National power projection is not possible below the “axis of negation.” The axis of negation is the average IQ at which the social problems caused by low human resources “negate” the creative or inventive power of genius, in terms of national power projection. This is not to say that Subsahara, for example, will not produce thousands of geniuses throughout the next century. Some of those geniuses will leave Subsahara, become scientists, chess players, writers, or political leaders.1 However, within their home societies, these geniuses will not be able to marshal the human resources of their countries to project power outward.

Rapid population growth within Subsaharan countries will create a massive political and security problem for Subsaharan military and logistical forces. Each country will be bursting with crime, corruption, and the constant threat of mass starvation. Ukraine supplies 90% of the wheat in East Africa,2 and the war in Ukraine brought extreme hunger to more than 23 million people. With Somalian pirates and Houthis threatening global supply lines, and isolationists like Tucker Carlson lobbying to bring home the “global police,” the Subsaharan food supply stands at the precipice of disaster. Whether the catalyst is a war with China, another pandemic, a global cyber attack, a solar storm, or an insurrection, any slow down of the global economy will result in millions of starving Africans. Such a fundamental crisis (the inability of a government to feed its populace) will exacerbate instability and require massive military reserves to resist total collapse and civil war. Any Subsaharan government which seeks to project power outward will find itself spread too thin.

Subsahara’s problems would be more manageable if the population was smaller, so that native Subsaharan food production could satisfy native demand. However, a smaller Subsahara in terms of population would be even less likely to project power. Although the problem of food insecurity might make it seem like human resources are less important than natural resources, other net food importers such as Germany have used their human resources to overcome agricultural limitations.

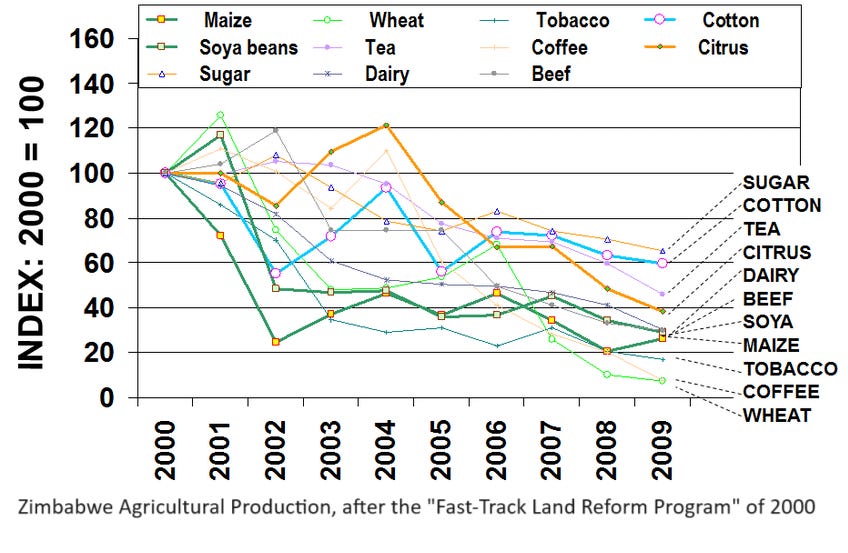

One stark example of how low human resources causes famine is the “Fast-Track Land Reform Program” in Zimbabwe, first enacted in the year 2000.3 The program was an armed insurrection against legal landowners, who were overwhelmed by sheer numbers, kidnapped, tortured, killed, and dispossessed of their land.4 The farms were taken over by militant gangs with lower human resources than the farmers they expelled. As a result, over the next 9 years, agricultural production fell from a minimum of 35% (sugar) to a maximum of 90% (wheat).

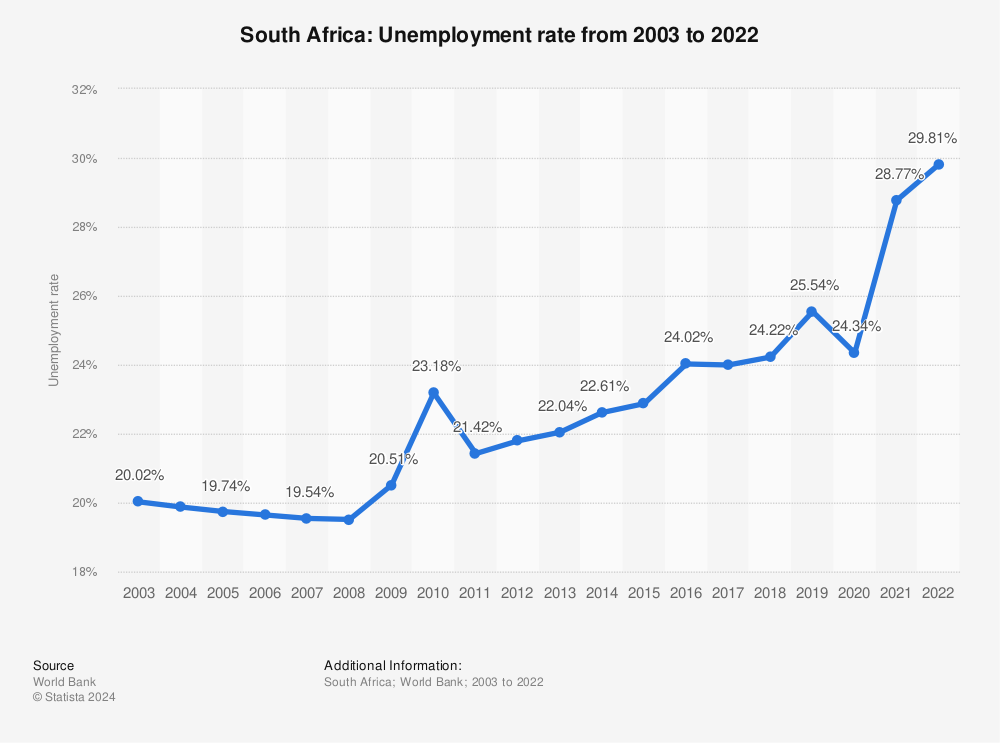

A similar story can be told in South Africa. South Africa is especially important because (as Subsahara’s most developed and largest economy) it is the best candidate for “power projection” abroad. However, despite backing from the international community, the new constitution, implemented in 1997, has resulted in sky rocketing unemployment and the breakdown of basic services.

Reserve Margins and Loadshedding

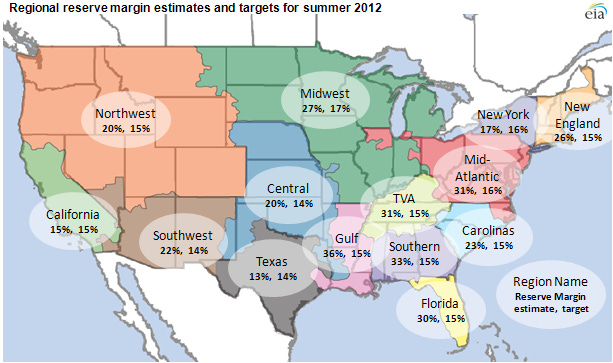

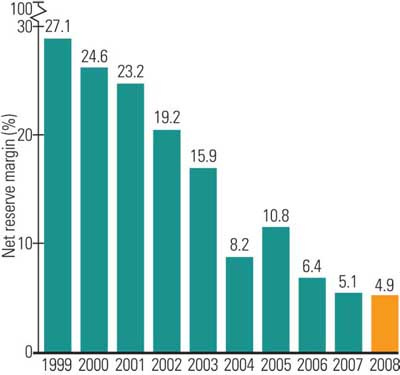

Since 1999, South Africa has seen a dramatic reduction in its reserve margin. The reserve margin is the amount of unused capability of an electric power system during peak usage as a percentage of total capability.5

In America, reserve margins generally fluctuate between 36% and 14%.6 In China, reserve margins have been built higher to accommodate expected economic growth, averaging 28%, but in some regions as high as 64%.7

From 1999 to 2007, South Africa saw a reduction in its reserve margin from 27% to 5%. As a result, South Africa began experiencing rolling blackouts in 2007, known as "loadshedding." In order to resolve this problem, the first post-apartheid power station was commissioned. This new station, the Medupi Power Station, was initially expected to cost 80 billion Rands in 2007. When the project went over budget, the World Bank provided $7.8 billion dollars in aid for its completion. It ultimately ended up costing 234 billion Rands by 2019. The budgetary mismanagement was so bad that in 2022, the African Development Bank declared that the plant would never generate more revenue than its final cost, and that the project represented a failure for South Africa.8 The taxpayers would have been better off had it never been built.

Why did the project go so far over budget? Besides general strikes and incompetence, the worksite of the power plant erupted into violent mayhem over several years, in which enraged workers directly sabotaged and destroyed equipment. In 2011, riots and destruction were already underway. “The damage consisted of the burning of an office, a bus, and two cars; and in addition three cars were overturned.”9 In 2013, 1,000 workers flipped cars and attacked police.10 “Generators, cars and cranes were destroyed and burnt in violent strikes.”11 Again, in 2014, hostility, suspicion, and death threats lead to a full five month interruption. Finally, in 2015, buildings were burnt to the ground by 1,400 workers. Flaming buses were flipped over and used to barricade roads. Project coordinators alleged that the rioters were high on a heroin derivative called "nyaope."12 Only two weeks after the project was finally completed, the generator experienced an explosion which ended up costing 40 billion Rand — almost half the initial estimated cost of construction.13

The second post-apartheid station, Kusile Power Station, began construction in 2008, and was scheduled for completion in 2014. However, all units of the station were not completed as commercially viable until 2022. Like the Medupi station, rioting workers caused millions of dollars of damage, setting vehicles, offices, and cranes on fire, complete with general smashing and looting.14

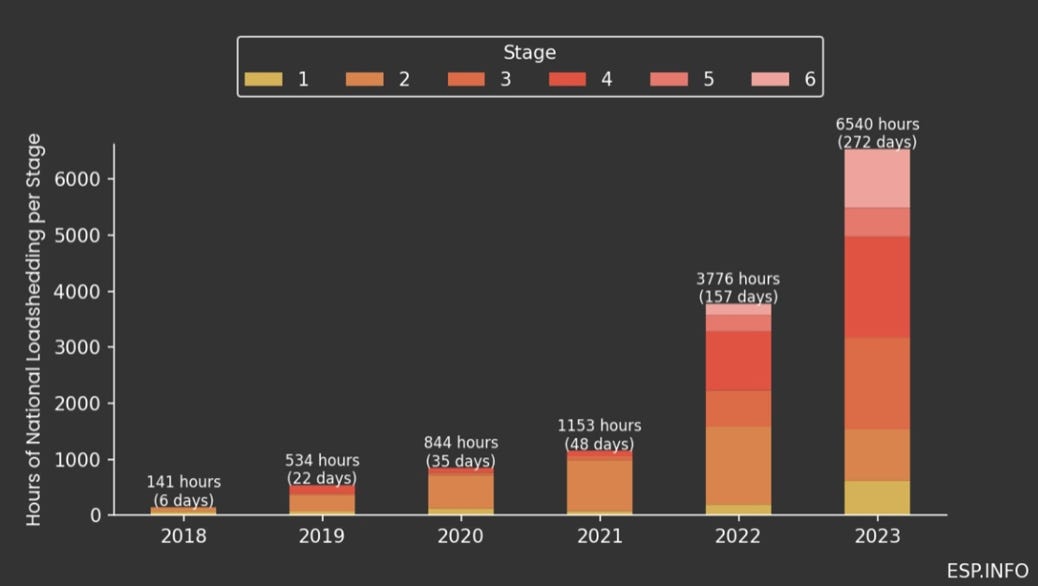

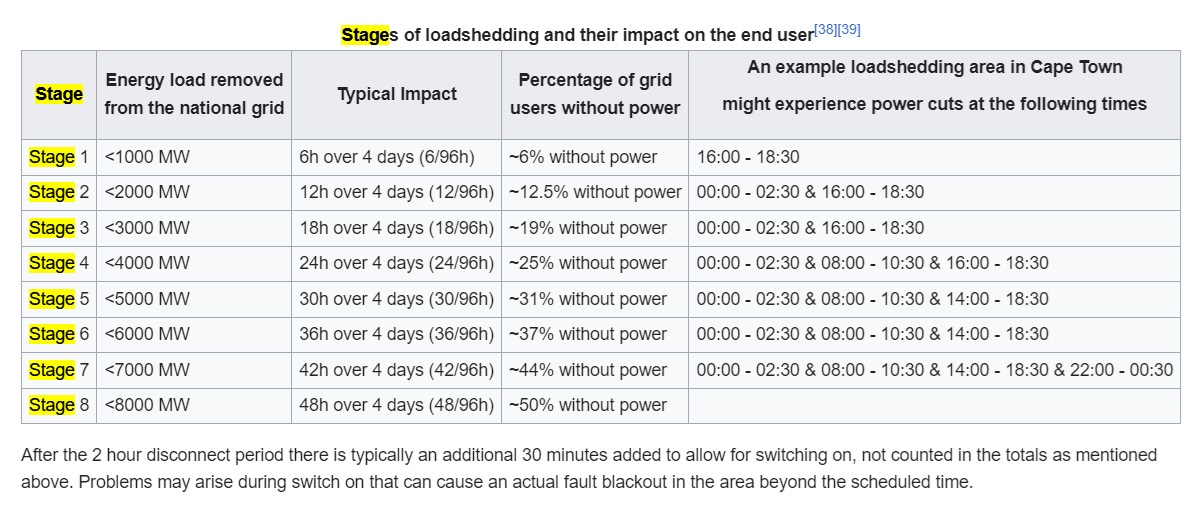

Although both Medupi and Kusile both became fully operational in 2021 and 2022, South Africa’s blackouts have gotten worse and worse. Since 2019, South Africa has set all-time records for increasing hours of blackout, with each year since then beating the old record. In 2023, South Africa was experiencing blackout conditions 3 out of every 4 days. Stage 6 blackouts, which were introduced in 2019, represent blackouts where 37% of the country is without power. In 2023, thieves destroyed electrical infrastructure in order to steal parts and scrap metal, with incidents of theft being noted several times a week, without any successful counter measures from law enforcement.15

In essence, Subsahara’s various governments, ranging from Nigeria to South Africa, all are threatened by substantial economic instability and military conflict. These states cannot solve the basic logistical problems of keeping the power on in their own countries, let alone invade their neighbors or project power outwards. If South Africa, which possesses the most powerful military in Subsahara, cannot protect its own powerlines from being ripped apart by thieves and scrap metal sellers, it is difficult to imagine it promoting its interests abroad.

The axis of negation prevents countries with low human resources from projecting power, even as they increase in population. It does not matter if the Congo has a population of 100 million or 1 billion — as it grows in population, the logistical problem of maintaining basic infrastructure will balloon, leading to internal pressures, conflicts, and power struggles. This is a road to nowhere.

The Road to Nowhere

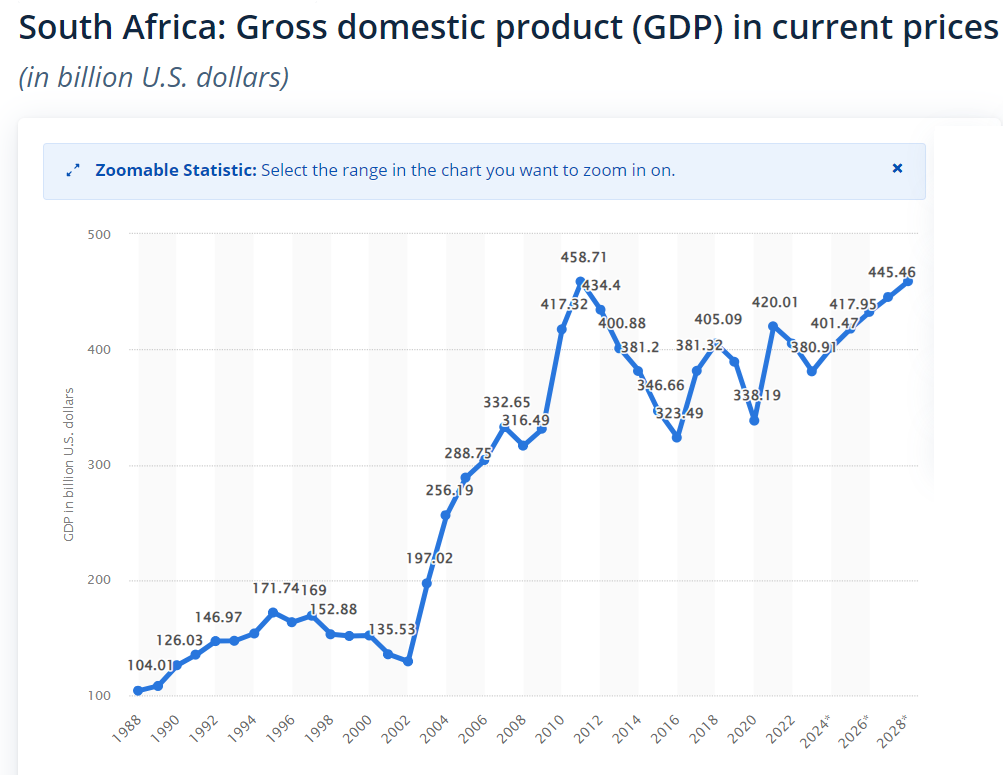

In 1986, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act was passed. President Reagan described apartheid as "a malevolent and archaic system totally alien to our ideals."16 The sanctions had a crushing effect on the South African economy, and led directly to the ascension of Nelson Mandela and the ANC. Sanctions were fully lifted in 1995, which, theoretically, should have led to unprecedented growth.

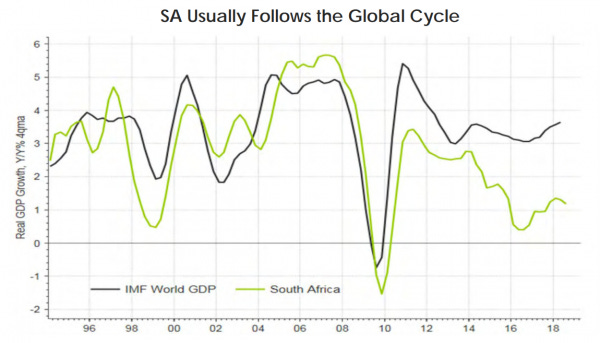

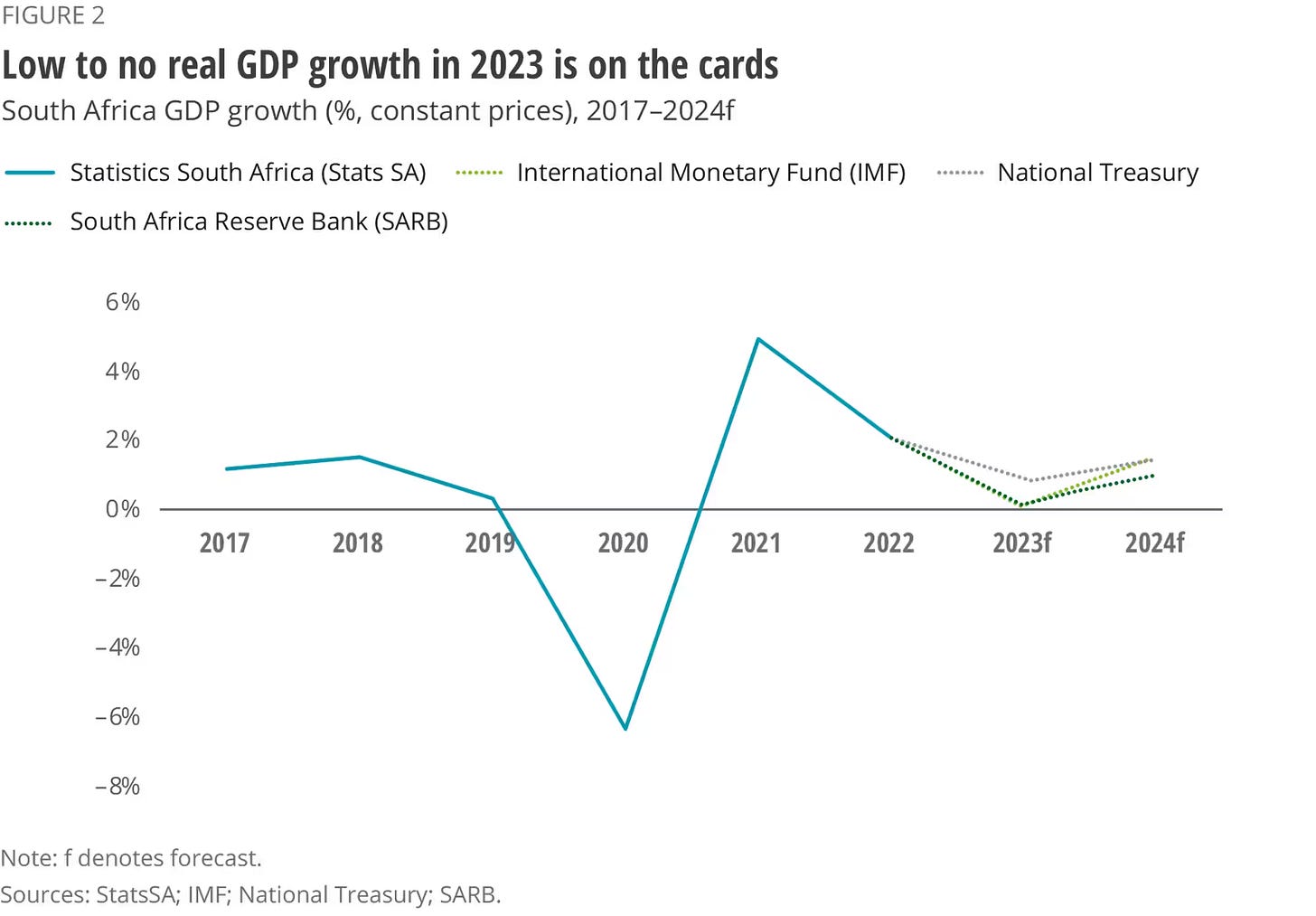

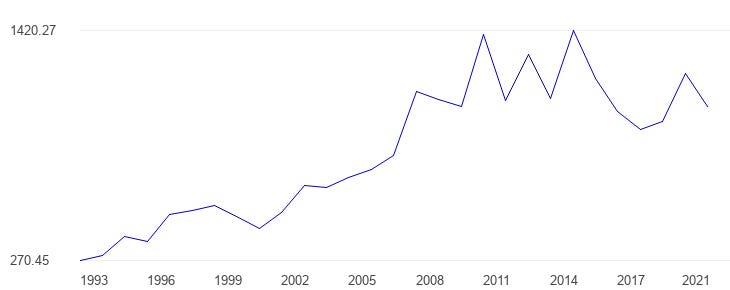

At the same time that the sanctions were lifted, South Africa received a massive influx of global investment between 1993 and 2011.17 Foreign aid increased from $270 million per year to over $1.4 billion per year around 2011. Since 2011, increases have stalled and, as a result, the South African economy has lagged behind the global average. While global GDP growth has remained above 2% on average since 1994 (with the exception of 2009-10 and 2020), South African GDP growth has stalled and fallen well below the global average since 2010.

The lifting of sanctions and massive influx of cash between 1993 and 2007 entirely explains and accounts for South Africa’s post-apartheid growth. However, after foreign aid stopped exponentially increasing in 2011, and with the post-sanctions boost evaporated, South Africa has begun a 13 year long descent into de-industrialization. Since 2018, the pace of de-electrification has intensified, reaching record new levels with every year, leaving between 6% to 37% of South Africans without power for 6 to 36 hours every four days. Nuclear power has been offered as a solution, but the earliest plants are not scheduled to come online before 2033. The crisis which has only grown since 2018 can be symbolized by cultural changes. Since 2017, South Africa has not featured any women of European descent in their Miss South Africa beauty pageants, reversing the trend set first in 1956.

Rich Whites Insulated from all Disaster

Why did South Africa begin the policies which have led to disaster? It may have something to do with the fact that South Africa’s richest families have escaped unscathed and have been unaffected by the socio-economic collapse. Of the 7 richest South Africans, two are Jewish (Ivan Glasenberg and Nicky Oppenheimer), one is black Tswana (Patrice Motsepe), and one is Chinese (Patrick Soon-Shiong). The other three (Johann Rupert, Koos Bekker, and Michiel Le Roux) are white. Other contenders for the top 10, including Desmond Sacco and Christoffel Wiese, are also white.

Not all wealthy South Africans have remained in the country. Roelof Botha, for example, is the grandson of Pik Botha, one of the first white ministers in the Mandela government. While Elon Musk was the CEO of Paypal (then known as x.com), Roelof became director of corporate development. Later, during Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, Roelof would direct Sequoia Capital to aid Musk, providing $800 million toward the purchase.

Tony Trahar, another South African success, began working for Anglo American in 1974. Anglo American is the largest company in South Africa. Today it is the 8th largest in the world, but at the time it was the 2nd largest mining company. Following apartheid, Trahar became the CEO in 2000.

The second largest company in South Africa after Anglo American is Sasol, an energy and chemical company, which is run by Fleetwood Grobler.18 The third largest company, Shoprite, is run by Wendy Lucas-Bull and Pieter Engelbrecht.

Stephen Saad, a South African billionaire of Lebanese descent, has seen his wealth more than double in the last 14 years. Together with Gus Attridge, he founded Aspen Pharmacare. Aspen was granted a license by the South African government to develop HIV antiretrovirals in 2001. In 2021, Aspen signed a contract with the South African government to produce 31 million doses of COVID vaccine, enough to vaccinate the majority of South Africa’s population (38 million shots were administered in total).

Out of the nine members of the board of directors of Aspen, five are of European descent (not counting Lebanese), while one, Yvonne Muthien, belongs to the Colored minority. Only two members are part of the country’s black majority. Of the 10 members of the group executive committee, 6 are white (not counting Lebanese), 2 are colored, and 1 is black.

Looking back to the events of 1994, why did white minority politicians not resist the fall of apartheid? One case study would be that of Roy Cecil Anderson. Anderson was promoted to Major General in 2003. Previously, he served as the Executive President of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange from 1992 to 1997. Currently, Anderson sits on the boards of Murray and Roberts Holdings, Sanlam Limited, Virgin Active Group, and Aspen Pharmacare. Although he stepped down in 2021 from his military position, it may seem odd to an American audience that an active member of military command was also sitting on the board of directors of so many different companies. Due to the highly political nature of the South African economy, and its high level of corruption, a skeptical mind might ask if Anderson was not being bribed with do-nothing corporate positions to maintain the military’s loyalty to a crumbling and decaying regime.

Indian Influence

Another factor in the fall of apartheid was the country’s Indian minority. Schabir Shaik, an Indian-descended South African, was part of the ANC, and saw himself in an alliance with blacks against white supremacy. His brother, Chippy Shaik, held a key position in the Department of Defense, which allowed the brothers to profit off of the government through nepotism. After his arrest for corruption, Schabir was given permission by the court system to enjoy his parole in a luxury lodge.

South Africans of Indian descent are even more infamously represented by the Gupta family. The family became infamous in 2017 for deliberately manufacturing racist tensions to further its own aims. The Guptas hired British public relations firm Bell Pottinger to create fake Twitter botnets promoting racism against whites in order to distract from its own corruption scandal. The ploy was to inflame black resentment against white people, and to portray Indians as allies of blacks in the fight against “white monopoly capital.” Exposure of this scandal led to the immediate bankruptcy of Bell Pottinger, and the Gupta family fled the country.

The Guptas cannot be said to represent all Indian-South Africans, as they were opposed by Indian-South African politician Pravin Gordhan. Gordhan is the current Minister of Public Enterprises, who oversees the following state controlled companies: Alexkor (diamond mining), Denel (weapons manufacturing), Eskom (energy), South African Express (transportation), South African Forestry Company (lumber), and Transnet (railways, harbors, and oil pipelines). Although Gordhan is not part of he Guptas, and opposed them, he still represents significant Indian over-representation in South Africa.

Black Economic Empowerment

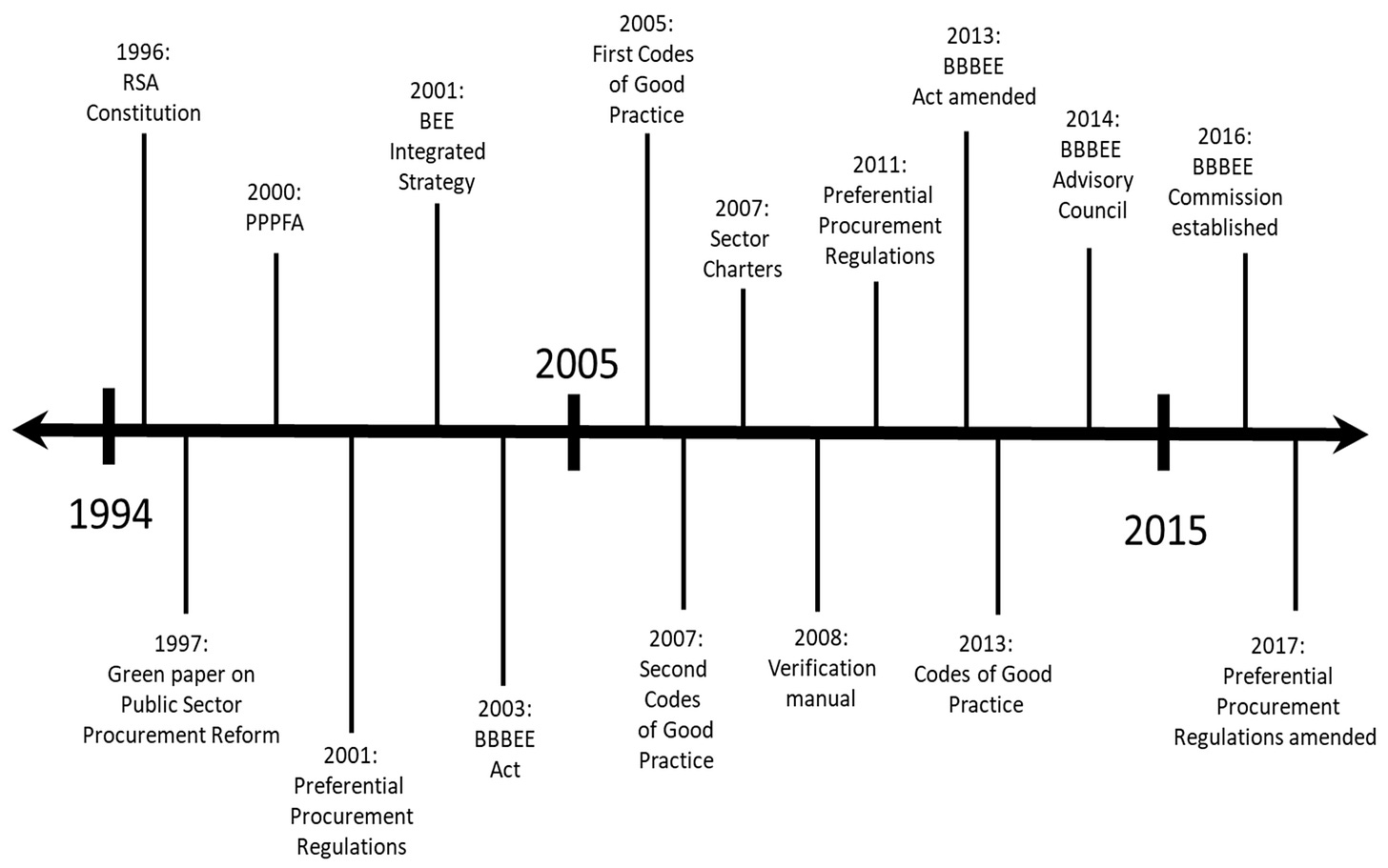

Since 2003, the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE or simply BEE, hereafter referred to simply as “Empowerment”) program has favored companies which appoint blacks to their board of directors and other voting positions. According to the text of the law, ““black people” is a generic term which means Africans, Coloureds and Indians.” In a 2008 supreme court ruling, even Chinese people were considered “black” for the purposes of the law.

If Empowerment has been part of South Africa’s overall slide into disfunction, has it at least promoted equality? One study found that “BBBEE has failed to successfully empower the majority in the labour market or the underclass of a large unemployed sector. Racial inequality therefore only declined at the very top of the income bracket.”

BBBEE results in the enrichment of a small percentage of blacks: “Enrichment refers to the unintended consequence of the design of BBBEE that resulted in a few socially and politically connected black people benefiting from empowerment deals.”19

Additionally, “it has become a compliance exercise. Entities that implement BBBEE do not believe in the benefits of the intervention’s initiatives but instead implement it as a compliance requirement. As a result, these entities often regard transformation as separate from their core business and do not integrate it into their strategies and annual business plans.” In other words, blacks are placed in executive positions on paper without those positions having relevance to the actual decision making process.

This process is known as “fronting”: “The BBBEE Act defines fronting as “a transaction, arrangement or other act or conduct that directly or indirectly undermines or frustrates the achievement of the objectives of the BBBEE Act or the implementation of any of the provisions of the Act.” Fronting practices [..] include window dressing which involves the introduction or appointment of black people to a business purely based on their race. People who are appointed are often discouraged and prevented from participating in the decision making and core activities of the business.”20

Conclusion

Between 2002 and 2011, South Africa achieved massive economic growth due to the removal of sanctions and an influx of both foreign aid as well as foreign investment. The proximate cause of South Africa's decline in GDP was Jacob Zuma's presidency from 2009 to 2018, but the deeper causes were already present in 2007 when rolling blackouts began. 900,000 South Africans have left the country since 1994, and the rate of emigration is speeding up, leading to brain drain.

A full understanding of the process which lead to the end of apartheid will focus on the 1994 election, including allegations of voter fraud and the actions of Constand Viljoen.

In an article which has since been wiped from the internet, but preserved by the Wayback Machine,21 anti-apartheid activist Professor Steven Friedman, director of the Centre for the Study of Democracy, said the following:22

When an election result in a society at war with itself is exactly what some academics say it must be to stop the conflict, it is fair to ask whether votes were counted or agreed by negotiation.

Which explains why our first democratic election turned out how some experts said it should.

We often romanticise democracy’s beginnings: the first vote, in 1994, is remembered with great fondness.

But, while the people’s conduct on those days was inspiring, the way the ballot was run and votes were counted was not: the election had to be saved by a bargain between the major parties.

Its lesson is not how efficient we can be as a nation but what can be achieved if we bargain and compromise.

Throughout the negotiations which produced the election, the ANC insisted that it wanted decisions taken by representatives of the majority, while the National Party and its allies wanted them negotiated between the parties.

The election settled the battle in favour of – both. Everyone took part and the most popular party won: this gave it credibility among citizens.

But the fact that it was negotiated between the parties prevented rebellion and allowed democracy to begin.

My knowledge of the election was first-hand: I was head of the Independent Election Commission’s (IEC) information analysis department. It was our job to make sense of reports from election monitors so the IEC would be aware of threats to the election.

But we were also asked to advise it on a test of a free and fair election.

We came to the conclusion that beyond the obvious – every adult needed the right to vote, and all votes must be counted accurately – there was no formula for whether an election was free or fair.

Even if an election was run perfectly, it would achieve nothing if the losers did not accept the result (winners, of course, always accept the outcome).

And so the test was whether the IEC could win the confidence of all parties; negotiation with and between political parties was far more important than running the ‘perfect’ election.

Although this was not a popular view within the IEC, it described exactly what happened.

The election was a technical shambles – which was hardly a surprise. No one here had ever run an election for everyone: the IEC was staffed by lawyers, academics, political activists – and one or two election managers.

We had no voters rolls and, in places neglected by apartheid, no infrastructure.

And so huge queues formed on election day and it took some people days to vote.

The IEC was staffed not by neutral officials but by activists and sympathisers of all the parties (there were then, at most, a dozen neutral South Africans). Until a week before, the Inkatha Freedom Party refused to participate, an ever-present threat to the election: after it joined, no questions were asked about how the election was run in its strongholds.

(The IFP entered so late that it could be included only by attaching a sticker to the ballot paper: some stickers were not attached, propelling us into crisis mode).

All this ensured an election beset by so many problems that, by the time the count began, our desks were piled with allegations of wrongdoing by all major parties – the ANC, NP and IFP.

Each had loyalists who were accused of using their position as election officials to influence the result. Given the sheer volume of complaints, a result accepted by everyone seemed impossible.

The problems worsened when the results began to appear. At one point, computer hackers were detected adding votes to the NP and right-wing parties. Once that was stopped, the count became increasingly implausible – in some places, 800 percent more people than the estimated adult population voted: the three major parties accused each other of cheating.

The IEC’s staff quickly began to polarise: people who days earlier had been engaged in a common task quickly reverted to their pre-IEC identities and rallied behind their parties.

Again, a result accepted by all seemed impossible.

The first inkling of a rescue came when areas of the IEC building were closed to staff – because, we were told, senior officials of the major parties were meeting there.

The second came when the commission seemed to lose interest in our reports: I recall telling a senior commissioner that we had found more problems in the results – he looked distracted and responded as if he was being told that dinner was delayed.

From then on, the commission did not ask us for analysis.

Why? Surely because the election’s fate was no longer in the IEC’s hands: the party negotiators were bargaining the result. Certainly, the figures which magically appeared were convenient.

The ANC won but did not receive the two-thirds majority which would allow it to write a new constitution. The NP achieved just over 20 percent and so was entitled to a deputy president.

The IFP won KwaZulu-Natal.

All the parties’ complaints against each other instantly melted away.

This outcome seemed scripted by academics who had argued beforehand that we would have peace only if there was something in the result for all major parties.

In reality, it must have been bargained by the parties.

What were the “real” results? No one will ever know: the circumstances made it impossible to figure out an accurate result.

The election was saved because all three parties had grievances against each other – so there were no clear “good” or “bad” guys – and because all knew that the alternative to a deal was a conflict which could have become a civil war.

The 1994 ballot was a technical disaster but a political triumph.

Its technical failings meant that it did not produce an accurate result: but it did yield an outcome with which all could live and which made change possible.

So it may be a model for us after all – for it shows that, in this society, working out compromises may well be much more important than getting the technicalities right.

In summary, the election of 1994 was a sham — it may have undercounted black votes, or overcounted them, but the final result was calibrated as carefully as possible to remove the possibility of either black or white violence. Had the ANC won too much of the vote, it could have immediately instituted affirmative action, or communistic reforms similar to those by Robert Mugabe. With the threat of black racial communism imminent, civil war would have become inevitable. On the other hand, if the conservative parties won a majority, the sanctions would have continued and South Africa would have remained an international pariah — which would be bad for business.

If the election was a sham, why didn’t the military step in? Paramilitary groups seemed on the verge of conflict during the 1994 Bophuthatswana Crisis. The key player here was Constand Viljoen, who commanded the bulk of the paramilitary muscle. In 1980, he was appointed Chief of the South African Defence Force. By 1994, he controlled up to 60,000 paramilitary members. By comparison, the official armed forces of South African only has around 70,000 active duty members (2021). Had Viljoen given the command to rebel, he likely would have won over many members of the established military command. Rather than fighting Viljoen, many of the officers would have likely joined him in crushing the ANC in what may have become a bloody civil war.

Instead of rising up, Viljoen stood down. Whatever Viljoen’s motives, he was hailed as hero for almost single handedly stopping what seemed like an inevitable civil war. With South Africa falling apart at the seams, Viljoen’s legacy may also erode as the country falls prey to rampant crime and human suffering.

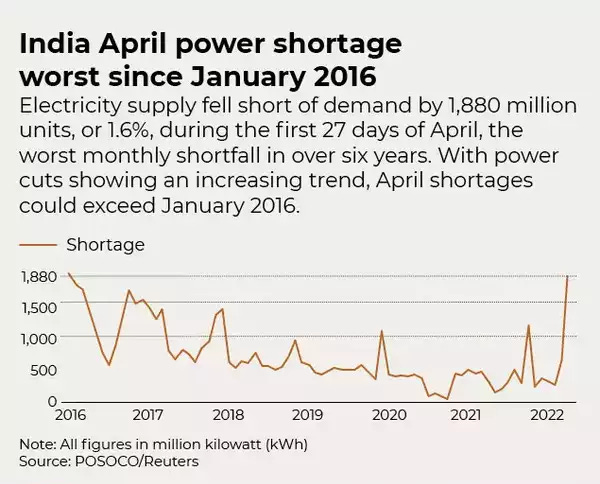

Other countries, such as India, are also struggling with increasing power outages. A future analysis compare South Africa to other countries such as India, and predict likely outcomes for America given the impact of mass immigration and continued efforts towards racial wealth redistribution.

Perhaps Obama is a foreshadow of more things to come.

https://www.npr.org/2022/05/18/1099733752/famine-africa-ukraine-invasion-drought

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Zimbabwe-Agriculture-Production-Volume-Indices-2000100_fig4_319037565

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/692638.stm

https://www.eia.gov/tools/glossary/index.php?id=reserve_margin

https://www.nerc.com/pa/RAPA/ri/Pages/PlanningReserveMargin.aspx

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921344917303282

https://www.news24.com/fin24/economy/eskoms-medupi-will-not-earn-a-financial-return-in-its-lifetime-says-funder-african-development-bank-20220602

https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/kusile-strikers-caused-r100m-in-damage--minister

https://mg.co.za/article/2013-07-24-violent-protests-erupts-at-eskoms-medupi/

https://www.news24.com/Fin24/Inside-Medupis-labour-pains-20150822

https://www.news24.com/Fin24/Inside-Medupis-labour-pains-20150822

https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/medupi-explosion-may-cost-up-to-r40bn-experts-0704c3a9-0d05-419f-9a88-845e95c87a8d

https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/kusile-strikers-caused-r100m-in-damage--minister

https://www.citizen.co.za/news/five-more-pylons-collapse-in-tshwane/

Statement on the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, October 2, 1986.

https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/South-Africa/foreign_aid/

https://billionaires.africa/2024/02/05/south-african-executive-fleetwood-grobler-pockets-2-1-million-salary-in-2023/

These quotes are taken from: Public Procurement in the Context of Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) in South Africa—Lessons Learned for Sustainable Public Procurement. Lerato Shai, Comfort Molefinyana and, Geo Quinot. Link: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/24/7164

https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/24/7164

Friedman, Steven. 2014. "The Bargain that Saved us in 1994." Sunday Independent, April 27. Previously found here: https://www.iol.co.za/the-bargain-that-saved-us-in-1994-1.1680948

Now found here: https://web.archive.org/web/20181107105826/https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/the-bargain-that-saved-us-in-1994-1680948

I reprint the entire statement here due to its near destruction, in the hopes that it will be replicated far and wide.