The primary unit of human action is the state. All states begin as theocracies, and separation between church and state only occurs only once the state bureaucracy is sufficiently developed. This separation is not linear, but cyclical.

The Catholic Church insisted on its independence from Henry VIII; Henry responded by attempting to reintegrate the church with the state. Cromwell attempted to finalize this integration, and the Boston Revolt of 1689 was a parallel attempt to establish a sovereign Puritan theocracy.

The period before Luther was a period of radical division between church and state. According to Machiavelli, the Catholic church was not integrated with any state, but was itself a separate and independent state, with its own military, interests, and conflicts. This lack of integration between church and state was noted by Machiavelli as a major source of cynicism, corruption, distrust, and disharmony.

The separation between church and state was first initiated in the medieval period by Gregory VII, who sought to separate Emperor Heinrich of Germany from his church, and revoke his power to appoint bishops.

The power of kings to appoint bishops had been respected since Emperor Constantine, who appointed Julius I (the Pope!) to be bishop of Rome. Three centuries later, King Ethelbert of Kent, a convert (!), appointed Mellitus as bishop of London. When Gregory VII decided to revoke this established right from Heinrich IV, he was overturning 739 years of precedent. It was at this point, in 1076, that a medieval split between church and state first occurred. It was not initiated by the secular powers, but by the spiritual ones.

Calvin, Cromwell, and the Puritans sought to reintegrate the church and state. They were not entirely successful, and Catholicism persisted in various forms throughout the British Empire.

Following the failure to integrate the state with the Protestant religion, a parallel religious form arose in the 16th century: secular nationalism. Nationalism was the new religion which would unify the state. It was resisted by the recalcitrant aristocracy, which by that time ceased to be a genuine warrior class, and instead consisted of hereditary land speculation. Such classes were eventually overcome by secular nationalists.

The first forms of nationalism far precede the French, English, or Americans. If we want to find the secular roots of nationalism, we have to look toward the Dutch. The Dutch, like the French and English, were deeply involved in early Freemasonry, which would later finance the Dutch East India Company (1602). The Dutch invented the concept of religious tolerance, preceding the First Amendment by 212 years. The edict of toleration of The Union of Utrecht was signed in 1579, and it attracted Sephardic Jews to Amsterdam, like the family of famous philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

Fast forwarding to the 19th century, Napoleon’s military was defeated, but his ideas were not. Napoleonic nationalism led to the reordering of Europe on ethnic lines. Germany and Italy were founded as ethno-nationalist states by Freemasons and leftists. For an explanation as to how leftism and nationalism cooperated, although they are today enemies, see my article on the stages of nationalism.

By the 20th century, nationalism reigned supreme over Europe and America, and this new religious form allowed for European and American powers to conquer the entire world. It became so powerful that it was now ready to supplant and exterminate Christianity entirely.

Spiritual nationalism, which loosely encompasses both the philosophy of Mussolini and Hitler, is often referred to as fascism. The word fascist is both too broad and too narrow, and is now used as a political slur against Trump rather than as a term of political science. The fact that Democrats are not engaging in a violent war against Trump proves that they are hypocrites in this regard.

In the aftermath of the First World War, General Ludendorff wrote his memoirs, which include a call for the nation, rather than church, to be the center of spiritual struggle. Very soon afterward, he abandoned the church entirely. His personal development signaled the death of Christianity as a significant force in Europe. This process had been brewing for hundreds of years (one could say since the toleration of Utrecht), but it had finally reached a tipping point and broken into public consciousness.

Christianity was very quickly replaced by one of two forces: communism or spiritual nationalism. These ideologies were “totalitarian,” because of their lack of democracy, no separation of powers, no parliament, no constitution, no rule of law, no free speech, no right to due process, and so on.

Technically, a theocratic state could sacralized voting, have three separate branches of government, with aspects of democracy, a parliament of aristocrats (a senate), a constitution (a Bible), rule of law, some degree of freedom of speech on non-religious matters, and a right to trial by jury. If a state guaranteed all these rights, it would not be totalitarian, but it could still be theocratic or integralist. Early colonial governments, especially the Massachusetts Bay Colony, could rightly be called Constitutional Theocracies, rather than totalitarian ones. The Roman Republic and the Democracy of Athens also had state religions, but guaranteed the rights of citizens to their property. Integralism is not necessarily totalitarianism.

totalitarian secular integralism.

Imagine that, after the death of Stalin or Hitler, some kind of government had been set up which then worshipped the dead dictator as a God. In the Soviet Union, this process was disrupted by Khrushchev (among others), in part because Stalin failed to appoint a successor. Stalin’s favor successor was this Pillsbury doughboy, Malenkov, who failed to hold onto power:

The model of communist hereditary monarchy has worked quite well in North Korea. In China, there is a mixed model, where leaders are appointed rather than born. Communism provides a model of integralism, where the state has total authority over moral and spiritual matters.

Hitler lost the war, but his subordinates had plans to replace Christianity:

First, as a transitional form, the Nazis created positives Christentum, in which all priests were forced to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler.

Second, Alfred Rosenberg wrote Der Mythus des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts as a theological document to provide the basis for a new religion.

Third, Himmler abolished Christianity from within the Schutzstaffel, and required that SS officers were married with a ceremony which included readings from Nietzsche, rather than from the Bible.

The Nazis did not take these reforms further because of the fear of conflict. This fear was warranted, because all of the assassination attempts against Hitler were planned by Christians, and it was Christians like General Paulus and Admiral Canaris who defied Hitler’s orders. Further antagonism would have resulted in a successful assassination and more numerous and brazen forms of sabotage, or perhaps a successful coup and civil war.

Had the Nazi state survived the war, it would have increased persecution of Christians and expanded the growing corpus of non-Christian “spiritual nationalist” religious literature.

I mention these examples not to glorify or hold them up as ideals of “what could have been,” but instead to demonstrate that all of the world powers were headed toward integralism. The western powers were the least outwardly integralist in their approach. However, in a revisionist approach to the 1940s, we can see how even western Democracies were undergoing a religious revolution away from Christianity, parallel to both Naziism and communism. As a result leftism emerged as the new and preferred religious form among academia, the western priest class.

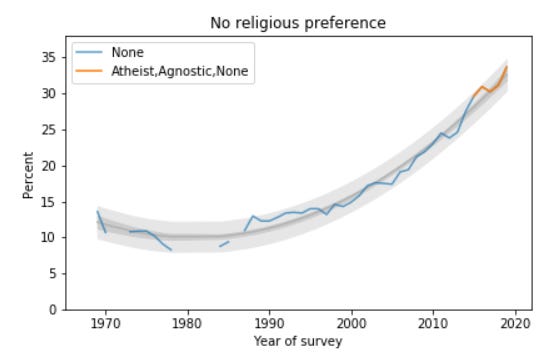

The speed of the atheist revolution:

It is difficult to estimate the speed and progress of this transition. According to Harvard Magazine in 2007,

Although nearly 37 percent of professors at elite research schools like Harvard are atheist or agnostic, about 20 percent of their colleagues have “no doubt that God exists.”

It is difficult to find historical data on this question. However, it can be inferred.

A survey from 2010 found that,

While atheists and agnostics in the United States make up about 3 and 4.1 percent [7.1% total] of the population, respectively, the prevalence of atheism and agnosticism was much higher among professors: 9.8 percent of professors chose the statement, “I don't believe in God,” while another 13.1 percent chose, “I don't know whether there is a God.” [22.9% total]

Church attendance among students has dropped from 92% to 1969 to 66% in 2019, which is a decline of 26% over 50 years, or roughly 0.5% per year. The decline has not been linear, but has increased exponentially since after 2000.

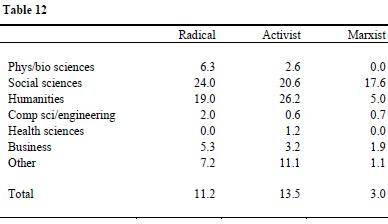

A survey of professors in 2006 found that 11.2% were self-identified “political radicals,” with that number increasing to 24% in the social sciences. This is consistent with the finding that psychology professors are twice as likely as other professors to be atheist/agnostic. They constitute a priest class who are more advanced or logically consistent in their rejection of Christianity, and their radicalism is a product of their need to fill the void.

It is also pertinent to note that, among believers, the normativity of Protestantism decreased dramatically between 1930 and 1971. In 1971, 79% of the oldest professors were Protestant, while only 60.7% of the incoming professors were Protestants, representing a decline of 18.3% over roughly 41 years.1

This dramatic shift represents both the result of immigration and the relaxation of WASP affirmative action. Prior to 1930, it was very difficult for Jews or Catholics to become professors, even if they were qualified. This is because students of a Jewish or Catholic background were often excluded from enrollment, and those who did graduate were excluded again from being hired as professors.

In the 1900s, America was only 68% Protestant, but the professoriate was well over 80% Protestant. By 1971, America was less than 52% Protestant, but Protestants still made up 60.7% of incoming professors. This represents a “three decade lag” in demographic terms.

By extrapolating from existing data, the expected value for professors who were atheist/agnostic in 1969 (5.4%) matches closely with the recorded value from the American Jewish Year Book, of 6.1% for 1971.

Older professors (35-44) were the most “other & none” at 8.1%, rather than the youngest ones. This implies that there was a spike in political or religious radicalism in the 1940s, which actually died down by 1971.

This crop of professors was influenced by the Beatniks, Norman Mailer (first published 1948), and Allen Ginsberg (famous in 1956). The idea that the 1960s was a unique and sudden phenomenon is contradicted by the data.

The youngest professor in 1920 was Tolkien at age 28. Isaac Asimov became a professor at age 29. Therefore, the American Jewish Year Book data, when speaking of “professoriate,” is probably also including grad students, research assistants, and other “faculty.” For the purposes of this projection, we will assume that became “faculty” at the age of 25, although it could have been much later.

As such, when the 1971 study shows “65 years and over,” we will interpret that as “became a student in 1925.” This isn’t entirely accurate, because people become students and professors at different ages. The point is to roughly track the age at which professors first became students, and to project backwards the radicalism of that period.

The picture that emerges is not one of the radical 1960s, but of 1945 as the height of radical change and activism. The 1940s should be thought of as a period of communism, atheism, and religious revolution in America. It was during this period that American elites began to pass legislation against racism.

The 1960s were a relatively tame “kinetic release” of the built up potential of the 1940s. Students during the 1940s became professors by the 1960s, and taught their students to be communist radicals, which resulted in the sexual revolution, Vietnam protests, Flower Power, and later, the bombing campaign of the Weather Underground.

Rather than seeing the Nazis and communists as the only radical revolutionaries of the 1940s, western democracies must also be considered as having undergone a revolution during this period, albeit one that only became apparent to the general public in the 1960s. The repression of atheism in the 1960s may have been due to the activism of the Campus Crusade, founded in 1951.

Although the Nazi revolution, communist revolution, and woke revolution of the 1940s were all different in their aims, goals, and ideals, what they shared was an opposition to traditional Christianity and a desire to replace it with a new vision for humanity. While communism and Naziism both failed in Europe, communism did successfully persist in some form in China.2

measuring integralism:

I will graph confidence in religion, or integralism, for the last 2,900 years of western civilization. Reducing this to a singular number is an oversimplification because of the diversity of western cultures. Here is my crude methodology:

1. classical period:

The Greek Dark Ages (1200-700 BC) were a time of chaos, out of which Homer and Hesiod wrote the first European theology. Pindar celebrates the first Olympic games, and Athenian Democracy is founded afterwards, at the height of the Greek Golden Age (500 BC).

Greece began to decline into “atheism,” a lack of theological integrity, with Socrates. Rome lagged behind by centuries (in the same way that American atheism lags behind European atheism).

Rome reached a low point not during the birth of Christ, but during the reign of Heliogabalus. It was thrown into 100 years of uncertainty and atheism, before Constantine appointed the first Roman Imperial bishops.

2. medieval period:

While Rome collapsed, Christianity survived and brought civilization to northern Europe. By 1000, Europe was at the height of its theological integrity.

Following the Investiture Contest, integrity began to decline, although Reformers helped keep Christianity alive in the 16th century.

3. modern period:

In the 19th century, nationalism and imperialism brought Europe to the height of global power. Concepts like White Supremacy, the Aryan Race, Eugenics, and the White Man’s Burden were broadly agreed upon by European intellectuals. These concepts would experience a crisis of confidence in 1919, and collapse violently in 1945. The period from 1848 to 1980 could be called “schizophrenic” because of the quick rise and fall of nationalist theological integrity in quick succession.

The year before the open internet, 1992, could be considered the height of Francis Fukuyama’s End of History. The Soviets were gone and America controlled the world. White Nationalism was in recession; Clinton was a moderate; centrist conservative liberalism was dominant. Since 1992, America has sharply become unmoored.

The first black president, alongside a sharp increase in pronouns, transgenderism, and trigger warnings, inspired a reactionary wave of White Nationalism. Black Lives Matter and COVID traumatized a generation.

condensed overview:

The Greek Dark Ages were chaotic, while the founding of Athenian Democracy was a period of integration.

The sacrilege of Heliogabalus was a low point for Roman religion, and the conversion of the Hungarians and Norwegians was a high point for the Catholic Church.

The Theses of Luther successfully held off a crisis through the Reformation, which led to the establishment of nationalism. In 1919, nationalism entered a crisis, with a crescendo in 1945. By 1992, American confidence peaked, but has been declining since.

2,900 years of history:

During periods of declining integralism, imperialism grew. The period between Alexander the Great and Heliogabalus saw the greatest expansion of Graeco-Roman militarism. The aftermath, however, was disastrous. The formation of the Christian religion between Constantine and the Investiture Contest was militarily stunted. Arabs, Mongols, Vikings, and Turks all threatened Europe during this period.

After the 12th century, Europe became an expansive power, launching crusades, retaking Spain, discovering America, and conquering the world. If integralism is once again in decline, we should expect this period to include military victories, like Alexander and Caesar, and discoveries, like Columbus.

Classical pagan integralism declined for 726 years, from Democracy to Heliogabalus. From trough to peak, from 218 until the Investiture Contest of 1079, was a period of 861 years.

Using the classical figure, Europe should have “bottomed out” in 1805, during Napoleon’s Battle of Austerlitz. Using the medieval figure, Europe should have “bottomed out” in 1940, the height of Naziism before its conflict with America.

Summary:

If the 1940s represent the beginning of the death of Christianity in America, then the 2040s represent the completion of that process. A majority of Americans will no longer be Christian, and Christian Zionism will be completely marginal. That’s not to say Christians will cease existing — there were, of course, pagans during the time of Constantine, and afterward. Emperors had to keep banning pagan practices through 392.

Just as the sacrilege of Heliogabalus (218) led to the conversion of Constantine (312), the period between 2045 and 2139 will be very unstable, and filled with Civil War. Yet, it will also be a period of imperial expansion. The question is, what religion will fill the void left by Christianity?

Since 1992, the defeat of Naziism and communism in the west has left a vacuum which is now being filled by racial and sexual minoritarianism. Can this minoritarianism radicalize into a totalitarian regime, as Naziism and communism did? Will it impose the death penalty for racists and sexists? Or will the right-wing wage a Civil War? Both of those seem unlikely in the near future.

What is the third option?

When Christ died, he left behind the blueprint for a new religion. It took three centuries for that religion to become accepted by the Roman aristocracy. When Darwin died in 1882, he left behind a message no less revelatory: the concept of biological evolution and the Origin of Species. Darwin’s Revolution is not over. It is only now beginning.

Religious crises never result in a decline in military power, at least until the crisis is ideologically resolved. The crisis of Caesar increased the might of Rome; and Constantine did not decrease Rome's power. However, the subsequent centuries were militarily depleted. The crisis of Protestantism did not decrease European expansion, but accelerated it. As we are entering deeper into crisis, we may see a new phase of NATO expansion, followed by an eventual religious reformation, and eventually a “dark age.” This dark age will mirror the Greek Dark Ages, in that it will provide the Iliad and Odyssey for a new civilization.

This isn’t exact, since some of the 65+ professors may have started as early as the 1920s. However, it is unlikely that there were many professors over the age of 76 who could have started teaching before that time.

It is questionable, from a Spenglerian point of view, whether or not Maoism can be considered an extension of western thought, or whether Chinese Marxism should be considered spiritually indigenous and foreign in name only. The term pseudo-morphosis seems apt.

Rome declined into atheism at around the same time Greeks did, and were arguably much worse in this regard. It’s just that Augustus made a lot of efforts to revive religion in Rome, so it lived on. Also, I wouldn’t say Socrates was the major corrupter of religion so much as the Stoics and Epicureans were, and these groups were very popular in Rome.

Edit needed: “All states begin as theocracies, and separation between church and state only occurs only once the state bureaucracy is sufficiently developed. This separation is not linear, but cyclical.”