Only one country ever defeated the Soviet Union in war.1 That country was Finland. With a population of 3.7 million, the Finns conscripted 700k soldiers, or 18.9% of their population. In addition, the Germans supplied Finland with 250k additional auxiliary troops. During the Continuation War, Finland imposed between 890k to 944k military casualties on the Soviets, after which point the Soviets gave up, ignored Finland, made a separate peace, and concentrated on Germany.

Stalin wanted to conquer Finland in order to turn it into another Soviet Socialist Republic. However, the number of Soviet troops who died trying to defeat Finland was equal to 25% of Finland’s total population. Or, in other terms, the number of Soviet military casualties was equal to the size of the Axis armies in Finland. For Stalin, the juice was not worth the squeeze.

Germany, by contrast, had a population of 70 million. Using the Finnish ratio, Stalin should have simply given up once Soviet casualties exceeded 25% of Germany’s population — 17.5 million. Or, alternatively, once Soviet casualties exceeded the total number of German troops — 13.6 million.

Around 8.7 Soviet soldiers were killed in the war. For reference, total casualties (including wounded and sick) are generally three to four times larger than the death count. In 1945, when losses were undercounted due to statistical incompetence and propaganda, the Soviets admitted that 13.9 million soldiers were wounded.2 Since then, Grigori Krivosheev estimates that over 22 million Soviet soldiers were wounded or sick during the war.3 This gives a total of 31 million Soviet military casualties.

Assuming that the Soviets could only conscript up to 20% of their population, the maximum number of Soviet soldiers which could have been fielded in battle was 37 million. Accordingly, 84% of the total Soviet military potential was destroyed between 1941 and 1945.

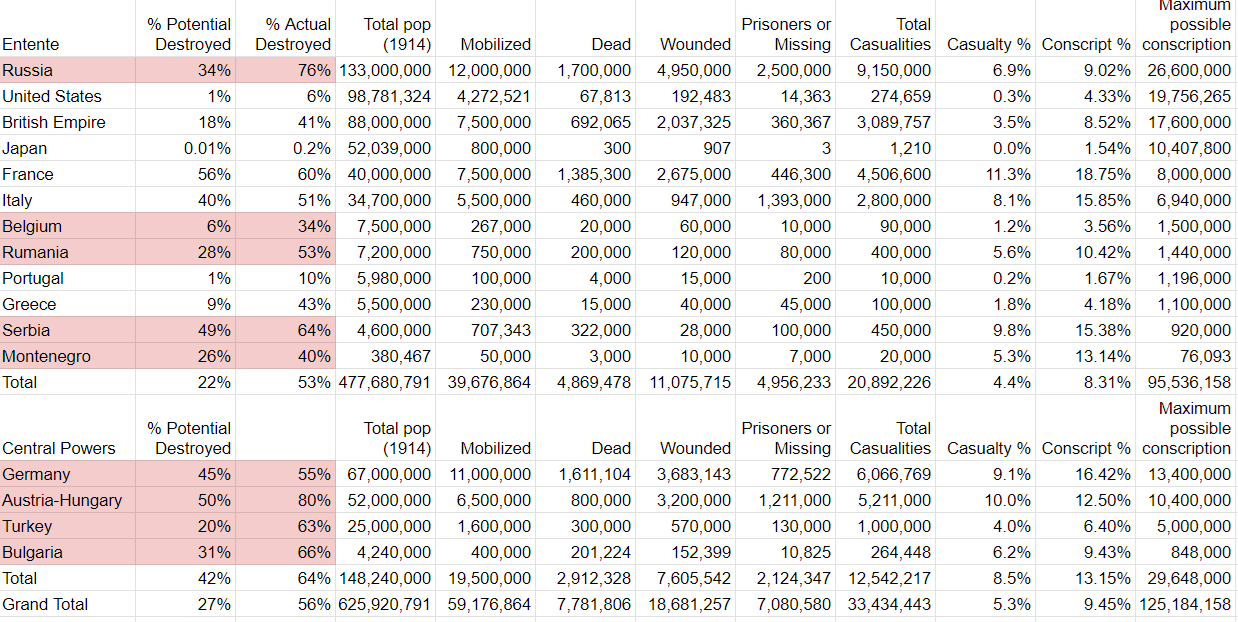

During WWI, Russia mobilized 12 million troops, out of a population of between 133 and 159 million. This wide discrepancy exists because the Russian Empire did not take any reliable census for 17 years. As a result, the Russians mobilized between 8 to 9% of their population.

The following data is largely from the Library of Congress:

During WWI, 9% of Russia was conscripted, 16% of Germany, 19% of France, and 15% of Italy. Of the actually conscripted forces, 76% of Russia’s military strength was destroyed, 60% of France, 55% of Germany, 80% of Austria-Hungary, and 63% of Turkey. The Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman forces were both on the brink of collapse by the end of the war.

For Germany to destroy 84% of the Soviet military capacity indicates that the Soviet military should have been on the brink of collapse in 1945. Both General Patton and Winston Churchill believed that the American army, with 16 million soldiers in reserve, could certainly destroyed the remnants of the Soviet army, which could only summon 6 million soldiers in total.

The principal difference between the Russian collapse in WWI and the Russian success in WWII is that, despite losing a greater percentage of its conscripted soldiers, the Russian army was better equipped. This was largely due to Lend-Lease.

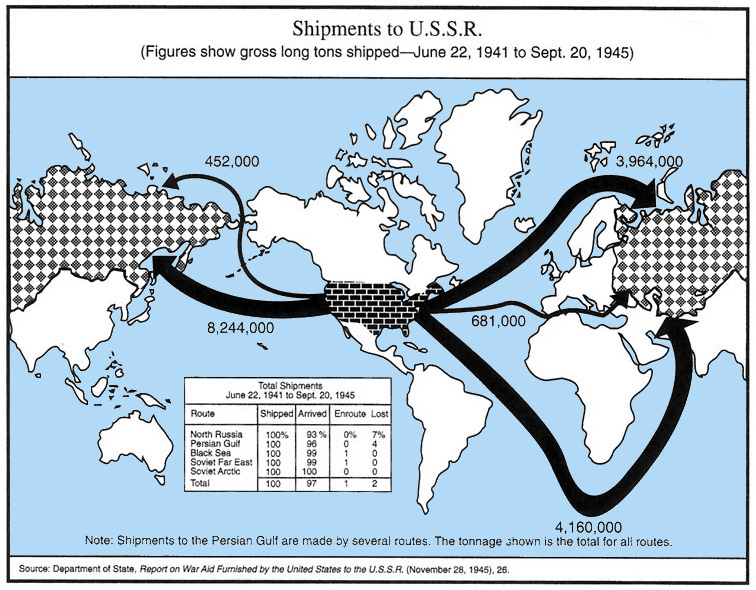

Lend-Lease was a program of material assistance from the United States to Britain and Russia, and also from Britain to Russia.

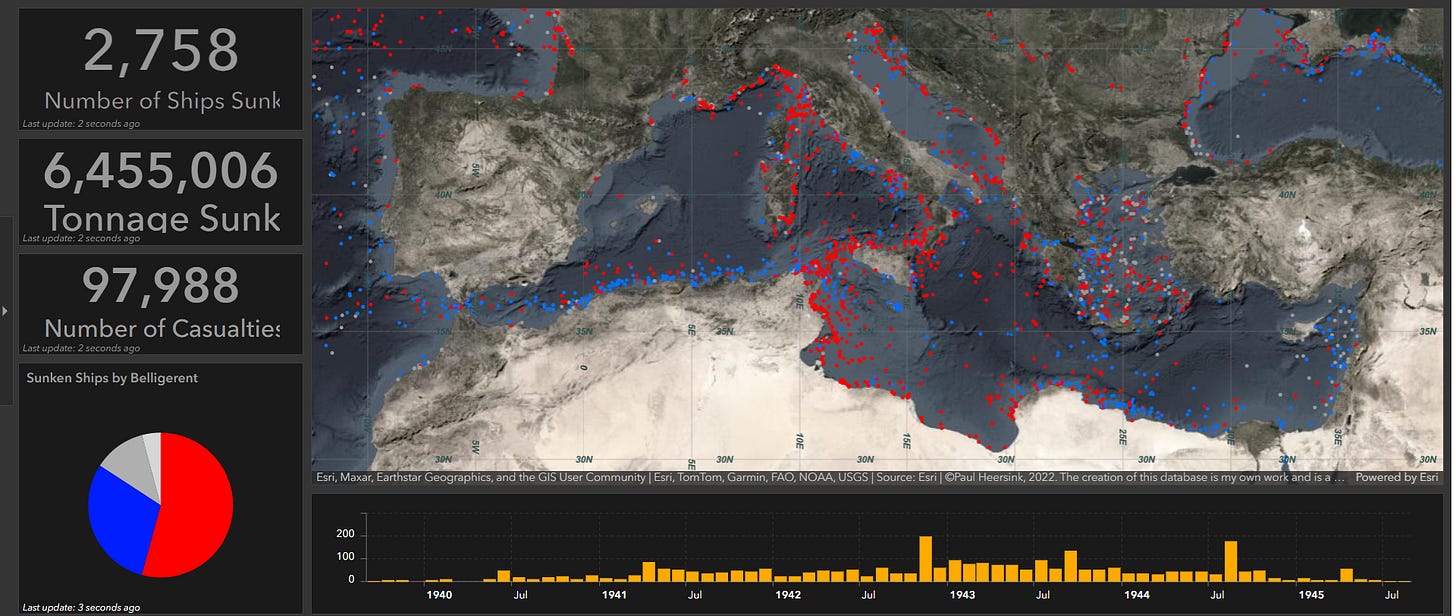

92% of Russian trains were produced by Lend-Lease: 1,911 locomotives and 11,225 railcars. 18,200 aircraft, about 30% of the Soviet air force, was provided by Lend-Lease. Lend-Lease provided 400,000 jeeps and trucks, which was 30% of Soviet vehicles, mostly Dodge and Studebaker.4 Only 8% of Soviet tanks were provided by Lend-Lease, but in light of the fact that the Soviet military was 16% away from total destruction, every 8% counts.5

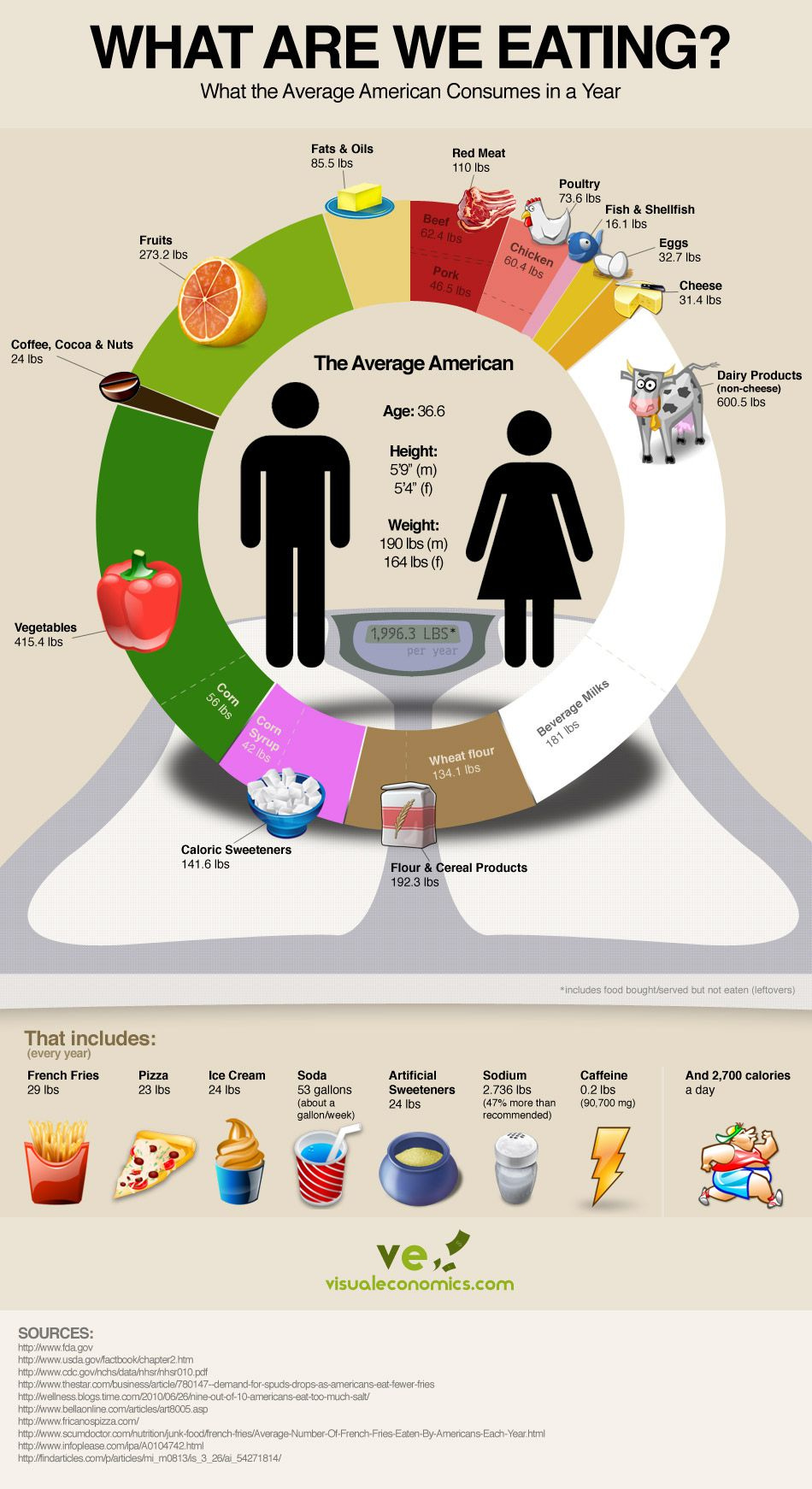

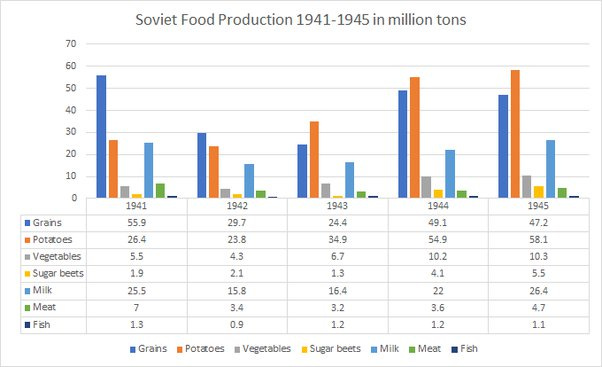

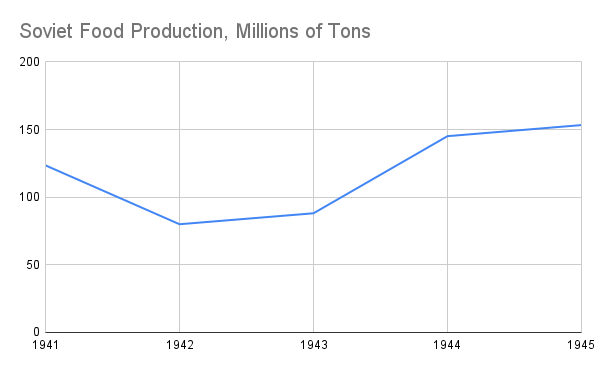

Lend-Lease also delivered between 1.75 to 5 million tons of food,6 representing at most 6% of Soviet food production. Americans eat on average one ton of food per year, which is about 2700 calories. Despite food scarcity, Russian soldiers ate anywhere between 1500 and 4000 calories a day. Accordingly, Lend-Lease food deliveries saved between 1 million to 5 million Russians from dying of starvation.

Deprived of this food source, the Soviet Union would either have to use triage to eliminate some of the population from the rationing system (as was essentially done in Germany), or would have to subject the entire population to malnutrition, which would significantly decrease the efficacy of the average Soviet soldier.

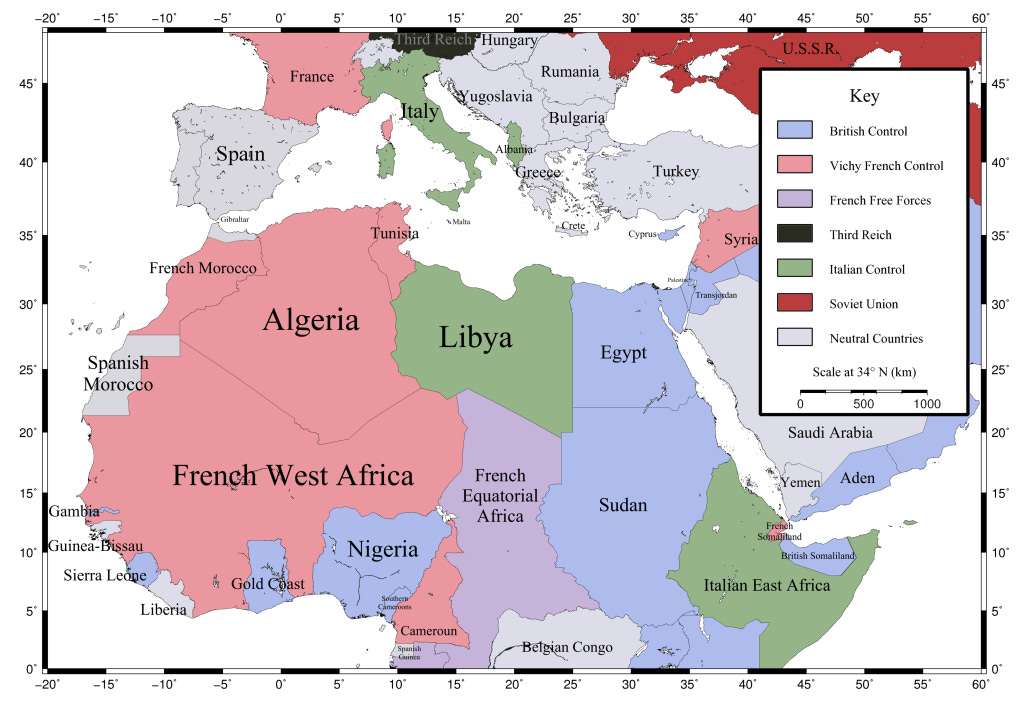

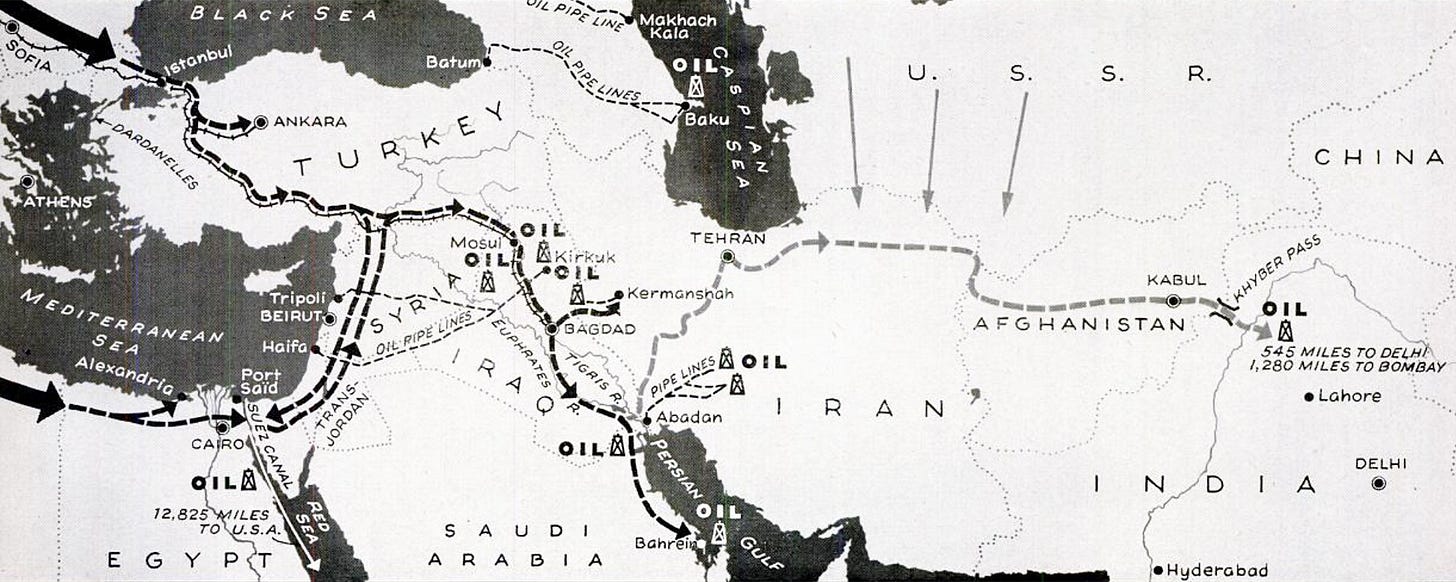

45% of Lend-Lease was sent through Iran.7 As a rough estimate, 13.5% of the Soviet air force, 13.5% of its vehicles, 41.4% of its trains, 3.6% of its tanks, and maybe 1-2% of Soviet food passed through Iran. At the bare minimum, 300,000 Soviet soldiers could not have been properly fielded or equipped without Lend-Lease. At most, without Lend-Lease 4 million Soviet soldiers would not have been able to participate in combat, either due to the loss of planes, transportation, or logistical capacity.

The important of railways for the Soviets has to do with the speed and maneuverability of their forces. As German forces became overextended at Stalingrad, for example, Soviet reinforcements were able to encircle and capture German army groups. Had the Soviets lacked the ability to transport troops quickly and efficiently, they would have been forced to mass their troops in defensive positions, and await German attack, or very slowly conduct their offensive. Counter-attacks and quick encirclements would have become impossible. The Germans could have more effectively retreated and avoided encirclement. This is crucial, because about 3 million German soldiers were captured by the Soviets, as compared with roughly 4 million who died in battle. Had the Russians lost 40% of their capacity for rapid movement, perhaps as many as 1 million German soldiers could have evaded capture.

Positional vs Material Strategy

The German approach toward the invasion of Russia has often been criticized on tactical grounds. For example, the argument that Germany should have ignored Stalingrad, and concentrated its forces on the capture of Moscow. Alternatively, the view that Germany should have ignored Moscow, and concentrated its forces on Stalingrad. Both Stalingrad and Moscow were major transportation hubs, and the capture of either one would have debilitated the Soviet railway network.

These differences of opinion can be classified as disagreements on positional strategy. Germany invaded Russia — which cities should it target? What should be the specific geography of the front lines? What should be the distribution of military forces in the north, center, and south?

Positional strategy is important, but it is difficult to determine with hard numbers what the differing effect of a counterfactual would be. Had the Germans massed additional resources against Moscow, would the Soviets simply redirected their forces to defend Moscow? And had the Germans ignored Moscow in favor of Stalingrad, would the Soviets not also reinforce Stalingrad to the same degree?

The question put forward here is not whether the Germans could have taken Moscow or Stalingrad. Had that occurred, as almost occurred with Leningrad, the Soviets could have retreated even further into defensive positions. The problem for the Germans is that, after 1941, their oil reserves were dwindling, as Romanian production could not keep up with German demand. Without oil, the Germans could not drive tanks or fly planes.

A material strategy would necessitate that Germany trade the lives of its soldiers for additional resources, at the expense of the enemy. Was this possible? Could Germany have dedicated additional soldiers to its attack on Russia, either in 1941 or 1942?

The limiting factor on the deployment of soldiers at this stage in the war was not the availability of soldiers in absolute terms, but rather, the ability to transport, deploy, and supply those soldiers. The supply lines which stretched from Berlin into Russia were long, and subject to sabotage. Russian partisans attacked German supply lines, and then disappeared into the forests. Russian roads were plagued with ice and mud. Even if Germany had more men available to send into Russia, they would not have been able to furnish these men with weapons, food, and other supplies. As it was, the German lack of winter clothes caused over 1 million soldiers to contract frostbite. The Germans were undersupplied for a long winter war with Russia. A German effort to build up logistical capacity in the lead up to invasion would have also been dangerous, since a conspicuous increase in winter coat production would have eliminated the element of surprise.

The question remains: how could Germany eliminate 6 million additional Russia soldiers, and entirely exhaust the Soviet military capacity? While positional strategy may have been able to marginally increase Russian casualties, the German-Russia casualty ratio was already extraordinarily high, with Germans often inflicting a 4:1 ratio upon the Russians. Overall, the German casualty ratio with Russia was even higher than Finland, which was one of the highest of any front of the war. Assuming that some positional errors were made, it is still difficult to imagine that changes in tactics could have allowed for millions of more Soviet troops to be destroyed.

Instead, by disrupting the flow of material goods into the Soviet Union, Germany had the ability to change its material strategy, and to deny the Soviets the ability to maneuver and supply their armies. Disruption could have only taken place in three locations:

The Pacific port at Vladivostok;

The Arctic route to Archangelsk;

The Persian route in Iran.

In the first case, due to the unwillingness of Japan to attack Vladivostok, the Pacific port was out of the reach of the German navy. Secondly, the Germans did make significant attempts to disrupt the arctic route. However, due to the breaking of the Enigma codes,8 German submarine positions were often known to the British, and they were able to evade naval attacks. While the Germans could attack individual British ships, they were not able to disable the sea lanes, by the means of mines or other tactics, because the range of routes was too wide and broad to be completely patrolled.

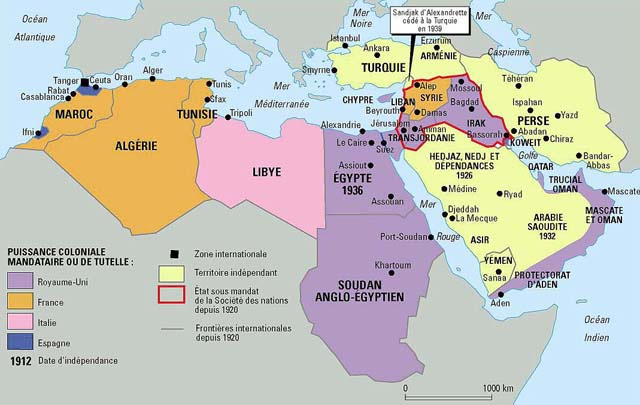

By contrast, the transportation of Lend-Lease material through Iran took place by railway. Even if the Germans were not able to occupy the entirety of Iran, if they could send saboteurs into Iran to disable to railways, similar to what Soviet partisans did to German supply lines, then they would be able to successfully slow the movement of goods. In order to achieve this proximity, the Germans would need to first conquer Iraq.

The failure of the German campaign in North Africa did not allow for a German advance into Iraq. How could this campaign have gone more successfully?

Operation Felix

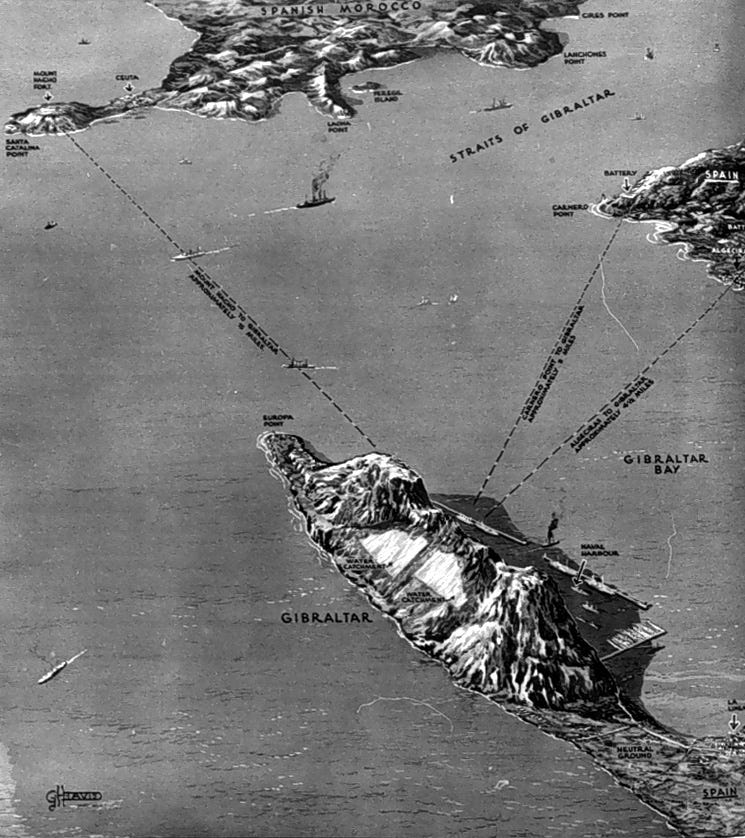

The straits of Gibraltar are a narrow 7 mile passage between Europe and Africa. The fort of Gibraltar, a British possession since the 18th century, effectively controlled which ships passed in and out of the Mediterranean. As a result, German and Italian troop transports originated mostly in Naples. The Italian navy, the fourth largest in the world after America, Britain, and Japan, was unable to operate outside of the Mediterranean due to this fort.

Operation Felix was a German plan to take Gibraltar. Franco pretended he was willing to join the war on the side of Germany. In fact, he was advised by the British agent who controlled German intelligence, Admiral Canaris, to delay and obfuscate so that Spain would remain neutral. Canaris was the most effective British spy during the war, and likely changed the outcome of the war.

Despite the fact that Canaris was actively directing the entire German intelligence effort in favor of the British, there were German generals who genuinely wanted to win the war. Heinz Guderian suggested that prior to the armistice with France on June 22, 1940, Germany should drive two divisions down into Spain to invade that country and take Gibraltar. The Spanish army was weak after three years of Civil War. Franco complained that his people barely had enough to eat. Given that it only took Germany 46 days to conquer Spain, it is not difficult to imagine that Spain could have been taken by August 25th.

It is clear in hindsight that aiding Franco during the Spanish Civil War was a strategic misstep for Germany. Franco accepted German aid willingly, but he never aligned himself with the idea of a German led Europe, and much preferred the British. Had Spain been an honest ally of the Germans, he would have revealed the attitude of Canaris as a traitor, and significantly changed the outcome of the war. Instead, he was committed to the path of conspiracy against the forces which saved Spanish Catholicism from social democracy. This is despite the fact that the British and American volunteers during the Spanish Civil War had directly fought against Franco.

Had Germany remained out of the Spanish Civil War, or even covertly worked against Franco, then the country would likely still be in a state of Civil War in 1940. A divided country, embroiled in chaos, would not be in a position to oppose a German invasion. Given that things did not go that way, it is still questionable as to whether Franco would fight to the last man against a German invasion. Like the Norwegians, Dutch, Belgians, and even the French, Franco would likely put up a symbolic resistance to a German invasion in order to guarantee his political favor among the British (who he hoped to win the war), but this would not necessarily be an exhaustive defense.

“If one looked at Spain as a whole, what did one see? Starving cities with industries at a standstill for want of imported raw materials.”9

The capture of Gibraltar would not have ended the war in the Mediterranean, and would have come at the cost of perhaps 100,000 German casualties. Furthermore, the British were already supplying Egypt through the Suez canal, not by Gibraltar. The capture of Gibraltar would not have increased British diesel consumption or reduced the British capacity to defend Egypt.

Eliminating Gibraltar as a British fort would however allow the Italian navy to escape from the Mediterranean, allowing it to harass British shipping along the Atlantic coast, and even engage in battles along the arctic passage. This would, of course, require that Italy see its military engagements in terms of the entire scope of the war, and not as actions limited to Italy’s selfish colonial aims in Africa. Given Mussolini’s track record of starting costly wars with non-belligerents to enlarge his ego, this was not likely.

The capture of Spain, however, would have had additional consequences:

The vulnerability of Portugal to conquest;

The ability for the Kriegsmarine to capture the Canaries and/or Azores to use as a base of operations against Atlantic shipping and transport;

The halting of Spanish trade with Britain, especially with regard to Tungsten, also known as Wolfram, as well as "Britain's crucial imports of iron ore and potash from Spain";

The establishment of a 7 mile corridor connecting Germany with North Africa.

Tungsten was crucial for producing armored tanks, as well as armor-piercing bullets. Denying the British access to Tungsten by ending Spain’s neutrality would have weakened Britain’s offensive and defensive capacity in the tank battles of North Africa. Tungsten was mined both in Spain and Portugal. By capturing these two countries, Germany could deny Britain access to this resource.

From the US Department of State archives:

Spain permitted a free market in the [tungsten] ore throughout the War, and the Allies’ greater access to hard currency gave them a significant advantage in the competition with Germany for Spanish wolfram. Before 1941, however, Germany had most of the advantages because it had begun developing Spanish wolfram sources at the end of the Spanish Civil War. [..] Germany created a network of Spanish front corporations, mostly owned by SOFINDUS, and by 1941 controlled the highest producing mine [..]. Germany acquired almost all the 700-1,000 tons of wolfram that Spain produced in 1941, while Britain, which first began preclusive buying in Spain in late 1941, purchased only 32 tons."

Because of Spain’s neutral status, Britain and America engaged in a trade war, and used cash reserves to try to deprive the Germans of tungsten:

In early 1942 Britain and the United States began a concerted preclusive buying program [.. which] increased [..] prices from about $75 per ton before the War to $16,800. [..] the Allies set up their own dummy corporation in October 1942 [..] purchasing almost 1,000 tons during the year. [..] In December 1942, [..] Spain pledged to deliver [..] wolfram, in exchange for German coal, armaments, fertilizers, chemicals, and manufactured items. [..] The agreement, however, soon collapsed, with both sides blaming the other for failing to make deliveries. Also in December Spain increased its minimum price of wolfram to about $20,500 per ton and allowed the Allies to exchange dollars and sterling for pesetas, giving them the means to purchase wolfram at a time when Germany’s peseta holdings were running low. During 1942 Germany also increased its efforts to acquire wolfram illegally. [..] The Allies estimated that the Germans smuggled almost 50 tons over the border per month by early 1943. In order further to limit this German supply of wolfram, the Allies bought a significant amount of wolfram on the Spanish black market.10

If the land-based attack on Spain was simultaneous with a naval attack on the Azores and Canaries, it would have been possible for Germany to extend the reach of its operations in the Atlantic, and sink more British ships, to further limit Britain’s ability to supply North Africa.

Finally, by capturing Gibraltar, German troop transports would have had a much safer route to North Africa. Without this, German troops were forced to travel longer distances from Sicily to Tunisia, which exposed them to the threat of the British Navy. With less naval resources spent on transporting German troops to North Africa, troop transport could have occurred faster and in a safer fashion.

It is unknowable if Franco would have put up a strong fight against Germany. Its army was weaker and worse supplied than the French. At the end of the Civil War, Franco’s army was about half the size of the French. After the Civil War was concluded, he reduced the size of the army in peacetime to 250k men, about a tenth of the French army. Franco claimed to have 2 million soldiers ready to take Gibraltar, but this was likely bluffing. Spanish mobilization never exceeded 750k during the war.11

Political factors were crucial to the fall of France. France fascist sympathies opened the door to diplomacy with Germany. In Spain, it is unknown if right wing elements such as the Falange would support a German invasion, or if they would remain loyal to Franco. Alternatively, it is unknown as to whether left wing elements in Spain, which were recently defeated by Franco, would rally to his side in the event of an invasion, or if they would view Germany as “the enemy of their enemy,” and remain passive.

A German invasion of Spain would have immediately triggered Operation Pilgrim, a British plan to capture the Hispanic islands of the Pacific. In this naval struggle, Italy may have been enticed to join the German effort to capture the islands, since after Gibraltar, these were considered the keys to the Mediterranean.

Finally, concerning the diplomatic intricacies of the situation, Franco was, prior to his meeting with Canaris, open to an alliance. "Spain wanted full economic support along with a list of territorial prizes in French North-west Africa, [..] French Morocco and the Oran district of Algeria. [..] Three days after Franco's offer to enter the war, Berlin had yet to reply, and the German embassy in Madrid had to ask its own Foreign Ministry what Germany's policy was."12

A forward looking policy would have realized that a German victory in France also necessitated a long struggle in North Africa, to eventually gain access to the Persia corridor and potential sources of oil. Such a policy would have immediately welcomed Franco into an alliance, not ignored him. The demands which Franco made over territory and future economic assistance could be simply promised regardless of the German ability to deliver. The immediate and swift capture of the Canaries, Azores, and Gibraltar would have a devastating affect on Britain’s Atlantic fleet. Once German troops were already established in Spain, Franco’s demand for a fulfillment of promises would be powerless. Franco could later be overthrown and replaced with another puppet, as occurred in Yugoslavia, negating whatever economic or territorial demands he made.

Quick and rapid action in the Iberian peninsula, whether by deceptive diplomacy, or by bloody battles, would have begun the North African campaign on an aggressive posture. German material losses during this campaign, which in the worst case may have risen to 100k causalities (as in France or Greece), may have been more conservative, similar to the Invasion of Yugoslavia or the Battle of Crete, at less than 10k casualties. The goal here would not be to minimize German casualties, as German manpower was not the limiting factor of the war. Rather, the goal would be to reduce British shipping, in order to impede both the flow of Lend-Lease to Russia, as well as to disrupt the supply of North Africa.

An Spain and Portugal would have succeeded in the Iberian peninsula. The ability of the Germans to successfully capture Cape Verde, the Azores, and the Canaries is less certain. At the very least, an Iberian-Atlantic campaign would have diverted British resources away from North Africa, and would have shortened the supply route from Europe railroads to North Africa by way of the Gibraltar strait. Although the British were supplying Suez by going around Africa, the capture of Gibraltar would impede any British attempt to go through the straits.

By easing the ability for Germans to access North Africa through Gibraltar, troops could be transported more quickly, cheaper, and safely across theaters. This would allow the Germans to invest more troops in the North African campaign, and to supply them more easily, while having greater flexibility to withdraw them if the Soviet Union launched a premature invasion.

Operation Tracer, a British observation post in Gibraltar, would have continued to monitor Axis movements. Operation Goldeneye would also be implemented to sabotage German efforts to control Spain.

If Germany was able to capture the Iberian-Atlantic islands, it would have been in a better position to impose not only greater pressure on the Persian corridor, but also on the arctic route, by intercepting vessels throughout the Atlantic. The material aid that America and Britain provided to the Soviet Union was absolutely vital to maintain the supply of Soviet troops, to prevent famine, and to maintain the logistical capacity of the Soviets to move troops via railway and truck. Without this assistance, Soviet encirclements of German troops, such as those at Stalingrad and Kursk, would have been less likely. Soviet reinforcements would have been more slow and sluggish, and less able to launch swift and dramatic counter attacks on the German salient.

North Africa and the Middle East

A survey of oil production in 1933 found that global production was equal to 1305M barrels. Most of these were produced in the USA: 781M barrels. Persia produced 49M barrels, and Romania produced less than 8M barrels.13 “Maikop and Grozny were each producing approximately 18.3 million barrels of oil annually. Baku [..] was capable of churning out a staggering 176 million barrels per year.”14

After the beginning of Barbarossa, the German war effort was entirely dependent on Romanian oil. Short of capturing the Baku oil fields, the next closest source of oil was Persia.

During the North African campaign, most Germans and Italians were not killed, but captured. Whereas only around 40k were killed, up to 500k were captured. This was due to the fact that German forces dedicated were too small to achieve victory. Had Germany doubled its forces, especially by gaining access to passage at Gibraltar, it may have experienced a higher rate of death, but would have compensated for this by preventing the surrender and capture of its forces. From a military point of view, 400k soldiers killed or wounded was better than 500k soldiers captured. This is especially true in light of the fact that the Balkan campaigns and the later invasion of Italy was only made possible by a continued British presence in the Mediterranean. By committing all available resources to North Africa in 1940, Germany could have prevented hundreds of thousands of lost soldiers later on.

The Syria–Lebanon campaign, which began in June 1941, was in response to the Anglo-Iraqi War a month earlier. Both of these campaigns had less than 40k troops on either side. Adding a few German divisions to this fight, in order to secure access to Persian oil and deny the Soviets a source of Lend-Lease aid, would have later on saved millions of German lives on the eastern front.

A Brief Note on Uranium

The Manhattan Project, which did not begin until 1942, was entirely dependent on Congolese Uranium, shipped out of Africa in September 1940 by Edgar Sengier.

Even assuming that the Germans achieved rapid success in Spain, taking Gibraltar in July, it would have been logistically impossible to launch an invasion of the Congo to seize the uranium before September. African roads, especially through the Sahara, did not allow for such quick movement. On the other hand, a series of submarine patrols, aided by some inside information, could have theoretically captured or sunk the shipment. The Germans did not have access to that kind of intelligence.

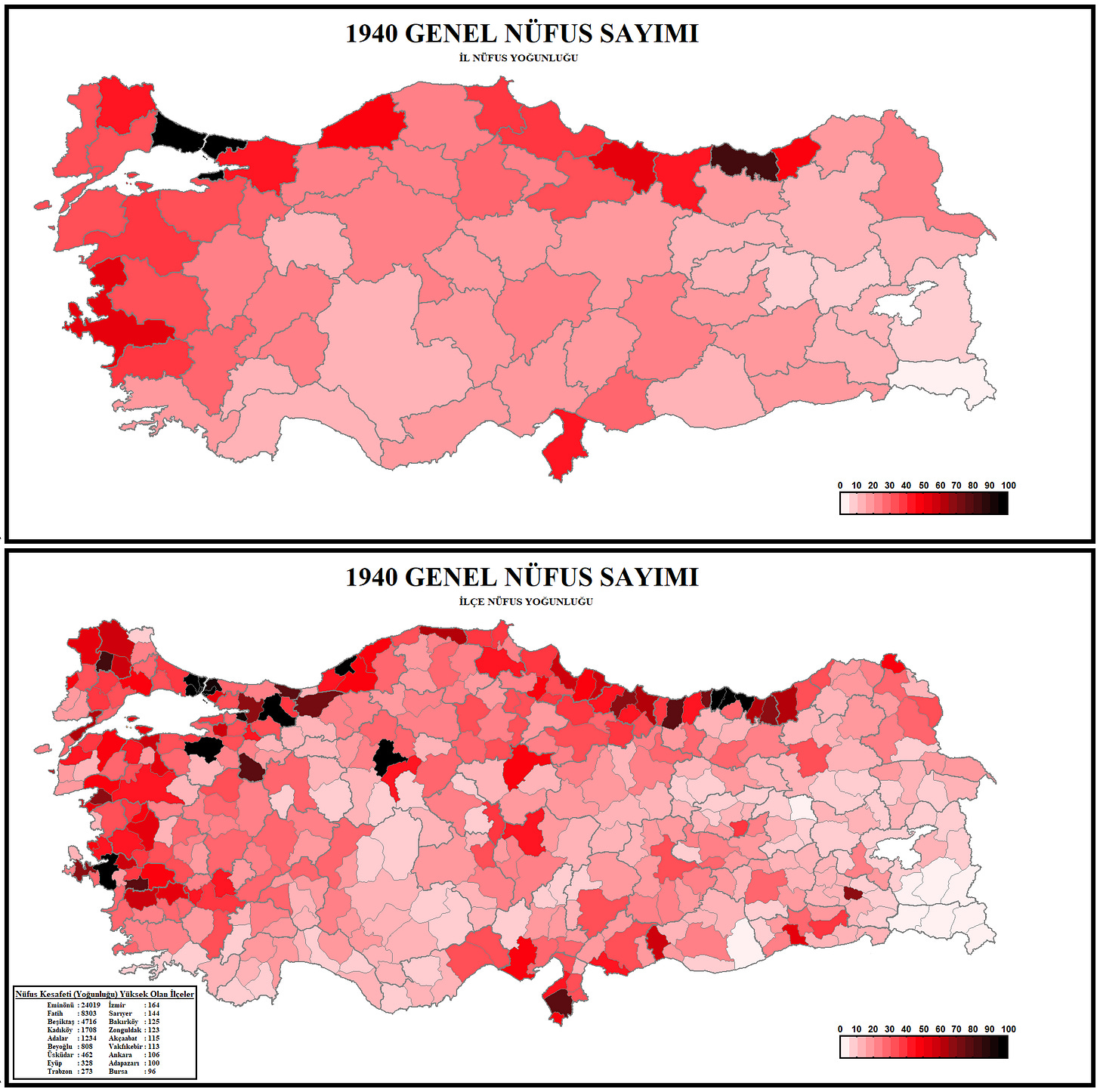

Operation Gertrud

To achieve maximum pressure on Britain, as well as Russia, the invasion of Turkey would be optimal. The Turkish population in 1940, at 20 million, was smaller than Spain. It was however larger than Greece, at only 7 million, which took 7 weeks and 20k German casualties. Part of the reason why the Greek campaign was such a disaster is that Italy had begun the campaign, in typical style, without consulting its allies, and had dragged things out for 6 months, allowing for the intervention of the British. A German strike on Turkey could have been better planned and less costly.

The biggest problem with an invasion of Turkey is that the cobalt and chromium mines, on which Germany dependent,15 could have been destroyed by the defending Turks, to deny Germany access, as had occurred in Greece.

The question becomes whether the dedication of 500k German troops to the invasion of Turkey would not be better served fighting for Suez. Logistically, it would be easier for the Germans to cross the Dardanelles strait rather than the Gibraltar strait, since it was at its narrowest point less than a mile, and the Çanakkale Bridge was already built across it in 1915.

Turkey, while providing a quicker and easier root to Iraq and the Caucasus than Spain, did not confer all the benefits of a Spanish invasion, in that it did not strategically impact on the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Therefore, if only one of these campaigns was possible, it was preferable to choose Spain, since it would provide both an offensive base for operations in the Atlantic, as well as a defensive base of operations for the Mediterranean. Turkey, by contrast, would only allow Germany easier access to offensives into Iraq and Russia, without affecting Atlantic shipping or the naval balance in the Mediterranean. With Turkey conquered, Britain and America would still have the same advantage in both the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and would use this to protect Suez and supply Russia, and eventually to threaten Yugoslavia, Greece, and Italy.

Assuming that German campaigns in Spain and Turkey would both be possible simuntaneously, requiring armies of less than 1 million troops each, each receiving less than 100,000 casualties, then these casualties would have been tolerable in light of the millions more saved by a successful operation Barbarossa, enabled by the stifling of Lend-Lease.

While the fall of France in June 1940 enabled an immediate invasion of Spain, Bulgaria, which protected Turkey’s European border, did not join the Axis until March 1941. This makes a simultaneous invasion of Turkey almost impossible, unless Bulgaria is forced to join the axis at a much earlier date by military pressure. As a country of 6 million, this would not have been impossible to produce, but would destroy the element of surprise. A military solution to the slowness of Bulgaria to join the Axis might result in Turkey accepting the British offer of an alliance.

With Spanish society being deeply divided and only a year recovered from a terrible civil war, and the Falangists available as a possible fifth column, an invasion of Spain was more attractive than an invasion of Turkey. Turkey had been modernizing in peace for 20 years, and the terrain was rougher and more difficult to traverse than Spain.

It is not clear that a German invasion of Turkey in August of 1940 would have been feasible, especially considering the position of Bulgaria. While pressure could be exerted on Bulgaria to expedite its adhesion to the Axis, the invasion of Spain may have created doubts among potential allies, such as Bulgaria, of German’s diplomatic honesty. Neutral countries like Bulgaria and Turkey, fearing to suffer the same fate as Spain, might invite British cooperation.

The risk of alienating Bulgaria by a Spanish invasion would be risky, but might also intimidate the Bulgarians into an alliance even sooner.

Conclusion

At the end of the Second World War, millions of German soldiers were confined to prisoner of war camps. Many were used as slave labor. Many died while in captivity. This should help dispel the notion that Germany lacked, principally, manpower. WWII was not determined by superior manpower, but by superior resources. This is especially true for Russia, which suffered much higher casualties than in did in WWI, but as a result of Lend-Lease, was able to successfully conclude the war.

While military strategy is often thought in terms of the positioning of armies — Moscow or Stalingrad? — a material or resource-based geostrategy will conclude that Lend-Lease was the fundamental difference between Soviet victory and defeat. While Germany could not completely close the artic route, nor could it control Vladivostok, it did have the resources to invade Iraq and significantly disrupt the Persian corridor.

Germany dedicated more resources to the invasions of Yugoslavia and Greece than it did to North Africa. Yet a successful North African campaign would have made these campaigns less essential and possibly avoidable. By avoiding committing forces to North Africa, Germany later had to commit much larger forces to the defense of Italy. Such a defense would have been entirely unnecessary if those same forces were earlier committed to the capture of Gibraltar and the Suez.

In June of 1940, Germany had a host of advantages on its side. The German army in France was already on the move, and had momentum on its side. Spain was open to joining the alliance, and the terms which Spain demanded were acceptable on the conditions that “it is easier to ask forgiveness than to ask permission.” In other words, German promises to Spain, if they were found at a later time to be impossible to fulfill, could have been ignored once a German military presence was already established. While this would not have been an honorable policy toward Spain, such a policy would have been fair and reciprocal, given Franco’s collaboration with the British spy, Admiral Canaris.

Furthermore, Germany’s fear that Spanish demands would alienate France would later become completely irrelevant, since Vichy France had to be forcibly occupied during Case Anton, November 1942, due to its negation of peace with Germany. A German occupation of Spain, recommended by the most highly rated German generals, including Guderian and Jodl, would have been possible to achieve in by 14th July 1940, with a siege of Gibraltar likely lasting two weeks and being concluded on August 1st.

On the 14th March 1939, Göring and Ribbentrop forced Emil Hacha to sign away his country to German occupying forces. They presented him with an ultimatum, that if Hacha did not agree to surrender, the destruction would be immense. If that same technique was used on Franco, it is unknown whether he too would submit, or else attempt a futile defense of Spain. Depending on whether Franco would collaborate, the capture of Gibraltar could be achieved as quickly as the 7th of July.

Simultaneous with a land-based operation against Spain and Gibraltar would be a naval operation in the Canaries, Cape Verde islands, and the Azores. Franco did not have sufficient resources to defend against a British attack, but it is unknown as to whether Germany could have defeated his forces there, as in the case of the German invasion of Norway. Due to the destruction of the Spanish Civil War, it is possible that the Norwegian fleet was larger than the Spanish fleet.16

The distance from the German port of Bremerhaven to Narvik was roughly 2500 kilmeters. The distance from Bremerhaven to the Iberian-Atlantic islands ranged between 3500 and 5500 kilometers. This would have been a difficult mission for the German navy, but not impossible. Furthermore, this would have been one of Germany’s few possible practical use for its above-sea navy in an offensive capacity.

Again, while German campaigns to take the Iberian-Atlantic islands would have been a costly gamble, it would have been an investment in the future. The campaign in Malta ultimately cost the Axis 23% of its merchant fleet, and 72% of the Italian transport fleet. If such forces were committed to the Atlantic campaign in June of 1940, they could have been potentially saved later in a successful campaign against Malta. By denying the British access to Gibraltar, and adopting a more aggressive submarine campaign in the Atlantic, the British capacity in Malta would have been diminished.

All of this would require the element of surprise, as in Norway. If a simultaneous expedition was not launched, then the British navy would have beaten the Germans to the punch. If a secret agreement with Franco could have been concluded, then a successful occupation would be made more likely.

On the other side of the Mediterranean, threatening tactics could have been employed against the Tsar of Bulgaria, in order to gain access to Turkey. Assuming that such a campaign could not be undertaken prior to the capture of Gibraltar, it is possible that the issue could have been forced in August. At the earliest, it is difficult to imagine a German invasion of Turkey prior to September of 1940. Such an invasion would be similar in scope to the invasion of Greece or Yugoslavia.

Geographically, Turkey was larger than France (551K km2) and Spain (500K km2) and (784K km2).

Turkish GDP per capita, however, hovered around $1500, roughly 20% of the level of France, and 40% the level of Greece.

Given the almost primitive nature of the Turkish economy, it is possible to compare likely Turkish performance in WWII with Iraqi or Iranian performance. That is to say, against a modern European army, the Turkish army would have collapsed twice as easily as Greece. A three week campaign in Turkey would be sufficient to secure a German corridor in that country and install a puppet government. This would open up a new front in the middle east from which to reinforce Vichy Syria, invade Palestine and Iraq, with the twin goals of shutting down Suez and also launching a campaign into Persia.

It could be objected that Germany did not have the manpower to launch expeditions into Spain, the Atlantic islands, Egypt, Bulgaria, Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, or Iran. If we assign each of these expeditions a potential casualty risk of up to 100k troop each, this comes out to a total of nearly 1 million German casualties. Could Germany have suffered 1 million casualties, and still launched Operation Barbarossa? And without Barbarossa, could Germany withstand a Soviet surprise attack on Prussia and the Romanian oil fields?

As demonstrated by the 3 millions Germans in prisoner of war camps in 1945, Germany did not lack manpower by the end of the war. Rather, it lacked resources, and it lacked the ability to deny resources to its opponents. Instead of allowing these soldiers to be captured by surrenders and encirclements, if they had instead been sacrificed in campaigns to disrupt the Atlantic passage; to disrupt the Persian corridor; to open up an earlier Caucasian front against the Baku oil fields at the beginning of Barbarossa; to capture Gibraltar and the Suez; then two million prisoners of war might have been saved. By conserving its forces between 1940 and 1942, Germany may have sought to prolong the war, but this resulted in eventually surrenders and encirclements.

The German prosecution of the war in 1939 can only be justified if a Soviet attack in 1942 was imminent. If that were the case, then Germany had three years to prepare and reorganize Europe in order to launch a preemptive strike. Assuming that a Soviet invasion of Romania was inevitable, then the German supply of oil would have been immediately lost. Barbarossa, given these assumptions, was necessary.

Yet Barbarossa was also logistically fraught. The marshes of Russia, combined with the oddly-gauged railroads and poor roads, made supplying the invading German troops almost impossible. By the time that the Germans approached Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad, their supply lines were stretched to the breaking point. Even if they had taken these three cities, they could not have advanced much further.

The failure of Barbarossa, therefore, was not due to an insufficiency of troops. The Germans were not able to transport any more troops. The argument that German casualties in a North African or Middle Eastern campaign would have harmed Barbarossa is not accurate. The supply lines of Barbarossa could not handle additional strain.

The most crucially limiting factor on German logistics was oil. The Romanian oil fields supplied the entire German war machine, and they produced less than 20% of the oil in Persia, and less than 4% of the oil in Russia. Sacrificing German lives for a better chance at access to this oil may have ultimately saved German lives, since it would have allowed the Germans to overcome later logistical limitations.

Even with a successful campaign against Turkey in September of 1940, the British would have destroyed the Persian oil fields before the Germans could access them in October, by filling them with concrete. At the very least, it would have taken the Germans two years before they could fix the sabotage done, and build oil pipelines that could transport this oil back to Germany. Germany would not likely have seen an increase in oil production until November of 1942 at the earliest — but this would have made a significant difference in the outcome of the war.

Even if Germany failed to utilize Persian oil, the denial of the Persian corridor for Lend-Lease would have disrupted the mobility of more than 10% of the Soviet forces. In other words, out of the 34.4 million Soviet soldiers drafted, 3.4 million would have been without the logistical capacity to operate effectively in the field. This would have prevented the encirclement of German forces, preventing their capture and allowing for their redeployment in defensive actions.

It is possible that even if Germany had imposed 5 million additional casualties on the Soviet Union, it still could have fielded a small force of 1 million soldiers. Since America had registered 50 million men for the draft, and 26 million of these could have been plausibly deployed in Europe, it is possible that a Soviet Union on the brink of collapse could have still held out against a German attack from the Urals, even one which disabled the Baku oil fields. In such circumstances, the war in Europe could have dragged on for several years more, with the Germans unable to knock the Soviets out of the war, and the Americans vastly outnumbering the Germans.

That said, with the strategic situation set in stone in 1940, the best chance of a German success against the Soviet Union lay in its ability to disrupt Lend-Lease, and that meant and aggressive offensive in the Atlantic, Spain, Gibraltar, North Africa, Suez, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. If possible, a pressure campaign against Bulgaria (in the worst case, an invasion) and an invasion of Turkey could have sped up the German invasion of Iran, and shortened the German supply lines. The political will of the Spanish and Turks to resist German occupation would have been a decisive factor in the success of these operations.

Technologies such as nuclear weapons favored the America victory in war, but hypersonic missiles and jet aircraft favored the Germans. The effect of these inventions, given additional time and resources, is unknowable. At the least, a German expenditure of manpower into the Atlantic and the middle east would have denied the Soviets crucial resources which they needed to fight effectively in the field. Although a total blockade of the Soviet Union was impossible due to Archangelsk and Vladivostok, significant progress could have been made with a more active, aggressive, and geostrategic posture. The German hesitance to commit troops to North Africa for the sake of conserving manpower was not proven to be prudent by the end of the war, when 3 million fighting age Germans were interned in prisoner of war camps, or worse, gulags and slave labor camps. Expending that manpower prior to Barbarossa in order to deny the Allies access to resources would have paid dividends later in the war.

In WWI, the Russian collapse came as a result of a lack of equipment, with 76% of its fighting age men knocked out of the fight. Russia still had troops, but no rifles to give them. In WWII, the Soviet Union lost 84% of its fighting age men, but still conquered Berlin as a result of additional supplies from Lend-Lease. Denying the Soviet Union access to those supplies could have exhausted its military and led to a truce very similar to Brest-Litovsk. With enough oil and food, Germany would have then been able to focus on defending its coastal borders for an inevitable American invasion. Whether such an invasion could succeed or not would be highly dependent on the American political will to prosecute the war, no matter the duration or cost.

Afghanistan was successfully made into a communist country in the 1980s. The Soviets had much more military success in Afghanistan than the Americans in Vietnam. The Soviet Union collapsed for reasons of political espionage and internal corruption in 1989. The Soviet puppet government survived three years after the fall of the Soviet Union, until the communist Afghan government fell under pressure from the CIA and Pakistan.

Krivosheev (1997). Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century. pp. 51–97, 79. ; Krivosheev, (2001). Rossiia i SSSR v voinakh XX veka: Poteri vooruzhennykh sil; statisticheskoe issledovanie.

Lev Lopukhovsky, Boris Kavalerchik (2017). The Price of Victory: The Red Army's Casualties in the Great Patriotic War.

Zaloga, Steve. Armored Thunderbolt: The U.S. Army Sherman in World War II. (2008) pp. 28, 30-31.

Weeks, Albert (2004). Russia's Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II. p. 9, p. 146.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170506174749/http://www.history.army.mil/books/AMH-V2/PDF/Chapter05.pdf

Ward, Steven (2009). Immortal : A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces. p. 176.

This was not primarily due to the genius of Alan Turing or of Polish code breakers, but because of the assistance from the head of German intelligence, Admiral Canaris.

Eccles, David, By Safe Hand: Letters of Sybil & David Eccles: 1939–1942 (London: Bodley Head, 1983), p. 15. From: Building an Empire and Bringing About a Famine: The Allied Economic Blockade of Spain during the Second World War (1939–1945). Contemporary European History. Published online 2023. doi:10.1017/S0960777322000959

Also see Christian Leitz (1996). Economic Relations between Nazi Germany and Franco’s Spain 1936–1945. “Nazi Germany’s Struggle for Spanish Wolfram and Allied Economic Warfare”: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206453.003.0006

Bowen, Wayne H.; José E. Álvarez (2007). A Military History of Modern Spain. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 114. Archived.

The Riddle of the Rock: A Reassessment of German Motives for the Capture of Gibraltar in the Second World War. Norman J. W. Goda Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 297-314: https://www.jstor.org/stable/260712

World Oil Production: https://doi.org/10.1038/132344d0

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1020261.pdf

William Hale (2021): Turkey and Britain in World War II: Origins and Results of the Tripartite Alliance, 1935-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2021.1987764

The Norwegian fleet included 7 small destroyers, 26 torpedo boats, 9 submarines. The Spanish fleet in 1936 included two dreadnoughts, one heavy cruiser, one large destroyer, and 6 submarines. These were destroyed during the Civil War.