The Critical Theory™ history of American politics goes something like this:

1776-1859: Should we own slaves?

1860-1965: Should we allow racism?

1966-2024: How much immigration?

In other words: race, race, and more race. While it’s important to highlight the importance of race in American politics, the focus on race as the only issue is slightly anachronistic. Issues like federalism, westward expansion, the gold and silver standard, tariffs, and religious freedom all played a significant role in the ideological character of America’s political parties. After all, 99% of Americans before 1954 lived in racially homogeneous neighborhoods, and their personal finances were more pressing than anything else.

Following the Civil War, America became a hotbed of socialism and unionization. The Socialist Labor Party of America was founded in 1876. The party was led by a Jewish immigrant named Daniel De Leon from 1890 to 1914. The Workingmen's Party of the United States, also founded in 1876, was led by Irish immigrant Joseph Patrick McDonnell, a collaborator with Marx. It was not unusual that these parties were founded and led by non-Protestant immigrants. The leadership of America’s early socialist and labor movements were disproportionately made up of unassimilated foreigners.

By 1888, however, Eugene Debs, a Protestant American, began to syncretize populist Anglo-Saxon culture with socialism. Huey Long’s cry, “Every Man a King!” was the logical conclusion of this process. The same process also occurred in other parts of the industrialized world. The result of this fusion was fascism in Italy, Naziism in Germany, the Labor Party in Britain, and FDR in America.

Hanania’s new article accurately points out that organized labor was never a voluntary association of workers, but only became effective through violence and government coercion. In Russia, because there was never a gradual “populist fusion” between the working class and the Bolsheviks, Marxist ideas were never made “fascist” in the way that they were in Italy and Germany. On the other hand, the Labor Party of Britain’s social liberalism, and the progressive racial attitudes of FDR, put the English-speaking labor movement somewhere between Marxism and Fascism.

English-speaking labor was not nearly as anti-Christian, violent, militant, or genocidal as Bolshevism. When Labor and FDR took power, churches were not burned; there were no famines or ethnic deportations; the study of Darwinism was not banned. On the other hand, FDR and Ramsay MacDonald (UK Prime Minister, 1929-1935) weren’t fascists.

MacDonald was a pacifist, opposed to Britain’s involvement in WWI, who later denounced the Treaty of Versailles as an impossible burden. At the same time, MacDonald had antisemitic views.

MacDonald supported Zionism, because at the time it was associated with Socialism and the left. However, when visiting Palestine in 1922, he remarked that:

"[The non-Zionist Jew] was the true economic materialist. He is the person whose views upon life make one anti-Semitic. He has no country, no kindred. Whether as a sweater or a financier, he is an exploiter of everything he can squeeze. He is behind every evil that Governments do, and his political authority, always exercised in the dark, is greater than that of Parliamentary majorities. He is the keenest of brains and the bluntest of consciences. He detests Zionism because it revives the idealism of his race, and has political implications which threaten his economic interests."

Churchill made a contrary observation, from an opposing set of values. He declared that, without the idealism of Zionism, Jews would be seduced by Bolshevism (rather than capitalism, as MacDonald feared). Put in the context of the time, MacDonald’s views were not entirely out of place.

Naziism took the additional step of combining MacDonald’s view (Jewish capitalism is harmful, but Zionism is good) with Churchill’s view (Jewish Bolshevism is harmful, but Zionism is good), and finally declared that Zionism itself was evil. FDR took the entirely opposite stance, that Bolshevism, capitalism, and Zionism all had positive attributes, and should be fused together into a single political order.

One of the differences between British Labor and the Northern Democrats under FDR was that classism was a much larger issue in Britain. When MacDonald became prime minister, his appointment of ministers of “working class origins” was genuinely shocking and controversial. Unlike FDR, MacDonald was not able to exercise dictatorial powers in Britain following the Great Depression. His government was paralyzed, leading Sir Oswald Mosely to leave the Labor Party and begin his journey into fascism.

Just as MacDonald was being pressured by Moseley, FDR was pressured by Father Coughlin, a Democratic populist and antisemite. By 1939, FDR used totalitarian powers to ban Coughlin from both print media as well as his radio program.

In response to the Great Depression, there were two major failures in the English speaking world: Hoover in America, and MacDonald in Britain. Both had opposite ideas on economics — MacDonald was in favor of Socialism, and Hoover was in favor of free markets. However, both men failed to erect dictatorships, totalitarianism, or authoritarian regimes. As a result, they failed to meet the challenge of the times, and are remembered as failures.

Fascism vs Communism

General Ludendorff, along with Hindenburg, ran the German war effort in the First World War. In his 1919 memoirs, Ludendorff states the need for the state to take complete control of the economy, and to marshal all workers in service of the state. What is the difference between a man like Ludendorff and Trotsky?

The difference between Trotskyism and Fascism comes down to a disagreement on the nature of race, ethnicity, blood, and soil. However, prior to 1929, the specter of Naziism did not dominate Europe (the Nazis only got 3% of the vote in 1928). Mussolini, for example, publicly repudiated antisemitism in 1923.

Early fascist movements outside of Germany (1919-1923) were not identifiably antisemitic. As late as 1927, the Jewish libertarian Ludwig von Mises felt comfortable to praise fascism:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.1

If fascism was not defined by antisemitism, what was the distinction between Mussolini and Trotsky? Mussolini’s willingness to work with capitalists and the monarchy, in opposition to Trotsky’s campaign against Kulaks, means that fascism was a “half-measure” or compromise between economic totalitarianism and economic libertarianism. In this sense, fascism was “more free” than communism, but directionally, it represented the same “unionist forces” that propelled communism forward.

Still, even if Hitler killed all the capitalists and established direct state control over all industry (as recommended by Strasser), there would still be a cultural distinction between fascism and communism.2 The “total economy” of Ludendorff and the Communism of Trotsky were opposed on Christianity, God, and the importance of “blood.”

FDR

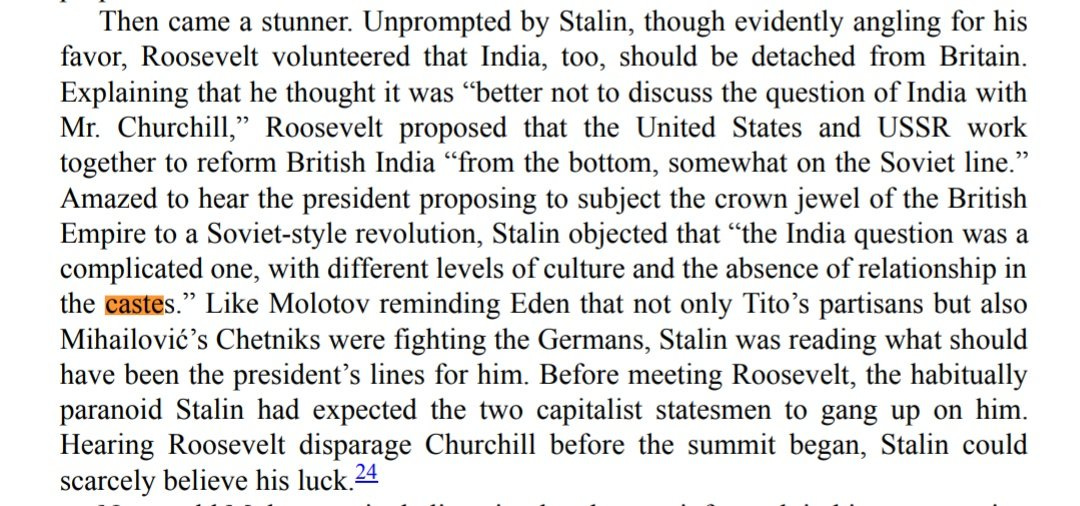

Hanania highlights FDR’s Wagner Act as the turning point in American labor relations. FDR’s ability to appear neither Bolshevik nor Fascist was a delicate balance. Yet in private, FDR was more ambitious, radical, and anti-colonial (on a global scale) than Stalin.

At the time, however, FDR’s domestic policy was extremely conservative, at least when compared with Bolshevism. FDR was ostensibly a Christian; he was also (on the surface) in a political coalition with southern segregationists; his own WASP upper-class origins contrasted significantly with the working-class (and non-Russian) origins of Bolsheviks.

On the surface, FDR’s Democratic Party was in coalition with Christianity, segregation, and American patriotism. Notably, his vice president, John Nance Garner, was a southern Democrat who helped to disenfranchise poor black and white voters with a poll tax. Privately, however, FDR believed in a global revolution against imperialism and the construction of a United Nations Government. Although FDR allied with Britain in WWII, he encouraged Stalin to destroy Britain’s empire.

Part of FDR’s foreign policy was informed by a sense of naval competition between Britain and America.3 Still, FDR’s ideology was closer to Bolshevism than Fascism.

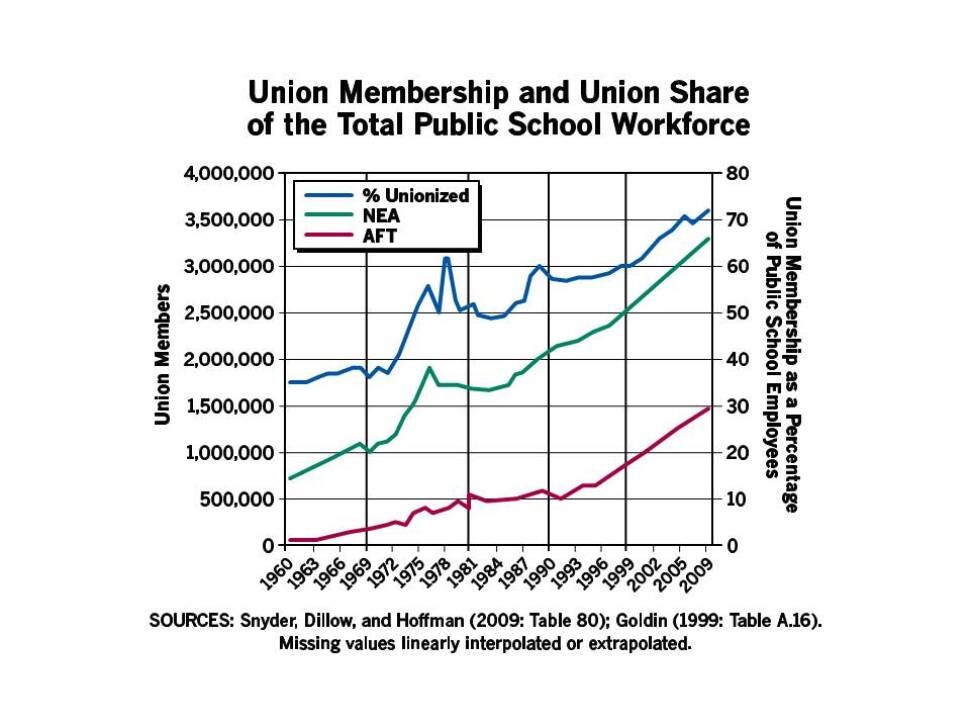

The decline of unions.

Hanania explains that unions “declined as the sectors and businesses that were unionized tended to see much lower job growth.” Hanania is arguing that because unionization hurts businesses, unions have decided to give up their selfish pursuits, or governments cut them loose. But why wouldn’t the same argument apply to the expansion of government itself? Why don’t governments recognize the cost of bureaucracy and regulation to the economy, and start cutting them loose?

Perhaps that is beginning to happen with Trump and Milei. We will see. However, it’s a bit late in the game. Unions have been declining for decades, and Milei has only been in power for a few short years. I’m afraid that when his term ends, even if he appoints a competent successor, some moderate liberal will win back power in 15 years and bring everything back to square one.

Unions cannot exist without government compulsion and force — as a result, they are effectively products of the government, as much as the DMV, social security, and the post office. If unions are backed up by violence at the margins, why would they care about economic efficiency? Why wouldn’t they continue rent seeking? Why wouldn’t they continue voting to inflate their power?

Just to make sure, I did a ctrl-F on Hanania’s article looking for the word “teacher.” What makes teacher’s unions succeed where other labor unions have failed?

By Hanania’s logic, the federal bureaucracy should begin to decline “as governments with large bureaucracies tend to see much lower job growth.” There is a problem of incentives. While Hanania argues against unions from a bird’s eye view, unions themselves have no reason to be convinced and to selflessly stop engaging in parasitism. The question is: what force degraded unions, while government at large has continued to grow?

Additionally, why haven’t communist dictatorships around the world followed the example of the Soviet Union and submitted to capitalism? For example, in North Korea, the Kim family can clearly see that South Korea has economic advantages, yet they have not “de-unionized” their country to become capitalistic. China, similarly, has experimented with some limited forms of capitalism, but still does not approach anything resembling a free market. Why did unions decline in America, and the Soviet Union fell, but communism did not disappear in China, North Korea, or Cuba?

When Jimmy Hoffa was killed in 1982, the prime suspect was the Italian mob. This makes sense: unions are an inherently violent and parasitic institution, just like the mob, and the two were frequent opponents (and bedfellows) throughout the 20th century. But the mob was never successful in quashing labor unions with force. Unions weren’t intimidated by force, but seemingly withered away.

Understanding this is simple. Walk into a car factory. How many workers do you see?4

Or, if you prefer quantitative evidence:

In 1913, Henry Ford had 14,000 full time workers. He had to hire almost 60,000, however, since 3 out of every 4 workers would end up quitting. The total revenue of his company was around $25 million, which is $794 million in 2024 dollars.

Today, Ford has 177,000 employees, but only 57,000 are factory workers. And yet, Ford has a net revenue of $176.2 billion. How did Ford only increase its workforce by a factor of 4x, but it increased its revenue by a factor of 220x? Did workers become 220x faster, stronger, and more efficient? The question is satirical, and the answer is robots. Robots de-unionized the country.

The story is the same for all industries and all factories. Even coal miners and lumberjacks have been replaced by robots. Sure, there are men who operate these robots, but the workforce is significantly smaller and less physical. The only surviving industries for the “blue collar” are home construction and maintenance, because homes are geographically dependent. Whereas a factory can exist anywhere and ship its products around the world, homes need to be built and maintained in specific locations. It’s difficult to build a robot plumber or electrician (for now).5

Robots are a product of capitalism. Without the profit motive, there would be little incentive to invent these incredible machines. Capitalism was so efficient that it was able to fund Stalin’s war machine. 92.7% of Russia's railroad production during WWII came from the Lend-Lease program.6 No capitalism means no railroads; no railroads means no supply lines; no supply lines means Germany wins.

China has robots, and still maintains authoritarianism. The reason for this is that unlike the west, where institutions are strong (people still trust scientists, juries, doctors, police, relatively speaking), in China, all historical institutions prior to 1947 were wiped clean and replaced with the state. Now that trust in institutions in America is declining, we are seeing an increase in “communist tactics” in America: hate speech laws, the militarization of the police, and social media censorship. As America becomes more like China, it becomes less stable, and has to emulate communism in order to compensate. Communism is a means of maintaining stability in a society where there is no traditional religion holding society together.

Efficiency and stability.

Returning to the earlier quote by von Mises, here’s the second half of it:

But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error.

Mises is arguing that the cultural, political, and violent crisis of communist revolution demanded an immediate and effective response that the free market alone could not provide. Force was required. Democracy was suspended. Single party rule, a cult of personality, and militant patriotism were the solution.

In other words, while libertarianism is an extremely effective economic system, it cannot absorb the shockwaves of a political, cultural, or religious crisis. To put it another way: libertarianism is the most efficient means of organizing the deck chairs on the Titanic. But while libertarianism is busy going OCD on the chairs, it is powerless to steer the ship. Fascism and communism leave the deck chairs in a mess, but they steer clear of the iceberg.

This is essentially Curtis Yarvin’s defense of American monarchy. He describes Washington, Lincoln, and FDR as strong executives who governed without adhering to the narrow constraints of the law during a time of political crisis. Had their successors continued to act in this way, rather than submitting to “normalization,” America would have been subject to the same disturbances caused by the liberty of the Roman emperors, caricatured by the excesses of Nero.

If every new president could pack the Supreme Court, suspend Habeas Corpus, and flog his soldiers, each new president would throw the country into chaos. While January 6th never had a chance of succeeding, the idea of it was so destabilizing that 20,000 troops were deployed in DC.

Hanania is correct that unions represent a violation of private property rights. Similarly, the Italian, Jewish, and Irish mob violated private property rights. Unions can be considered violent, criminal organizations. Taken to another level, we can consider police officers to be violent thugs in uniform.

This isn’t to equate the police with mobs and unions (although structurally, there are similarities). But it is to say that societies cannot exist without some degree of the use of force. The ideal of libertarianism is as little force as possible; less force means more market efficiency, which leads to more robots that win wars and create wealth. But libertarianism, as efficient as it is, is not equipped to handle cultural, religious, or political crises.

What if FDR was a libertarian, instead of a “unionist”? What if he held the same views as Herbert Hoover? In that case, he probably wouldn’t have won the election. In this alternative history, maybe a populist like Huey Long would have won the presidency, kept America out of WWII, and let Germany conquer the continent. Or, if the political establishment suppressed all attempts at “unionization,” perhaps a socialist revolution (as was threatened in Germany, Italy, and succeeded in Russia) would have become a genuine threat.

In other words, unionization was the highly-likely result of workers having a much greater share of economic power than they did under feudalism. Feudal peasants did not have the education, agency, literacy, or organizational capacity that was necessary for industrial workers. Industrial workers ran highly complex factories with dangerous equipment. While peasants were essentially irrelevant to war (patriotic peasants didn’t produce any more food than unpatriotic serfs), industrial production was highly subject to the effects of morale, as detailed by General Ludendorff in his memoirs. As the morale of industrial workers came to determine military outcomes, industrial workers began to realize their power, and they stood up — violently.

Between this period of unionization and feudalism, there was an intermediate period of bureaucratization which gave rise to the French Revolution. To avoid historical determinism, we won’t describe the French Revolution as “necessary” or “inevitable.” But the forces supporting the French Revolution made the result highly likely.

The only way to avoid a French Revolution would have been “proto-unionization”: the King of France would have to come to a compromise with the bureaucratic class. In Prussia, Otto von Bismarck kept a close correspondence with the Jewish socialist Ferdinand Lassalle. Bismarck’s belief was that the forces of socialism should be compromised and bent toward the Prussian state. The result was that Prussia, a hotbed of socialism,7 never experienced a revolution.

Prussia expanded state power by pioneering welfare, pensions, and public education. Had Prussia instead repressed these measures, it would have increased the risk of political turmoil. Ludendorff’s criticism of the German parliament is not that it was “too leftist,” but that the state did not exercise sufficient control over media, industry, and political parties. Had Ludendorff’s reforms been enacted, the Germans may have been able to negotiate from a stronger position, and avoid the trauma of Versailles.

In Russia, as well, the government remained aloof and distant from the concerns of socialist intellectuals. In fact, there is even evidence that the Tsar became an enemy of certain factions within the Orthodox church, which led to their relative apathy in the face of revolutionaries. Kerensky seemed preferably to the Tsar — but Kerensky, like Ramsay MacDonald, did not have the power to hold the state together.

According to Professor Mikhail Babkin:

On March 2, 1917, [..] six of the eleven members of the supreme body of church administration [..] decided to immediately establish contact with the Provisional Government, formed that day by the Executive Committee of the State Duma. [..The] members of the Synod recognized the new government even before (!) the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II from the throne, which took place on the night of March 2–3.

The church helped spread communist propaganda describing the false abdication of the Tsar’s appointed successor:

In early March 1917 [.. propaganda] was printed [..] by the Petrograd Soviet [..] under the title “Abdication of Mikhail Alexandrovich.” [.. The] myth spread about the abdication of the Grand Duke.

The Grand Duke stated that he was ready to accept the Tsardom if this appointment also was backed by a vote of support from the Duma. However, Bolshevik propaganda declared that the Grand Duke had already abdicated in order to demoralize monarchists.

On March 7, the supreme body of church administration issued a definition in which it was prescribed to all Russian clergy: “in all cases, instead of commemoration of the reigning house [the Romanovs], to offer prayers “for the God-Preserving Russian and Noble Interim Government”. That is, on March 7, in the absence of the abdication of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich and before the decision of the Constituent Assembly on the form of government, the reigning House of Romanov began to be commemorated in the past tense. Thus, [..] we can say that the members of the Synod overthrew royal power as an institution. [..] the Synod actually proclaimed the thesis of the divine origin of the authority of the Provisional Government.

Obviously, it is possible to criticize the Tsar for not being libertarian enough. Russia was backward and stifled by an entrenched nobility whose wealth was tied up in agricultural plantations, much like the Southern aristocracy before the Civil War. However, it is clear in retrospect that the greatest defense of free markets would have been a more aggressive action in 1917: either the church should have excommunicated all dissenters, or the Tsar should have pursued a totalitarian solution against the wishes of the church. There was no other option by that point.

Again, in hindsight, if the Tsar (like Bismarck) had worked with socialists from the beginning, the 1917 Revolution would have never occurred, since he would have enough socialist allies to legitimize his government. But there was no libertarian, small government solution to the crisis.

Leaving libertarianism.

I was a libertarian, because I was convinced by the logical argument that the free market could best negotiate prices to achieve maximum efficiency. This argument works so long as the government is not threatened by religious, political, or cultural revolutions. However, in the 19th and 20th centuries, as the Church became weak (or even hostile to monarchy), the threat was very real, and governments had two solutions to avoid full communism.

The first, offered by Bismarck, was a half-measure. It involved befriending, collaborating, and compromising with moderate socialists, to take the wind out of the communist sails. Bismarck’s welfare schemes and FDR’s backing of unions in America may have hurt the market, but it also prevented a communist take-over.

The second, offered by the fascists, was to steal or re-appropriate socialist ideas, while at the same time aggressively persecuting the left. Mussolini and Hitler increased government spending in service of the war machine, while putting communists in concentration camps and assassinating their political opponents.

The third option was communism itself. Conservatives like Churchill imagined a fourth option, where no compromises would be made, and both fascism and communism would be defeated. That was a figment of his imagination, and the defeat of fascism meant the victory of communism in Europe.

The ability of capitalism to defeat communism in the Cold War was in part due to its greater efficiency. But it was also due to the western abundance of human capital. Kazakhstan has never been known for its human capital (unless we count the invention of the chariot millennia ago). The Russian Empire always lagged behind western Europe, even before it was communist. Even now that Russia is not ideologically communist, it has still shown an extreme degree of incompetence and corruption in the War in Ukraine that few thought possible.

Putting myself in the shoes of FDR, it is understandable why he would want Stalin as an ally against Britain and Germany: while Britain and Germany might have the human capital to oppose global American domination, Russia would probably return to its historical mean of backwardness. In other words, supporting Russia, a regressive power, against Germany and ultimately Britain, progressive powers, would result in ultimate American hegemony. FDR was proven right in 1989.

Government policies, like money-printing, tariffs, public education, universal healthcare, social security, welfare, or support for unions can all be thought of as a tax. Even though there was no explicit “union tax,” government support for unions effectively acted as a tax on the American economy, slowing growth. Calculating this tax is important, because it allows us to put the problem in perspective.

Would you rather have a Bolshevik revolution where 30% of your population ends up dying after almost 30 years of ideological conflict? Or would you rather slap what is effectively a 10% “growth tax” on your population in order to pacify the revolutionaries and integrate them into a more stable power structure?

FDR’s decision to ally with unionists may have been avoidable. Perhaps if FDR was in favor of free markets, America could have still avoided a communist revolution. But maybe as a result, Hitler would have taken power in Europe: Hitler could not have been stopped without Lend-Lease. A 10% growth tax, or a 1,000 Year Reich? For FDR, the risk of losing Europe was too great, and he chose the populist route.

Today, with the threat of communism and fascism seemingly extinguished, America still finds geopolitical opposition in China. Whether China is truly communist or state capitalist is an academic or semantic question. If Republicans supporting unions allows them to launch a war against China, but being a principled libertarian means that China takes over Africa, which is the correct position?

Of course, a war with China could be disastrous, and maybe a Chinese-led Africa wouldn’t be so bad. At the very least, however, it should be acknowledged that unionization is not a question of mere economics, but has significant political (and therefore geopolitical) implications.

For what it’s worth, I think Trump will lose, no matter how much support Republicans give to unions. So it might not matter anyway.

Mises, Liberalism, 1927.

Deep Fascism and Deep Democracy

A common critique of fascism is that it is not a real political ideology, but merely a hodgepodge of random, arbitrary, historically contingent policies. Fascism was whatever people wanted it to be.

Why Is Globalism "Anti-Colonialist"?

In the early 20th century, Woodrow Wilson introduced the concept of “popular sovereignty” as the official policy of an expansionist United States. On the one hand, Wilsonian democracy was invading Europe and maintaining the Monroe Doctrine. On the other hand, Wilson chided European colonial powers, and demanded the breakup of Europe into microstates, et…

I also thought of oil rig workers, but there are only 6,631 of them, as opposed to 8 million construction workers.

Weeks, Albert L. (2004), Russia's Life-Saver: Lend-Lease Aid to the U.S.S.R. in World War II. Page 9.

Karl Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, which had been under Prussian control since 1815.

“Hanania is arguing that because unionization hurts businesses, unions have decided to give up their selfish pursuits, or governments cut them loose.”

That’s not what I argued. I think these institutions are so pathological that they don’t adjust to reality and end up making everyone but perhaps their corrupt bosses much worse off.

Neither this article, nor Hanania‘s article are actually about trade unions. This one, with its fairly typical conflagration of fascism and socialism believed only by online American libertarians - is about government and state intervention in the economy. Trade unions are about working people who organise, and that’s it. People in those organised unions can believe what they want, otherwise. Many would be socially conservative, and to confuse the working guy with upper class liberalism is as ahistorical as assuming he’s a natural fascist or communist.

That some of these organisations were criminal, that others were coercive and so on is besides the point. That’s true of any organisation, it’s true of the corporate forces (often armed) who acted against the unions, and it’s true of most parties in the democratic system.