English history can be viewed as a series of binary ethnic conflicts. Although each of these "binaries" intersected, overlapped, and produced three-way or multi-directional conflicts, it is useful to examine each of them individually in their simplest, binary form.

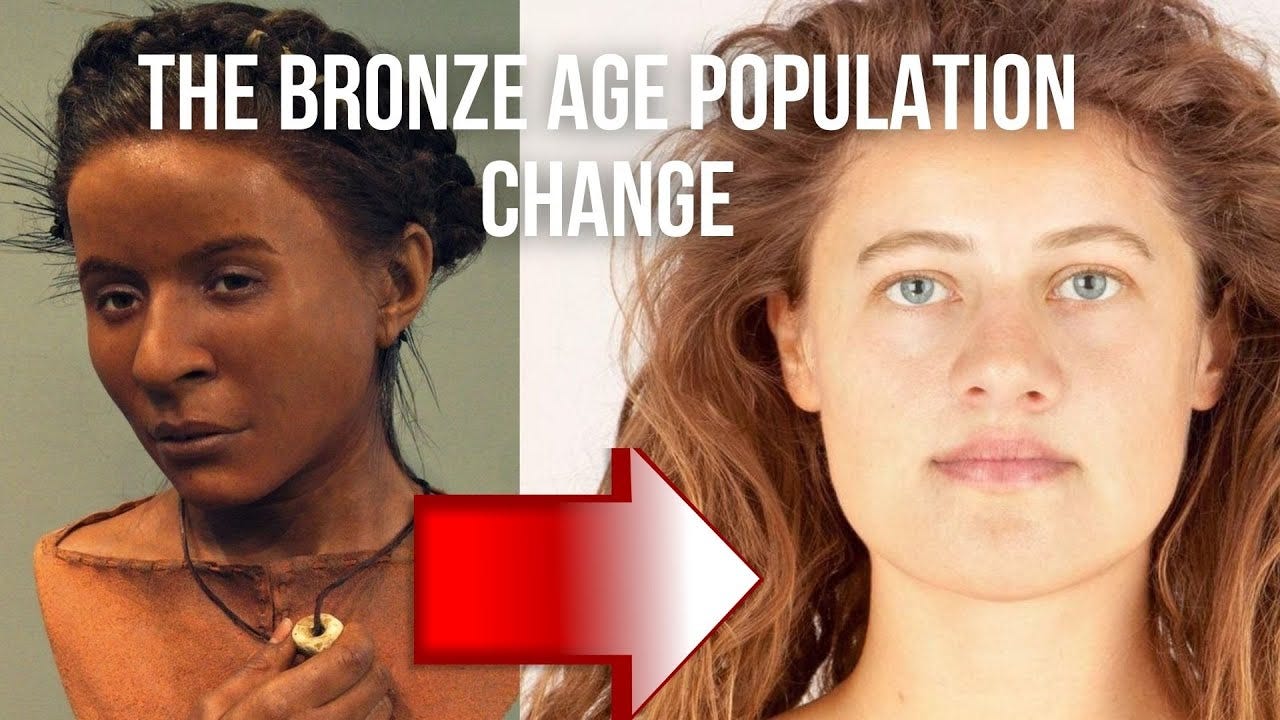

#1: Anatolians invaded by Yamnaya: 2500 BC

1. The first conflict was the Yamnaya invasion. It was a conflict between the Neolithic Anatolian-descended British and the Indo-European invaders of 2500 BC. It was resolved with a genocide and replacement of 90% of the Neolithic population, likely occurring over a relatively short period of a few hundred years.

#2: Yamnaya invaded by Celts: 1300 BC

2. The next conflict was the Celtic Invasion. It was between the Bell Beakers and the Celtic invaders, between 1300 BC and 800 BC. It was resolved with the domination of Celtic languages in all British isles within a 500 year period.

#3: Celts invaded by Romans: 55 BC

The third conflict was the Celtic vs Roman conflict. It was between Celtic natives and Romans beginning in 55 BC. The defeated Celts of the south, including the Welsh, became Christianized and Romanized, and were opposed by the Scottish Picts who remained pagan and “barbaric.”

#4: Romans invaded by Picts and Irish: 354 AD

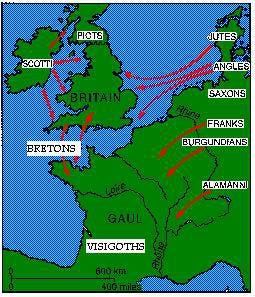

When the Roman empire abandoned Britain, the Britons came under heavy attack from the Picts of the north and the Irish of the west, as well as the Saxons of the east. Gildas the wise writes1 that the Britons made a final appeal for Roman aid called “the groans of the Britons” (gemitus Britannorum), sent as late as 454:

"To Agitius [or Aetius], thrice consul: the groans of the Britons. [...] The barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea drives us to the barbarians; between these two means of death, we are either killed or drowned."2

While the Picts are thought of today as “Scottish,” the term “Scotti,” at the time, referred to Gaelic tribes from Ireland. It was the English who associated all Gaelic languages with Ireland, and therefore referred to the Gaelic tribes north of England as “Scottish,” which was their way of saying, “the tribes north of us are of Irish origin.” While this was not exactly true, it is interesting to note that the ethnonym “Scottish” originally meant “Irish.”

#5: Romanized Celts invaded by North Sea Germans: 537 AD

In response to the viciousness of the Picts and Irish, the Britons were said to have hired Anglo-Saxon mercenaries, who, while not Christian, seemed preferable to other barbarians. Saxons had a long history of raiding Britain, beginning in 230 with the construction of Fort Branodunum as part of the "Saxon Shore" defensive line.

However, after allying with the Welsh, the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries were so successful in repelling both Irish and Picts that they came to dominate Britain and drive the Welsh and Cornish to the western fringes of the island. The victory of the Anglo-Saxons over the Celts, represented by the mythological death of King Arthur in 537, ended the identity of Romanitas among the Celts.

The ethnic conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Celts did not end with the death of Arthur. Welsh and Scottish Gaelic national identity continued to flare up, causing rebellions through the 15th century. If the Irish-English conflict is considered a subset of the larger Celtic-English conflict, then it can be said to have continued as recently as 2001, when 16 deaths were attributed to the "Irish Troubles.” The British peacekeeping operation, Operation Banner, ended in 2007. Thus, the Celtic-Germanic conflict is the longest in British history, lasting 1700 years.

#6: English invaded by Northmen

This brings us, at last, to the Nordic War. The Nordic War is typically referred to as the “Viking Age,” however the term Viking is almost entirely fictional and ahistorical, with a few exceptions. Raiders during the 9th century did not refer to themselves as Vikings. They referred to themselves as Danes, Northmen, or Eastmen. The English referred to them as Heathens and Pagans.

The Scandinavian expansion did not begin in the 9th century, however. The Anglo-Saxon invasion of England must be understood as a consequence of the Scandinavian or Danish expansion into Jutland, as early as the 2nd century. The inhabitants of Jutland included Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, who were pushed out by Scandinavian or Danish incursions. Like the Trojans who landed in Italy, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes ended up invading Britain. Nennius, who wrote the Historia Brittonum (828), claimed that Britain itself was settled by Trojans, and this claim may derive from the fact that the Anglo-Saxons were very much like the Trojans as depicted in the Aeneid: warrior refugees.

From the 5th century to the 7th century, pagan Anglo-Saxons continued to migrate from Jutland and the Frisian coast into Britain. By 731, migration had largely ceased, and England was made entirely Christian. For 62 years after Bede wrote his ecclesiastical history, Britain was allowed to consolidate its Anglo-Saxon Christian identity.

However, this respite was brief. Danish presence in Cornwall is recorded as early as 787, only 56 years after Bede’s triumphal history. The attack on Lindisfarne in 793 was, therefore, entirely in-line with centuries of Scandinavian expansion toward the west, especially by naval attack.

"In the year 834, a [Norse] war-band crossed the Channel and launched a plundering raid [..]. This raid appears to have been the first significant action in the region for four decades, and marked the beginning of what was to be an almost annual experience. [..] Anglo-Saxon sources almost uniformly label these western raiders 'Danes' or, more generically, 'heathens', [but] it is possible that they were Norwegian and part of the steadily increasing northern Scandinavian presence in western maritime Britain."3

The Danes raided Sheppey in 835, off the coast of Kent. In 838, the Danish-Cornish alliance was defeated by Ecgberght of Wessex. However, Danish raids continued in the south and east in 841, reaching London in 842. In 851, in the first naval battle in English history, the Danes were repelled by the Kentish navy. Rather than giving up, the Danes colonized the Isle of Thanet off the coast of Kent.4 This was the first Scandinavian settlement in England, although in Ireland, Dublin had already been colonized by the Norse in 841.

In the period between 851 and 864, the Kingdom of the Franks was better equipped to defend itself against raiders. As a result, Norse commanders such as Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan assembled what the Anglo-Saxons called the micel here.5

"Speed and mobility had been the keys to the [Norse] successful sea-borne raiding since the late eighth century. Their highly manoeuvrable ships enabled them to land, strike and withdraw with tremendous rapidity. Now they were transferring those same skills to land-based fighting. The source of their mobility was horses [..]. On horseback, Ivar and Halfdan's Danes literally left the Anglo-Saxon infantry warriors standing."6

The Great Army took advantage of a civil war in Northumbria to conquer a divided land. During this period, Old Norse influenced the English language. An examination of Norse words in the English language will help us understand the cultural differences between Anglo-Saxons and the Norwegian-Danes:

Emotion:

Anger, awe, berserk, craze, scare.

Criticism and Insults:

Dastard, flaw, blunder, fluster, harsh, irk, lag, mistake, niggard, odd, outlaw, ragtag, scant, wrong.

Physical Inferiority:

Chubby, clumsy, flounder, skittish, lemming, meek, oaf, scrawny, shrimp (a small man), weak, stumble.

Loud or Rude Communication:

Call, gab, wail, squabble, wheeze, scoff, scold, grovel, nag, snub, blather.

Rude Postures or Facial Expressions:

Gawk, scowl, slouch, slump, shrug.

Disgusting or Gross:

Dirt, dreg, gag, rag, ragged, rotten, rugged, scraggly, trash, ugly, tatter, scrap, fleck, shrivel.

Success, Wealth, Bragging, and Power:

Bloom, boast, boon, cozy, flaunt, gift, give, glitter, gloat, guest, haggle, happy, husband (master of a house), law, skill, thrive.

Merchandise and Economy:

Wicker (a basket), window, gear, lathe, smithy, plough, loan, sale, scale, score (the number 20), kilt, skirt, rug, scarf.

Nautical and Geographical:

Bank (as in a river bank), brink (of a cliff), creek, gale, geyser, hank (on a sail), haven, keel, mire, muck, raft, reef, rig, skip (as in skipper), stern (cognate with steer), flag.

Weather:

Dank, fog, gust, muggy, sky, slush, squall

Intelligence:

Sleuth, sly, wile (as in wily), thrift.

Violence, Theft, and War:

Bash, brunt, bump, burst, clip, club, cut, dash, daze, die, fling, gang, gun (originally meaning war), hit, kick, kidnap, wreck, knife, nab, ransack, rid, rift, scathe, scuff, skeet (to shoot), skewer, skid, slam, slaughter, sling, snag, snare, spike, stagger, thrust, thwart, take, scrape, get.

Neutral Bodily Verbs:

Cast (as in fishing), dangle, doze, droop, dump, flit, gait, hug, lift, lope, lug, nudge, prod, race (to run), sprint.

Pain or Sickness:

Blister, gasp, gaunt, haunt, ill, queasy.

Movement:

Sway, whisk, wag, toss, tag, tether.

Body and Physiology:

Birth, crawl, crotch, crouch, freckle, leg, rump, scalp, skin, skull.

Food and Animals:

Brisket, bull, egg, filly, geld, keg, kid (a goat), mug, steak.

Misc.:

Bulk, fellow, gap, gape, girth, kindle, lad, lass, loft, low, root, scorch, slant, sledge (hammer), tangle.

Danes or Northmen were clearly emotionally volatile; they also had an extremely judgmental physical culture which would ruthlessly bully anyone who was physically uncoordinated, small, or weak; the number of words they have for “bad communication” indicates that they preferred silence and stoicism over excessive “blather”; their words for filth indicate that they placed a high premium on cleanliness; their words such as “loan, sale, scale” indicate that they had to be good salesmen of the items they pillaged at other markets; their words for intelligence show a strong tendency toward cleverness, both in terms of deception as well as uncovering deception; their words for food indicate that they enjoyed steak, brisket, eggs, and a keg of alcohol.

The physical culture of the Scandinavians was profound and specific. The Norse had terms for every kind of posture, position, stance, and physical demeanor which assimilated into English. Emotionally, we could say that they were repressed, allowing for the unleashing of extreme rage in battle. The Norse tendency to hyper-fixate on things which were dirty may come from the fact that as warriors, cleanliness was necessary to prevent infection of wounds.

All of these qualities — physical, emotional, and bodily — were a part of the Norse success in establishing the Danelaw. Unlike the Anglo-Saxons, who were driven entirely as a population out of Jutland, the Norse raided England as a warrior elite. As such, the Norse contribution to British population genetics is smaller, between 3% to 16%.

The Norse conquest of the Danelaw was not isolated. The Norse also settled in Normandy, Iceland, Greenland, and established themselves as the first princes of Rus. In Greenland, the small native population still retains much of its original ancestry: only 25% of Greenlandic ancestry is from Europe. In Iceland, there was no native population, but Norse colonists took Scottish and Irish wives with them, so Iceland has a mixed ancestry of Norse and Celtic origin. In Russia, estimates by Haplogroup I indicate a Norse ancestry of 17%. However, with Haplogroups, this determines patrilineal descent, not total ancestral composition.7 Still, according to Haplogroup I, medieval England had almost twice this frequency of Haplogroup I, around 30%.

The modern frequency of Haplogroup I in Britain tends to be in east Anglia (around 25%), while it is lowest in Wales. Haplogroup R1a, closely associated with Norway, does not appear very frequently outside the far north of Scotland or the Isle of Man.

When compared with Germany specifically, there is a “similarity of populations from Britain and Peninsular Scandinavia, and [..] closer Scandinavian affiliation of the Danelaw compared to the non-Danelaw subdivision of Britain.”8 This analysis was done by examining the presence of R1a1 within Britain, originating from a “male-specific contribution.” In other words, Norse immigrants did not bring their women with them, and fathered children with Anglo-Saxon women.

Norse immigration into Britain began in earnest in 865 and continued with the Norman conquest of 1066. However, the army of William the Conqueror was only around 10,000 strong, compared to a total population of over 1 million British. Roughly 3% of those would have been Anglo-Saxon nobles, or 30,000. Since the Normans did not practice strict endogamy, and married into the Anglo-Saxon nobility, it is probable that the resulting nobility would be of less than 25% Norman origin.

Therefore, the vast majority of Norse ancestry in England would have been introduced before the Norman conquest of 1066, confining the majority of this influence to a period of 199 years beginning in 865. This is ironic in the following sense: the era of the greatest reproductive success was the pre-Norman era, but the era of total Norse political victory came after 1066. One must also recognize that culturally, the Normans had recently and suddenly abandoned the Norse language and become conversant in French.

In the next article, we will cover the threats to the Danelaw, including additional Scandinavian invasions, up until the Norman conquest.

De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, c. 520 AD).

John Allen Giles, “The Works of Gildas, Surnamed 'Sapiens,' or the Wise,” in Six Old English Chronicles, of Which Two Are Now First Translated from the Monkish Latin Originals (1848). Revision of the translation of Thomas Habington, The Epistle of Gildas the most ancient British Author: who flourished in the yeere of our Lord, 546. And who by his great erudition, sanctitie, and wisdome, acquired the name of Sapiens. Faithfully translated out of the originall Latine (1638).

Angelo Forte, Richard Oram, and Frederik Pederson. Viking Empires, 2005. Page 66.

It was once an island, but the Wantsum Channel was eroded by 1540. However, during the North Sea flood of 1953, the Isle briefly became an island once again.

Mikel is cognate with mega, and here with the German Heer.

Viking Empires, page 69.

A person could be ethnically African, but have a European haplogroup if his great great grandfather was European.

"Subdividing Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a1 reveals Norse Viking dispersal lineages in Britain." 2020.

The Norse didn't settle Greenland, really. It was and is unarable, unherdable and thus unsuitable for a culture like theirs. And just like in Iceland, there was no native population at the time either. I recall the Inuit arrived around 14th century or so, and they gained their Nordic (Danish) admixture only very recently, just like it says in the abstract of the paper you link to. (Greenland is an autonomous part of Denmark.)

Nice article could throw in the recent migrants as a new invasion lol