There are a three popular origins of Christianity:

The Orthodox theory, that Christianity was invented by God;

The Nietzsche theory, that Christianity was invented by Jews to undermine and destroy Rome;

The Marxist theory, that Christianity was invented as an “opium for the masses,” to promote blind allegiance to authority and sheep-like attitudes to better control the people of Rome.

The theory of Nietzsche has a precedent in the writings of Schopenhauer, and the Marxist theory has a precedent in the writings of Bruno Bauer, and ultimately Hegel. In fact, both the Nietzschean theory and the Marxist theory both ultimately come from the same German philosophical movement surrounding Hegel.1

Both the Nietzschean theory and the Marxist theory are polemical and egoistic. Nietzsche opposes Christianity because he views it as a pacifying force upon the elite, whereas the Marxists opposed Christianity because they viewed it as a pacifying force upon the masses. In either cases, Christianity is a soporific which is administered by a hostile force, which must be removed in order for history to progress (or in the case of Nietzsche, to return to its barbaric roots).

Both Nietzsche and Marx see Christianity as something which threatens their ideal. For Nietzsche, the ideal man is the Ubermensch, a supreme aristocrat, a creative genius, the strong, healthy, and beautiful. For Marx, the ideal man, seemingly, is the proletarian. But underneath this veneer, the proletarian man is the man of socialism, and herein lies Marx’s distinction between socialism and communism: the proletarian man is the workhorse which achieves the prosperity of modern civilization, while the communist man is the one who reaps the fruits of civilization while being liberated from the necessity of work.

Marx opposed capitalism because he believed that capitalists were a rent-seeking class who did nothing to contribute to the pile of wealth. They were mere leeches on productive capacity, spending money on war, mink coats, and religious cathedrals. Marx believed that by eliminating the capitalist class and unleashing the true productive forces of the proletariat, all problems of economics could be eternally resolved, resulting in infinite wealth and unlimited leisure. Unlike Nietzsche, who believed that only a small minority of creative geniuses could ever enjoy leisure, Marx believed that in a communist utopia, all men would be capable of leisure and creative pursuits.

In either case, both Marx and Nietzsche are fighting for their ideal man, and they see Christianity as a threat to this man. In Jungian or Freudian terms, both Marx and Nietzsche project their Id into the animus of the ideal man, and defend him egoistically against attack.

Lastly, the Orthodox theory of Christianity generally requires that we believe in that the Bible is the Word of God — an infallible document, as established by the Church Fathers and the divine councils.

Stepping aside from these three popular theories, let us reinvestigate what the ancestors of both theories had to say about Christianity.

Ferdinand Christian Baur argued that there were two forms of Christianity: Petrine Christianity and Pauline Christianity. The distinction between these two sects is laid out by Paul in his epistles. According to Paul, the Pauline faith was threatened by “Judaizers.” These were believers in Jesus Christ who maintained adherence to Jewish law.

Marx saw Jesus as an instrument for Roman rule, and Nietzsche saw Jesus as poisoner of Rome. But in the words of Jesus: he came first for the Jews. What Jewish need did Jesus fulfill? In other words, why did Jesus come at that particular time, and not earlier or later?

From the Orthodox perspective, this question is almost irrelevant, since God’s ways are mysterious. From a sociological perspective, the historical and cultural conditions of that time are determinative.

The time period in which Jesus lived was extremely disruptive for Jewish religious life. Externally, Jews were living under military and cultural occupation from Romans, who took over from the Greeks. But internally, Jews were increasingly assimilating into Graeco-Roman culture. Assimilated Jews were called Philhellene.

Herod, the King of the Jews, was not a Jewish name. Herod comes from the Greek Herodes, from the Greek Heros. The Greek historian Herodotus is said to derive his name from Hera, although it is possible that the Greek word for “protector” is cognate with the goddess Hera.

In either case, at this time, Jews were adopting Greek names. It was also at this time that Jews began calling their temples “synagogue.” The suffix -agogue, as in pedagogue, or demagogue, means to lead. Thus, a synagogue is where the Jewish people were led together.

It is possible for us to understand how it must have felt like to be a Jew in the first century. Colonized people all over the world have lamented the loss of their native culture at the hands of colonizers. Even among whites, a small minority refer to themselves as “white nationalists,” who demand “white sovereignty” over their own culture. Whites who adopt black culture are referred to as “wiggers.”

During this time, Jewish groups formed which sought to eliminate the “wiggers” — the traitors to Jewish culture and religion. But this was not a new phenomenon. Since the destruction of the First Temple, and the exile to Babylon, Jewish prophets railed against inter-ethnic or inter-religious marriages, and against the Jewish adoption of non-Jewish culture.

Those Jews who lived during the time of Jesus suffered under the reign of three hostile foreign dominant cultures: the Persian, the Greek, and the Roman. In each case, the Jewish theological explanation for this state of affairs is that God was punishing the Jewish people for their misdeeds, for breaking the rules of the covenant.

Each time the Jewish people were subjugated, the religious explanation was that Jews were not loyal to God, and needed to return to Jewish law. As a result, by the time of Jesus, various Jewish factions competed over who was more “law abiding.” Of these, the Pharisees were the most prominent. On the other hand, some Jewish factions were tempted toward integration with the surrounding culture. Those who integrated with the pre-existing Canaanite culture (generally through marriage) were referred to as Samaritans, while those who integrated into Greek culture were Hellenistic Jews.

The schism between the Jewish right, the conservatives who wanted to return to tradition, and the Jewish left, the open-minded progressives who wanted to be modern, ecumenical, and philosophical, was extremely polarized. After the destruction of the Second Temple, the Sicarii sought to assassinate both Romans as well as Jews who were insufficiently devout. This kind of resistance is similar to the German werewolves, a partisan group that sought to fight on after Germany was crushed.

Jesus was firmly on the side of the left. However, as with any leftist political movement, there were reactionaries who attempted to co-opt Jesus’s teachings and soften or moderate them. These were what Paul called “Judaizers.” They were fine with Jesus being God — that was all well and good. But the Sabbath must be kept holy, circumcision must continue, and food must be kosher.

Had the Judaizers succeeded, Christianity would have remained an exclusively Jewish religion. It would not proselyte or evangelize the nations. Christianity would have represented a significant departure from previous forms of Judaism, in that it claimed that God incarnated on earth, but it would not fulfill the commission of the Holy Spirit, the Pentecost, speaking in tongues — not just babbling, but actually learning other languages to convert foreigners.

It is possible that this sort of “Christianity” was essentially already practiced by John the Baptist. The Baptist religion began as an entirely Jewish affair, and its innovation likely involved inducing hallucinatory states through near-drowning experiences. Jesus was able to join in with these people, and added on his theology on top of theirs. In this way, it is clear that Judaism was already mutating rapidly and evolving different sects even prior to the coming of Jesus. All of this was due to the massive psychological pressure of the dominance of Graeco-Roman culture over a previously free and sovereign people.

One of the ways to think about the extreme mutations in the Jewish religion during this time period is to compare them to the outbreak of Bolshevism in Russia, or National Socialism in Germany. In both cases, societies were experiencing massive social change and unrest, where the traditional authorities were being questioned. The result was the success of ideas which were previously thought of as extreme.

An alternative view on Jesus is that he, like John the Baptist, was Petrine — that is, he did not seek to convert the gentiles. The Pentecost, in this view, would not be an extension of Jesus’s teachings, but an innovation, either by the disciples, or by Paul.

Whether we view Jesus as ultimately right wing or left wing on this issue, it is clear that the tension between the Jewish left and Jewish right existed prior to the coming of Jesus. Jesus’s teachings, which seemed to question the established religious authorities and allow for some leniency or flexibility in the application or interpretation of the law (hanging out with prostitutes and tax collectors, performing miracles on the Sabbath, overturning the tables of the money changers) opened the door to a synthesis between Hellenism and Judaism.

Without Christ as the superordinate principle, God in the flesh, the paradox of this clash of cultures could not be resolved. In this sense, Jesus was not a conspiracy to subjugate the gentiles, but rather, to reconcile and bring peace to a greatly disturbed Jewish nation. By “giving unto Caesar that which is Caesars,” and relaxing the law, Jesus gave the Jewish people a new figure to place their hope in. Again, to make reference to a modern phenomenon, we can see the way in which the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II took the wind out of the sails of German nationalism. It was only by introducing a new cult of Hitler that German nationalism was able to fully revive.

The personality cult of Jesus, which elevated him to Godhood, was not entirely unique in history. Instead of viewing Jesus as a made-up character, comparing him to Zeus or Odin, it is more likely that even Zeus or Odin were, at some point, real historical characters, who were later only mythologized and theologized.

Christianity can be best understood as a form of identity therapy for a lost and confused people. Jesus gave the Jewish people a miraculous means of resolving their own internal conflicts over ethnic identity, inter-ethnic marriages, their love of Platonism and philosophy broadly, as well as the uncomfortable position of being dominated and subjugated by a foreign people. Jesus accomplished these tasks in the most efficient manner possible, by soothing and assuaging the Jewish cultural tradition (coming in the line of David, fulfilling their prophecies) while also allowing for a catharsis from the run-away trend of legalistic extremism (not one iota of the law shall pass away, but in Christ there is forgiveness).

Jesus Christ is the ultimate medicine for an extremely neurotic and self-hating people. When the psychological tension became too great, Jesus came to heal the spiritual pain that cried out for a savior. This explanation could co-exist with a Christian’s belief in Jesus’s divinity, but it could also co-exist with those who believe Jesus did not even exist. In either case, the mythology of Jesus fits perfectly into the psychological needs of the Jews at that time.

Of course, not all Jews converted to Christianity, since some took a right-wing path of adhering more strictly to tradition. Ultimately, the Jews who remained in Palestine dwindled in number, and Judaism only survived in large or influential numbers in other territories. The Sephardic Jews of Spain, once they came under Muslim rule, found Islam to be an extremely friendly force. The Jews of the middle east, instead of being most prominent in Palestine, came to direct much of the trade and commerce in Baghdad. In this respect, they were not altogether different from the Christians of the Muslim world, who also were overrepresented in various aspects of the economy.

Jesus’s teachings, as represented by Paul, extend the olive branch which Jesus brought to the Jews and extends it to the whole world. Any people facing an extreme crisis of authority or identity — whether political or religious — can see the appeal of the message of reconciliation, forgiveness, and the Hegelian synthesis implicit in the trinity. The Father (tradition) condemns us to death for breaking the law (inter-ethnic marriage, for example), but the son comes to redeem us, and the Holy Spirit guides us.

Christianity is a remarkable simple religion, and its close relationship with Hellenism meant that anywhere that Greek influence could be found, there was fertile soil for Christianity. The Germans of Europe were experiencing an identity crisis of their own, not unlike the Jews. In the case of Germanic Europe, they were experiencing a massive cultural shift as Roman clothing, ideas, language, and culture flooded into northern Europe.

The archaeological evidence is clear that Roman coins can be found all over Germany. Furthermore, the historical evidence shows that Germans were kidnapped, taken to Rome, and eventually reintegrated into German society. Such events clearly made a great impression on German culture. The great Arminius, the national hero of his time, was such a “hostage” of the Romans.

This irony is typical of many national movements. The Japanese industrial period of the 19th century was both an emulation of the west, but also a rejection of western colonization and an assertion of Japanese sovereignty. Similarly, Arminius, the symbol of German independence from Rome, also brought to Germany many Roman concepts — the concept of the unity of a people, for example, which was foreign to the Germanic tribes. Before the threat of the Romans, the Germanic tribes never needed to unite as one against a foreign foe. The Celts and Slavs were tribal themselves. But the Roman empire, through its conflict with Germany, forced the Germans to consider themselves as something more than tribalists.

The shift from tribalism to nationalism created a great deal of psychological uncertainty for the Germans. Just as Arminius could be considered a right-wing German, opposing Roman influence, there was also a current of the left among the Germans who sought to Romanize themselves. It was under these conditions that many Germans began to find Christianity appealing, as a symbol of Roman culture. Like the Romans who “Romanized” Christianity, the Germans also “Germanized” it.

Today, Christianity, to the extent that it exists at all, has been extremely “Americanized” or “liberalized.” Christianity is either a symbol of Zionism, Islamophobia, and seed oils, or it is subjugated leftism as a junior partner. Yet despite the degradation of Christianity, which occurred due to philosophical2 and scientific revolutions, the original psychological need which Christianity fulfilled has not disappeared.

People are still confused between left and right. White people especially feel that they have no culture. Some white people have taken to worshipping Hitler, as the symbol of a God who died at the hands of Jewish persecution. Others have attempted to forge a new identity in transhumanism, transexualism, or even transracialism. Some of them are becoming traditionalist Catholics or converting to Orthodoxy.

The baptism symbolizes one who has be submerged in the Atlantean flood, but who re-emerges and is reborn. When the solid land of tradition, authority, and normalcy begins to be swallowed up by the oceans, it seems as if the world is ending, as in the days of Noah. It seems that the apocalypse is coming. But there is an ark, a hope, which provides from on high an encouraging voice. It can only be a selfless love who would take pity on those who are drowning. The picture of Jesus in the storm, who grabs the drowning and pulls them up, this is the image which was so powerful to the lost and hopeless Jews of the 1st century.

Unlike Spengler, who viewed the duty of the Roman soldier to stand firm as he is enveloped by lava, the Christian believes that salvation is always possible, even in the worst of circumstances. This attitude is uniquely powerful, and this, as much as anything else, is a large part of the success of Christianity, in all its various forms.

Ironically, it is Christianity today which represents the “old authority” which is now uncertain. Blasphemy is common, the Bible is outdated, science has disproven it, and its adherents no longer are willing to die for it. For most of them, saying that Jesus is burning in hell is a lesser offense than the n-word, or some other politically correct notion.

In order for Christianity to renew itself, it must have new wineskins for new wine. In that sense, merely returning to the old order is not possible. Leftism is such an attempt — Christianity without Christ. Yet leftism, in its drive for equality and universality, is producing a backlash. In this sense, leftism can be seen as the new Rome, and the backlash as the Germanic tribes. The story ends with leftism becoming so corrupt, so bloated, so over-confident and sclerotic and weak that the Germanic tribes finally invade and put an end to it. The centuries which follow may be quite dark, but history does not end there.

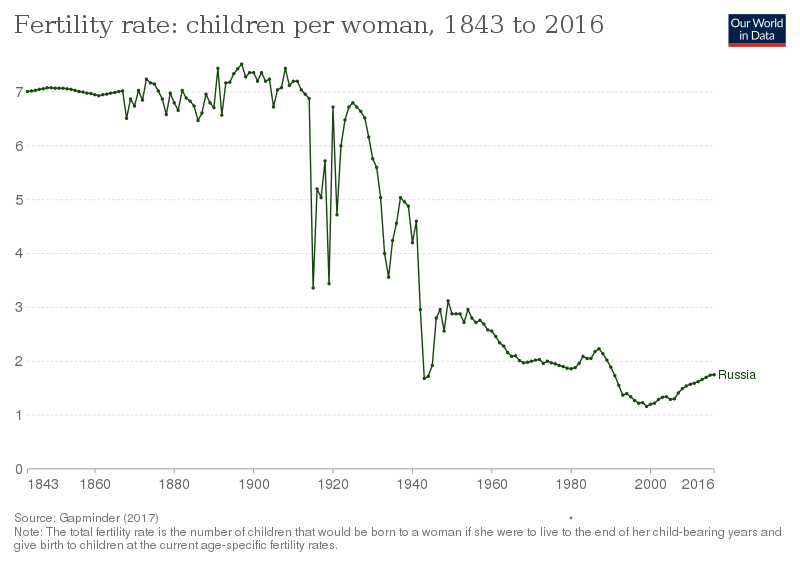

Spengler suggested that Russia would represent the new vital force. Spengler wrote that when Russians still had a birthrate which was one of the highest in the world — 6 or 7 children per woman prior to 1918, when Spengler published Der Untergang. Russian birthrates did not experience an unprecedented decline until 1940, and by 1960 it was clear that Russia did not maintain the biological vitality which Spengler had projected.

Another candidate for the “Germanics” of our era would be the Chinese, who represent a rising power in comparison with America’s declining power. But the Chinese have even worse demographic problems than America, and are completely neurotically over-civilized. They are not the “barbarians” that Spengler envisioned.

Neither, by the way, are the Mexicans. Mexico has an average fertility of 1.8 births per woman. Even in Saudi Arabia, the ultimate symbol of Islamic theocracy, the birthrate is only 2.2, and dropping. In South Africa, the birthrate is only 2.4. In the rest of Africa, it is following this trend.

No — biological vitality is not increasing or even remaining steadily in a single corner of the globe. There exists no uncontacted tribe or hyperborean race waiting in the shadows for its time to strike. A biological model of barbarism, such as Spengler proposed, is not to be found.

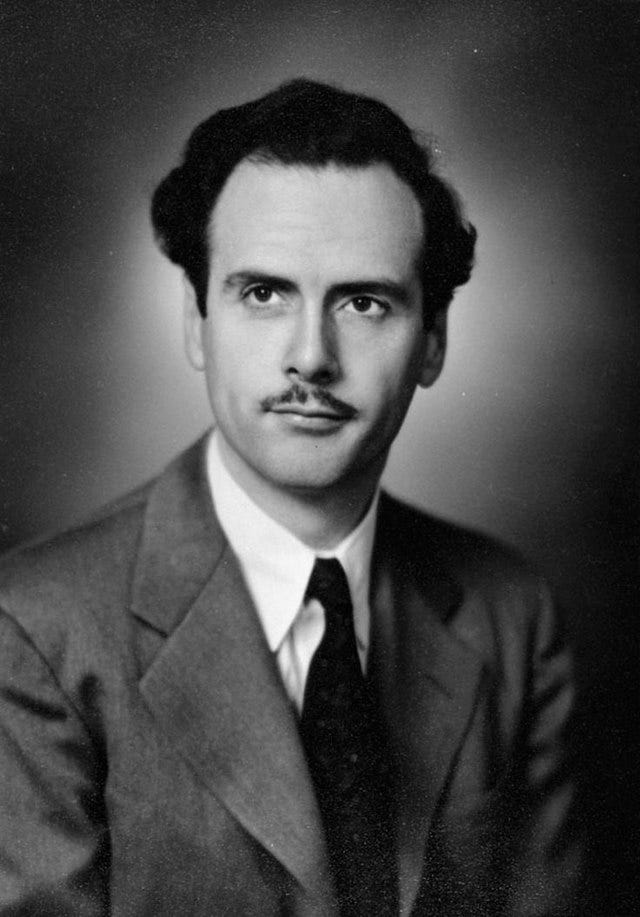

Instead, a technological model, following McLuhan, allows for a vision of the future. Social media, with all its vitriol, hatred, and violence, is the new barbaric vitalism. It might seem unreal, or like LARPing, or a bunch of keyboard warriors, but just as the Germans slowly infiltrated the Roman army, so social media is slowly creeping into our society. Its influence is pernicious, malevolent, and caustic, but nothing is stopping its advance.

On top of this, AI and the ability to generate realistic videos of anything imaginable create a perfect storm. Either technology must be halted by force — which will only create more psychological pressure for the eventual release — or it will inevitably explode in a new Sack of Rome. This is Pandora’s Box, and we have opened it.

The point of such a time is not to survive, to escape, or to preserve the existing culture. Rome could not have accomplished that with better scheming or more economical planning. In fact, the sooner that the end occurs, the sooner that the remaining Romans can begin the work of rebuilding their country under Germanic rule. Eventually, out of the ashes of Rome, Italy emerged once again, and the Renaissance showed the spirit of the phoenix.

This could be called “accelerationism,” but it has nothing to do with a worsening of material conditions. The Romans were not “shocked” into remembering themselves. Nothing could stimulate them or remind them of their past. Instead, they had to be physically defeated, and their empire smashed, in order for a new ethnogenesis to take place.

Most accelerationism posits that the example of South Africa, if it were brought to North America, would inspire radical political change. But again, the crisis at hand is not one of diminishing technical prowess, but one of the degradation of internal authority and confidence. People no longer believe in the legitimacy of the system. But, since there is no alternative, they remain passive and wait for the end to come.

No system can persist which does not hold itself as sacred. The Soviet Union fell, not because its weapons failed, but because the will of its leaders, to repeat the actions of 1956, failed. The same hollowness which infected the Soviets now infects the west.

That this is everywhere recognized does not mean the west will fall next year. On the contrary, we have not even obtained our Julius Caesar, who will inject new life into the system for perhaps centuries more.

Like the Pharisees, some will cling to their culture and not give it up, and may survive for thousands of years like this. Ultimately, the rareness of the Jewish survival owes to the particularity of that religion, its authority structure, its myths, and its esoteric components. It was always the Jewish priest class which kept the religion alive — not the warrior class, or even its merchants. Those who neglect the study of history, philosophy, and metaphysics cannot hope to emulate the Jewish strategy for survival.

This is true even if Schopenhauer hated Hegel — in opposing Hegel, or responding to him, he was in many ways reacting to the same cultural and intellectual forces which created Hegel.

12th century nominalism, William of Ockham.