and hope was America, the promised land. The impression of German workers who encountered Jewish migrants seems to have been that this population had no care or concern for the country they found themselves in. In other words, Germany was for them a big train stop that they wanted to flee as soon as possible. This negative vision colored relations in a way that statistics have trouble capturing. Instead, we will end this review by a brief bullet pointing of Weimar films:

Weimar Film

Weimar film presents a few repetitive themes: crushing poverty, the explosion of prostitution, and the overrepresentation of Jews in culture.

One of the first films in Weimar dealing explicitly with Jewish identity is The Golem: How He Came into the World (Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam, 1920). The Golem was a smash hit, which “sold out the Berlin Premiere at Ufa-Palast am Zoo on October 29, 1920, and played to full theaters for two months straight.”10 Another Jewish-centric film, The Ancient Law (Das Altes Gesetz, 1923), features a Jew who wants to escape his community and assimilate to German society. Some reviewers directly relate it to the famous Hollywood production, The Jazz Singer (1927). Graf Cohn (1923) has the same basic plot, but was less successful as a film. It should be noted that none of these Weimar “Jewish films” were perceived as antisemitic, but their success indicates a strong German focus on Jewish culture at this time.

The other films I will mention here can be split into two categories: comedies about “sinful” women, and tragedies. Some of these films are difficult to dig up, but sometimes the title conveys the emotional intention, such as The Doomed (German: Die Todgeweihten, 1924).

Under the category of “sinful” comedies go the following:

Girls You Don't Marry, 1924 (Mädchen, die man nicht heiratet).

The Girl on the Road, 1925 (Die Kleine vom Bummel) — an innocent girl goes to the big city, becomes a dancer in a club, and falls in love with a married man, and somehow it all magically works out.

The Girl with a Patron, 1925 (Das Mädchen mit der Protektion) — almost exactly like the previous film, a girl runs away to the city to be a dancer in a club.

Six Girls and a Room for the Night, 1928 (German: Sechs Mädchen suchen Nachtquartier).

The Indiscreet Woman, 1927 (Die indiskrete Frau).

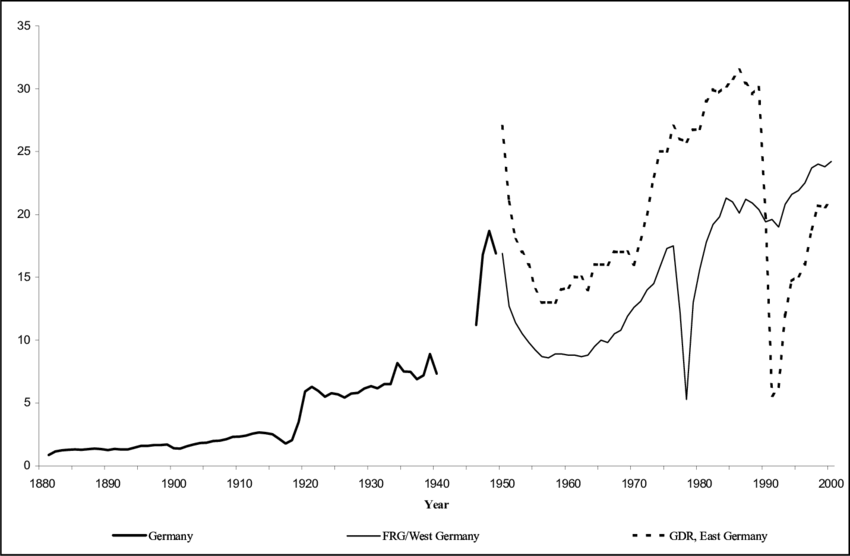

However, sometimes sin leads to tragedy. Many Weimar films deal with the problem of divorce, prostitution, infidelity, out-of-wedlock birth, and unstable marriages, which skyrocketed and more than doubled in the 1920s:

The Black Shame, 1921 (Die schwarze Schande) — a film by Carl Boese depicting the rape of white German women by African French troops.

Husbands or Lovers, 1924 (Nju – eine unverstandene Frau) — a woman has an affair, and her lover leaves her. She tries to return to her husband, but leaves her too, and she commits suicide.

The House by the Sea, 1924 (Das Haus am Meer) film) — a woman is happily married to her husband, but it is revealed that she was a former prostitute. Her husband is crushed, and she attempted suicide, but he saves her and they overcome the shame of sexual sin. The theme here is the hope that German men and women will be able to overcome sexual turmoil and instability and still find love.

The Other Woman, 1924 (German: Die Andere) — an affair goes bad.

The Morals of the Alley, 1925 (Die Moral der Gasse) — the disgrace of out of wedlock birth.

Your Desire Is Sin, 1925 (German: Dein Begehren ist Sünde).

The Dealer from Amsterdam, 1925 (Der Trödler von Amsterdam) — a woman gets mixed up in a romance with a criminal, which ends poorly.

White Slave Traffic, 1926 (Mädchenhandel – Eine internationale Gefahr) — a cautionary tale of the international human trafficking of German women by foreigners.

The Divorcée, 1926 (Die geschiedene Frau) — the threat of infidelity, which resolves in reconciliation.

The White Slave, 1927 (German: Die weisse Sklavin) — while not many German women were enslaved, the metaphor of sexual enslavement is an analogy for the perceived desperation of German’s prostitutes during the Weimar period.

Tragedy of the Street, 1927 (Dirnentragödie) — also known by the alternative title Women Without Men.

Who Invented Divorce?, 1928. (Wer das Scheiden hat erfunden).

Slums of Berlin, 1925 (German: Die Verrufenen, literally, “The Disreputables”) — The protagonist wants to put an end to his life, but is held back by Emma, a prostitute with a heart of gold.

Some films focus less on romance and more on the abject poverty of the population, and the resulting obsession with money:

All for Money, 1923 (German: Alles für Geld).

The Almighty Dollar, 1923 (Der allmächtige Dollar) — the word “Dollar” is used as an Americanism, rather than the German “Mark.”

The Last Laugh, 1924 (Der letzte Mann) — a doorman loses his job, and becomes a janitor, leading his friends and family to mock him relentlessly and reject him. He returns to the hotel to sleep in the janitor's closet. An intertitle reads: "Here our story should really end, for in actual life, the forlorn old man would have little to look forward to but death. The author took pity on him, however, and provided quite an improbable epilogue." The doorman then inherits money and lives happily ever after. Alfred Hitchcock called it an "almost perfect film."

Women of Luxury, 1925 (Luxusweibchen) is a 1925

The Woman without Money, 1925 (Die Frau ohne Geld)

Children of No Importance, 1926 (Die Unehelichen) — three poor children suffer under their violent foster parents.

Some films combined concerns with money with the breakdown of gender relations:

The Man Who Sold Himself, 1925 (Der Mann, der sich verkauft) — a man suffers divorce and a loss of money.

Joyless Street, 1925 (Die freudlose Gasse). This is one of the saddest films of all time. Women resort to prostitution to avoid starving to death.

The Marriage Swindler, 1925 (Heiratsschwindler) — scammers seduce a woman with the appearance of wealth.

Conclusion

Weimar Germany experienced a combination of mass starvation, mass sexual liberation, mass immigration, and hyperinflation. This did not happen as a single event, but a series of three waves beginning in 1918, reoccurring with the Ruhr Crisis in 1923, and then finally returning with the Great Depression of 1929. The Nazi message, which focused on “international Jews,” Lebensraum to secure the food supply, tight regulation of the banking industry, and fighting sexual degeneracy, resulted from these dramatic and abrupt crises. Without these extreme and sudden shift in material conditions, the Nazis would have likely remained polling in the single digits, similar to other far-right parties in Europe today.

What was not widely known at the time is the claim that Herschel and the diplomat he assassinated were gay lovers.

Rosenthal, Erich. (1944). Trends of the Jewish Population in Germany, 1910-39. Jewish Social Studies, 6(3), 233–274. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4464602

Rosenthal is referencing Der Untergang der deutschen Juden (Munich 1911).

From the website of Yad Vashem: https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%207794.pdf

https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%207794.pdf

Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 3, Number 1 (1988), pp. 1–20.

https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/Migration/articles/brinkmann.html

From green borders to paper walls: Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe in Germany before and after the Great War. Tobias Brinkmann, Parkes Institute for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations, University of Southampton. With reference to: Mary Antin, From Plotzk to Boston (Boston, 1899), pp. 41-43; Moderne Auswanderer [Modern Emigrants], in Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung 39 (1900), p. 612.

Also see: J. Davidson Ketchum, Ruhleben: A Prison Camp Society (Toronto, 1965).

Joseph Roth, Wandering Jews (New York, 2001), pp. 68-71. The original appeared under the title Juden auf Wanderschaft in 1927.

https://www.monmouth.edu/department-of-english/documents/containing-the-monster-the-golem-in-expressionist-film-and-theater.pdf/