There are many critiques of GDP as a measurement:

GDP cannot capture every facet of human life. Qatar has a higher GDP per capita ($80k) than Denmark ($68k), but would you rather live in Qatar or Denmark?

GDP does not account for income distribution. A single billionaire and 100,000 dirt-eating slaves would have the same GDP per capita as a country where everyone makes $10,000 per year.

GDP does not measure long-term sustainability. If America opened its borders to 800+ million people, and each immigrant made $10,000 a year on average, that would increase GDP by $8 trillion. However, there would be a shock to the housing market, sewage and waste management, cultural tensions, crime, and political chaos.

GDP doesn’t measure externalities. If a $10,000 car releases PFAS, mercury, and lead into the water supply, it adds $10,000 to the GDP. Economists do not go back and revise GDP numbers downward to account for subsequent damages. To the extent that damages are measured in lawsuits, damages assessed raise GDP. Removing environmental and pollution regulations would boost GDP, but GDP doesn’t capture the cost to human health.

GDP measures medical expenses as “products.” The expense of cancer treatment increases GDP. The cost of triple bypass surgery increases GDP. When people become sick and purchase medical services they wouldn’t otherwise if they were healthy, this increases GDP. In the counter-factual where they never got sick in the first place, that would lower GDP.1 This doesn’t mean that there is a conspiracy to make people sick, but that measures of GDP can include broken windows.

GDP does not measure military strength. Iceland has a GDP of $31 billion; Houthi-controlled Yemen has a GDP of $18 billion. But considering that Yemen has a population 100x that of Iceland’s, and the average Yemeni is 18 years old while the average Icelander is 36, Yemen would be much harder to conquer by military invasion than Iceland.

Compare Russia vs Italy: while Italy’s GDP is 10% higher than Russia’s, it also has a smaller population, a slightly older population (46 vs 40), a smaller military budget ($34 vs $145 billion), no hydrocarbons, and no nuclear weapons.2 GDP doesn’t capture these differences.

GDP does not measure birth rate. There are many ways to raise the birth rate, like banning women from reading or paying women to have kids. These measures temporarily reduce the size of the workforce (pregnant and nursing women can’t work) and increase taxation (to pay for birth subsidies). Reducing pregnancies increases GDP, but without a healthy population pyramid, this leads in the long term to a high dependency ratio.

GDP does not measure religiousness or patriotism. Shipping jobs overseas, mass immigration, and secularization are all correlated with GDP.3 However, if there is a major crisis such as a war or depression, money cannot buy national cohesion. During the 1400s, Italy had the highest GDP in Europe, and yet was divided. Despite being the greatest naval power of the 15th century and the richest country per capita in 1492, Italy played no role in the colonization of the Americas, Africa, Asia, or the Middle East.4 With more political cohesion, Italy would have been able to collectively pool investment for colonization.5 But GDP doesn’t measure political unity.

GDP doesn’t measure trust. Trust in institutions is a vital measurement of state resilience. When times are good, trust is not so important. But if the country is under attack, corrupt and cynical officers can be bought off, as in Iran.

GDP doesn’t measure genetics. Genetics is the foundation of wealth. The modern world contains unprecedented threats to genetic integrity. If genetic health is sacrificed in exchange for GDP, this is like using performance enhancing drugs. It looks great at first, until the effects catch up years down the line.

GDP doesn’t measure ethnic, religious, ideological or racial diversity. During the Winter War, the Finnish nation came together to resist communist aggression. Meanwhile, Stalin was conducting mass deportations of six million ethnic minorities who opposed his rule. Even if diversity is a good thing in peaceful situations, it can be a source of tension and political disunity in times of crisis and war.

Now that we have these critiques out of the way (leave some more in the comments below), I’d like to defend why GDP is still a useful measurement. Even if you’re concerned about the above issues, ignoring or dismissing GDP is not an intelligent way to design policy.

GDP is like IQ

Many of the same arguments that the mainstream left uses against IQ are rehashed and recycled by right-wing nationalists when it comes to GDP.

It doesn’t measure everything!

It’s an imperfect measure!

It cannot capture every facet of the human experience!

There’s more to life than IQ/GDP!

These statements are all true, but they are all forms of tactical epistemic nihilism.

Consistent epistemic nihilism would dismiss all sociological, political, and economic measures as imperfect, incomplete, insufficient, and one-dimensional. Whether we’re talking about GDP, IQ, testosterone levels, lifespan, inequality, poverty, grip strength, body count, sperm count, or any other measurement, none of these numbers in isolation can provide a complete picture of any society. Even if you’re religious, a simple headcount of self-identified theists isn’t a good measure of national virtue; there is always qualitative data to drill down into.

GDP and IQ aren’t specific measures; quite the opposite. They are meta-measures which combine together a broad spectrum of composite data. GDP doesn’t measure one thing, and neither does IQ. When facing a particular crisis, a country’s GDP or national IQ alone might not be sufficient to determine success. As we drill down to the level of individuals, measurements of wealth and intelligence become less predictive of outcomes.

But just because a single number doesn’t give us the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything doesn’t mean that number is useless.

Epistemic nihilists are not consistent; they are tactical hypocrites. They accept the validity of some measures, when it benefits their narrative, but not others. When a number is inconvenient to their “lived experience,” that number is subjected to endless scrutiny and what-aboutism.

Is Everything Getting Worse?

Regressive socialists and the dissident right believe that America in 1940 was a unionist paradise where every man was a king. Healthcare was free, housing was cheap, and the working man commanded respect, supporting his family of four on a single income. Now, we live in pods, eat bugs, charge our phones, be bisexual, eat hot chip, and lie.

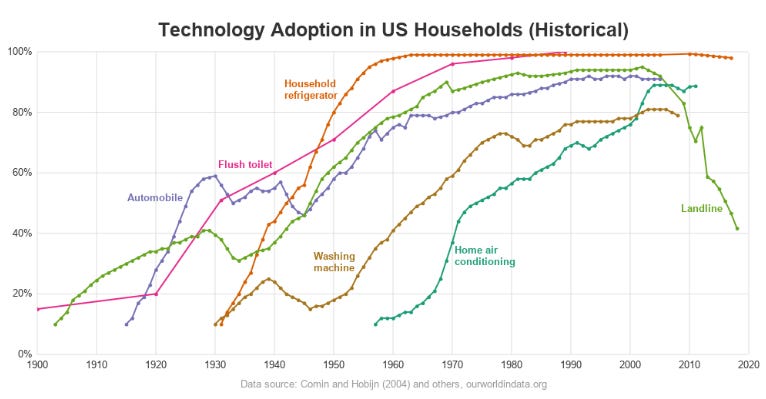

The problem with this narrative is that there is nothing preventing anyone from living like an Amish person and returning to the glory days of the 1940s. They live in smaller houses with no air conditioning, no flush toilets, no washing machines, no cellphones, and no TV, and can easily afford to support 8 kids!

Americans choose to have bigger houses, modern plumbing, refrigeration, climate control, and HD streaming, and then complain that they can’t afford to have kids. They make this argument compulsively and unthinkingly. No matter how many times you tell these people that their great grandparents had it much worse, and still had many more children, they will stare at you blankly and continue to repeat the same talking points, over and over. It isn’t that we’ve become poorer; it’s that we’ve changed our values, our religion, our priorities, and our willingness to sacrifice comfort in exchange for family life.

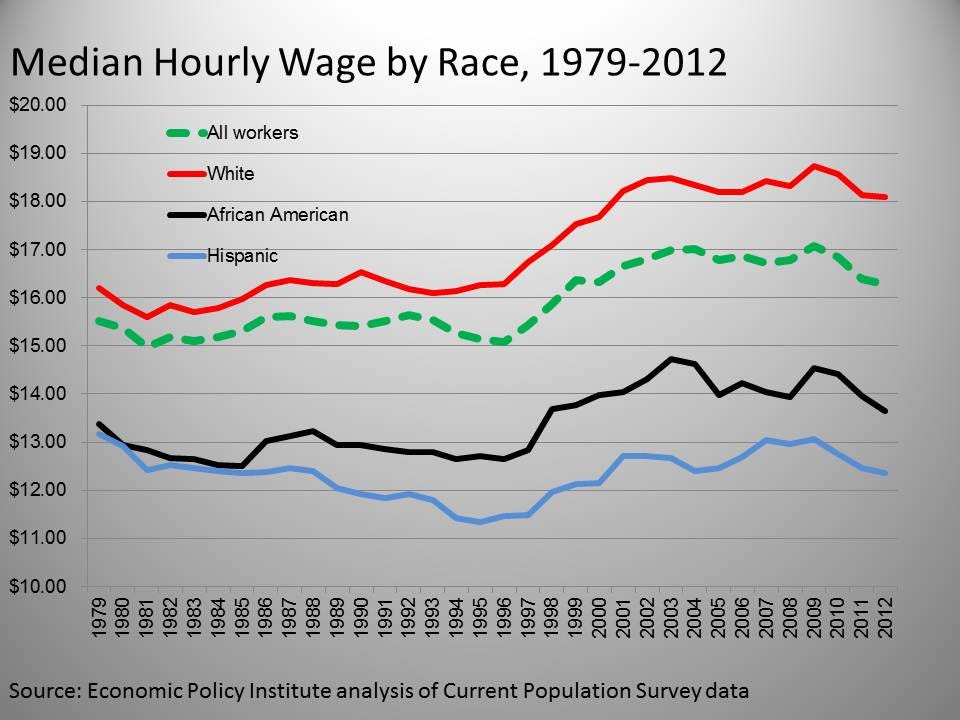

For the left, the supposed “decline in living standards” isn’t without some compensation in the form of rights for women and minorities. But for the dissident right, this compensation only worsens the balance sheet. Ironically, from a racialist perspective, white Americans have benefitted much more from globalization than non-whites.

Income inequality and stagnating wages aren’t as bad when non-whites are excluded. Sometimes racialists argue that “non-whites are responsible for stagnating wages.” What does that mean? If non-whites are driving down wages, that means that white wages must be increasing. If non-whites are poor, and the country becomes less white, then stagnant wages necessitate an increase in white wages.

From 1979 to 2012, the Hispanic population increased from 8 million to 53 million. Over the same period, Hispanic wages remained stagnant, lower than black wages. The influx of Hispanic workers depressed the median wage, but it had no suppressant effect on the median white wage.

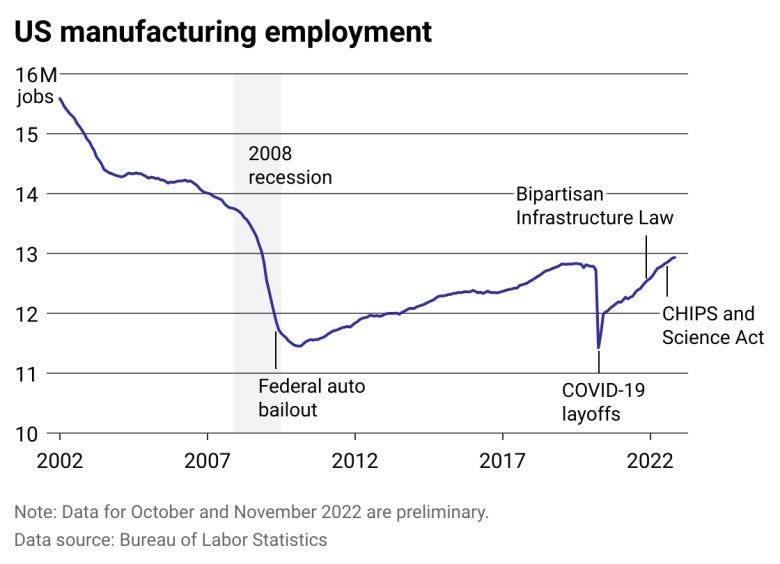

The dissident right believes that wages are falling due to globalization. They stole this talking point from 1990s leftists, so maybe we should call this talking point “dissident leftism.” According to the dissident leftist thesis, America imported cheap labor and shipped all the manufacturing jobs to China. This killed the American middle class, who had no recourse but to overdose on drugs.

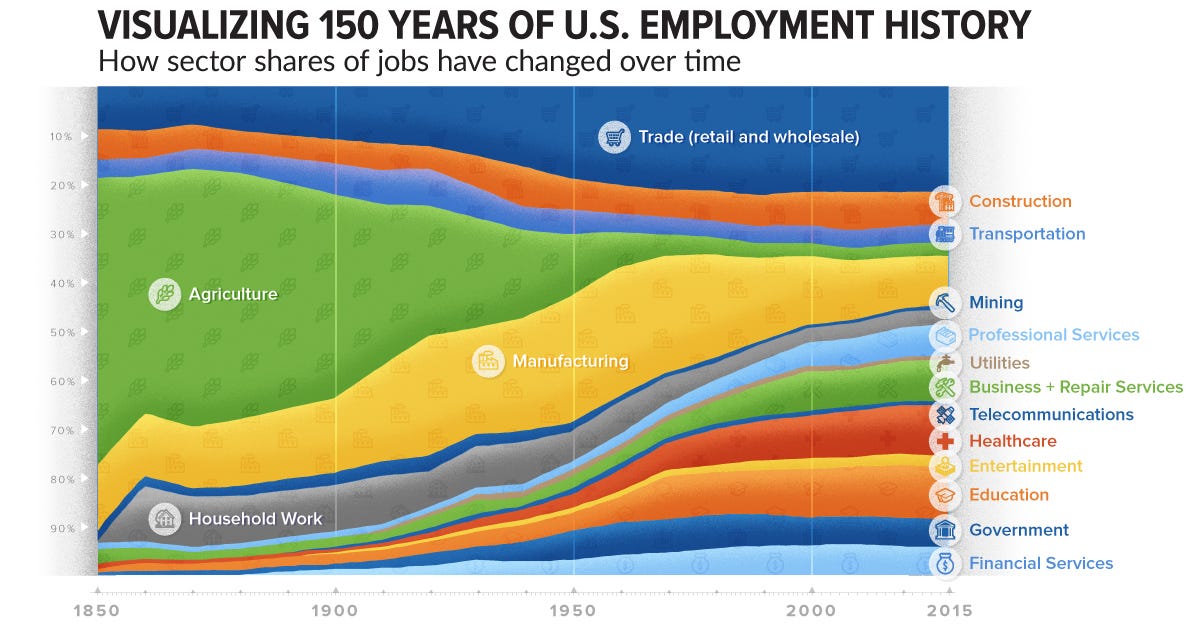

In reality, outsourcing basically stopped in 2010, when the number of manufacturing jobs stopped declining despite increases in automation. In fact, if we zoom in, we can see an increase in manufacturing jobs since 2010.

Contrary to the narrative that outsourcing is driving middle class whites into poverty, a history of wage increases shows the years 1996 to 2003 as the period of greatest increase since 1979. But it was that same exact period when manufacturing was undergoing its greatest decline. Instead of whites being forced out of the factories into poverty, they got higher wage jobs in other industries.

The American auto worker isn’t competing with the Chinese worker with tiny nimble hands; he is competing with a robot arm. Automation has made Americans richer.

There are some Americans who have suffered from the loss of manufacturing jobs because they have low intelligence. They do not have the cognitive capacity to do much more than repetitively assembling chicken nuggets on a conveyor belt. If you’re on the left, you might support giving these people greater access to education, training, or welfare. But trying to bring back their jobs by regulating technology and restricting trade undermines the productivity of intelligent Americans. It punishes America’s productive class for being smart in order to shelter and coddle those left behind.

What about education?

Intelligent critiques of GDP do not dispute that Americans have become wealthier. According to Sebjenseb’s comparison of 1950 to 2025, the problem isn’t a decline in wealth, but a decline in education, dating, and political culture.

On dating and political culture, I agree that these are factors which are not captured by GDP and are definitely worrying. It’s not possible to capture the number of fake sex scandals, the loneliness crisis, populism, or polarization with GDP.

I like Matt Yglesias and Noah Smith, but the rosy view of American progress is incomplete without an honest assessment of these problems. There may be some ways in which social isolation and sexual dysfunction have positive externalities, but sociologically, these things suck. I would be happy to trade some GDP in favor of suppressing some populist craziness on the global stage.6

The political culture of the 1950s, with elite consensus between Democrats and Republicans on most issues of social and foreign policy, seems idyllic compared to what we have now.

One area where I would push back on Sebjenseb’s assessment is education. It is true that education has become less efficient — we spend more, and obtain the same (or worse) test scores. But when controlling for race, the picture improves. Education spending rose from 1% to 8% of GDP, but the purpose of that increase isn’t improving cognition, but compensating for a loss of social cohesion.

The Cathedral

In 1910, most Americans went to church, and this provided them with a sense of lifelong structure, morality, and purpose that transcended transactional wage labor. The education system today is designed to mirror and replace the church, hence “the cathedral.” It may be doing so poorly and inefficiently, and perhaps its morals and values are destructive, but that is the intention.

The goals of the American educational system are not domestic, they are global. Just as the Papacy’s budget isn’t just meant to cover Vatican City, American spending on education is meant to provide global solutions to global problems. Harvard is the American Vatican.

The American education system is a globalist plot to take over the world, not merely a domestic project. Its scale and scope includes American client states, like Great Britain. This is why America has more foreign students than any other country in the world.

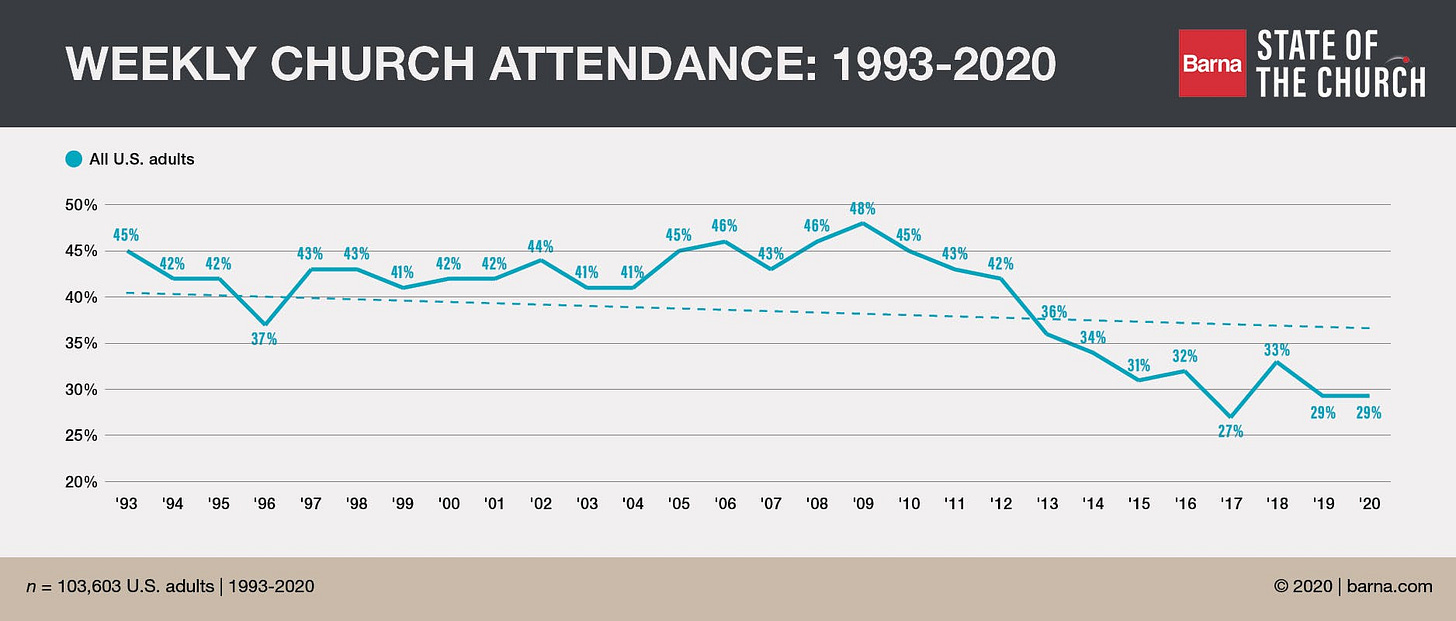

When assessing the decline of religion in the western world, we have to look beyond the mere headcount of church attendance. If people are attending a qualitatively weaker church, then church attendance becomes less meaningful. In Ryan Burge’s study of religious denominations, he found that less than 24% of mainline Protestant pastors believe that Adam was a real person; less than 45% believe in hell. Remember, these are the pastors who devote their lives to the church, not the parishioners who are dragged there by their families.

If the leaders of the church don’t even believe in their own religion, then the amount of authority and certainty that can be derived from that institution is weak. The result of this weakness is that other sources of authority, like academia, are attempting to pick up the slack and provide some sense of moral structure in the form of a civil religion.

Weekly church attendance hasn’t fallen by much, but the percentage of people never attending services has risen dramatically.

Regarding the qualitative decline in churches, Ryan Burge’s data also shows that church is no longer a pro-social force in the way it used to be. Historically, those who went to church were more trusting of strangers. Now, those who go to church are more suspicious of strangers than those who do not attend. While religion used to unite Americans and give them a sense of unity, it now divides Americans and feeds polarization.

There is no easy solution to this problem. Libertarians would prefer we slash the education budget and let the chips fall where they may. Fascists would prefer we redirect that spending toward “patriotic education.” The liberal bloating of education is an attempt to fill the vacuum left by the death of Christianity. If we consider the education system as a state religion, then spending 8% is in-line with historical tithing on religious institutions.

In Victorian England, as the old aristocracy was flooded with a new secular and mercantile elite, the upper class attempted to navigate this “ordeal of civility” by creating a Byzantine series of rules called “manners” to govern all social interactions. Pinkies up!

The extreme manners of Victorian England seems artificial and stilted because they were an attempt to mediate a period of nihilism, “an age without values.” For conservatives, suggesting that the 1800s were an “age without values” seems ridiculous, but when seen in the light of the changing class structure and the philosophical challenges to Christian theology, the claim becomes stronger. Any time the ruling class becomes obsessed with manners and politeness, that is a sign of nihilism.

Wokeness and political correctness lack the aesthetics of the Victorian era (no pinkies), but sociologically, they serve the same function. The crisis of authority is a problem; the libertarian approach of cutting the budget and hoping everything works out on its own is not a sustainable course. All states are theocracies — even secular ones like the CCP or North Korea. States which fail to develop powerful theocracies end up corrupt and fragile.

One could criticize Iran as being less theocratic than America: there are probably more true believers in wokeness in America than there are Shiite clerics in Iran. Democrats have been winning 40% of the vote since 1964; I’m not sure the clerics in Iran could achieve that level of support in a free and fair election. If you cut out blacks, Asians, and Hispanics, and focus only on wealthy whites, there is still sufficient faith in “the system” to support this thesis. If we reduced our education spending from 8% to 1%, this level of support would probably fall.7

It’s true that we spend more on education today than we did in the 1950s, but the pressures and demands on our education system to provide a global theocratic structure are much greater today than they were in 1950. The priest class has a way of bloating their own budget, which is basically unavoidable. Medieval priests probably didn’t need that 10% tithe, but there are limits to the efficiency of a priest class.

While it’s true that education is more expensive today, since Americans are wealthier, on net, it really doesn’t matter. The question of whether America was better in 1950 vs 2025 should look at the net sum of wages and taxes. If education is a tax, and we subtract it from wages, and the wages are still higher today than they were in 1950, the net effect is positive.

Education costs are concentrated on women and midwits. Smart students can get a scholarship, or get a good enough job to quickly pay off loans. Among white men, only the bottom 30% have financial troubles after graduation. Insolvency is concentrated among women, with ~70% black women struggling to pay their loans. Student loans are not a white man’s burden; they are a black woman’s burden.

The other defense of the education budget is that when it comes to research, a bloated budget is better than a lean one. For the purposes of bulking, a candy bar with 10 grams of protein is better than 1 gram of protein powder. It is better to have a budget which is bloated and inefficient than a budget which is efficient but too small.

American universities still dominate the globe, or else Indians and Chinese wouldn’t be jumping over each other to come here. American education is the worst system, except for all the rest. If American education were really so bad, Americans would be flocking to Beijing, rather than the other way around.8

Conclusion.

Are white men worse off in 2025 than in 1950? It depends on which white men you’re talking about, and in what respect. If you’re a college graduate who attends the Mormon church weekly, your chances of overdosing on opioids is slim to none. If you’re a 90 IQ college dropout with tattoos who smokes weed in his mom’s basement, those chances increase exponentially.

For people who are unable to cognitively advance past repetitive assembly line work, the decline of manufacturing jobs has been a negative phenomenon. However, this development would have occurred without outsourcing or immigrants. Even if outsourcing to China never occurred, and immigrants never came into the country, automation still would have displaced low-skilled workers.

With that said, even if low-skilled labor is declining, death by opioids is more a function of a lack of religiousness than lack of money. It could be argued that without the suppressing effects of prohibition, deaths of despair in 1920 would have exceeded current numbers.

The problem with arguing that opioid deaths are only a result of poverty is that they are unusually high in Massachusetts, which is not exactly the rust belt. Compare Massachusetts to Alabama and Mississippi, and it becomes even more difficult to argue that poverty is the cause.

The common thread between Massachusetts and West Virginia is that these are both areas where mainline churches (as opposed to Southern Baptists and Evangelicals) were the historical support structure. Since young male attendance in mainline churches has evaporated, this creates the conditions for opioid dependence. To get young men off drugs, get them back in church or into higher education. Outsourcing and immigration are not good explanations.

There are plenty of things that matter besides GDP: stability, unity, health, safety, trust, birth rate, equality, and sustainability. One of the lies told by the GDP-critical crowd is that all of these things are mutually exclusive with GDP.

The greatest amount of oceanic pollution in the world is produced by India and the Philippines, not the developed world. Poor countries tend to have more corruption and less trust in government. Many of the factors which make a military strong also help to structure an economy: efficiency, meritocracy, and honesty. We don’t always have to choose one or the other. In many cases, while GDP doesn’t fully capture all good things, it does correlate with many of them.

There are still cases where it is preferable to sacrifice some GDP in exchange for something else. Maintaining a global security system is expensive, but worth it in terms of the long term returns in trade. Pollution is difficult to regulate, but the risks to human health outweigh the losses in industrial production. Education is cumbersome and bloated, but it’s better to have institutions which support research and social cohesion than allowing society to disintegrate in the name of “government efficiency.”

The purpose of the human species is not the pursuit of wealth. Wealth is a means to an end, which is to gain control of our genetic destiny. That’s the story of biological life — genetic evolution, not the pursuit of happiness or the collection of baubles and trinkets.

Economic surplus enables us to advance genetic science. Quarterly financial reports may not be exciting or life affirming, but the arc of technological progress bends toward a genetic revolution. Beyond that threshold, we can escape the sclerosis of the current age and rediscover the adventure of life.

The counter-argument is that a healthier country would probably produce more stuff in the end, but I’m including this argument because it is logically plausible, not because it’s empirically true.

Interestingly, Italian industrial production is actually equal to Russian industrial production.

This is a chicken or egg situation, since poor countries can’t afford to ship industry overseas and are not attractive to immigrants. Possibly a feedback loop.

Columbus went to Spain seeking investment.

Some nationalists claim that colonialism was a net detriment for various empires. This may be true for the French or Spanish. In the case of the British, America has been an indispensable ally in preventing the German takeover of Europe. Nationalists who argue that America and Britain are not the same nation are playing a shell game where they selectively switch between civic and racial nationalism when it suits them. The Roman Empire was Italy’s ancient colonial project. Nothing lasts forever.

This is why I support Democrats, who I believe have a saner, more credible, and pro-American policy of restraint in the Middle East, while supporting the stability of our long-standing alliances in Ukraine. On dating, neither party has very good policies, since Republicans do nothing to resist Nancy Mace feminism.

I would support reducing spending to 4% and redirecting the other 4% to pure research, but that’s still 4x as much spending as we did back in 1910.

One reasonable critique of the education system is that we send too many people to college. Sending 60% of the population to college does seem excessive.

Gee Dee Pee!

Gee Dee Pee!

I like these analyses. The problem I have with a number of economic concepts such as GDP, economic growth, and "money" itself is how far removed they are from what I think really matters: matter (especially food and shelter) and energy (which enables everything to work). GDP isn't a totally useless concept; it is just incredibly indirect. I could say that money isn't a totally useless concept, because at this moment I can trade money in my bank account for material goods I use to survive and energy to make my car and appliances run. But that could change in a moment, if suddenly the world refused to acknowledge the value of the figures in my bank account.

Increasing numbers in my bank account seem to indicate progress. But fiscal figures only indicate a promise that may or may not be fulfilled. What if 10 people promised me $100,000 each--would I suddenly be a millionaire? I would not count on it.

In the marketplace, economists speak of economic progress in terms of increasing rates of economic transactions that lead to an increase of GDP. But simply increasing the manufacturing and selling of things does not mean we are better off. Are the products truly useful, helping to keep us alive and gain control of our genetic destiny? Or are we just accumulating tchotchkes that clutter up our houses?

For me, a strong indicator of economic progress is our ability to extract energy with less work. It takes a lot of work to extract fossil fuels from the ground, refine them, and distribute them. That's why I sense that improving our ability to use the sun for energy will lead to genuine economic progress. If we could only figure out how to incorporate chlorophyll into our skin to extract energy from the sun instead of hunting, fishing, growing, distributing, storing, and cooking what we currently use to fuel our bodies, we would really be on the road to economic progress.