Costin Alamariu’s Selective Breeding and the Birth of Philosophy is a controversial bestseller on the topic of Platonism. Alamariu’s chief claims are that philosophy originated from the Greeks; that the preconditions for philosophy originate from a pastoral aristocracy; and that aristocracy can only arise from a class of warriors. This critique will introduce alternative hypotheses: that the Greeks were not the first philosophers; that florists, agriculturalists, and merchants necessarily contributed to philosophy; and that writing is central to the birth of philosophy. Unlike previous critiques,1 I will not employ ad hominem.

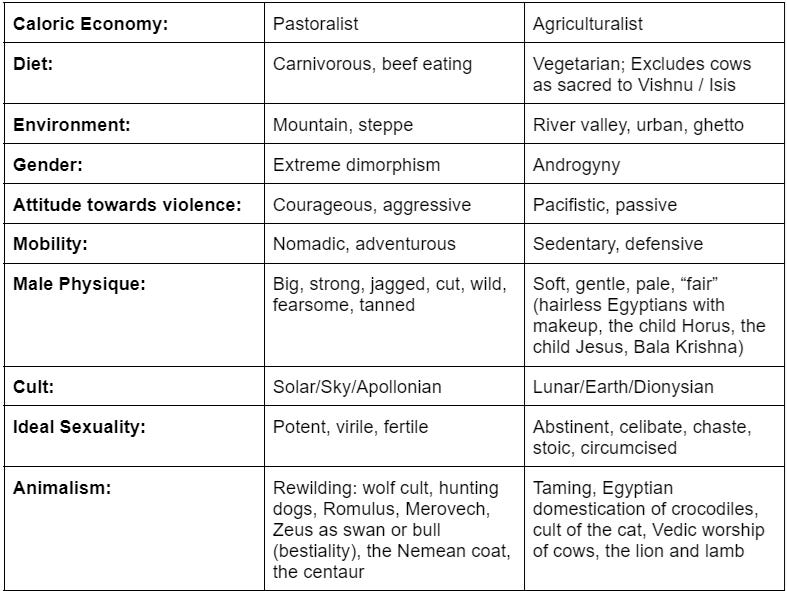

In the Egyptian tradition, civilization is associated with writing, agriculture, respect for law and elders, protection of the weak, and prohibitions on murder and stealing. The Vedic tradition adds to this, saying that man is civilized when he stops eating meat and becomes a vegetarian. In contrast, Alamariu places philosophy in opposition to civilization. Philosophy is the rediscovery of the ancestral spirit of the the koryos within the prison of civilization. The koryos is the “wild band of brothers,” found in the Eurasian steppe cultures: Indo-European, Turkic, and Mongolian. Alamariu also praises the mountainous Tibetans and the African Tutsi as examples of aristocratic, pastoralist warrior cultures.

There are some contradictions in Alamariu’s contrast between “manly” steppe warriors and “overcivilized” androgynes:

According to Herodotus, the chief priests of the Scythians, the Enaree, were androgynous and transvestite.

According to Tacitus, the Germans were especially protective of male virginity until adulthood, as they believed that losing one’s virginity stunted development.

The slaying of the minotaur by Theseus contradicts the idea that the Greeks worshipped the ideal of a “beastialized man.”

The Odinic cult of the berserker, the werewolf, and the representation of the wild hunt, is nocturnal and even lunar. Meanwhile, the chief God of the Egyptians, Ra, is solar.

In the interest of a charitable and good faith argument, I will provide some possible counter-arguments to these apparent contradictions:

Since the Scythians saw the priestly profession as inherently effeminate, they consigned their most effeminate men to that profession;

The German prohibition on sex was not meant to decrease the sex drive, but to ultimately enhance its fullest manifestation;

The defeat of the minotaur represents the Mycenean victory over Minoa — the defeat of the “cow people” by the Indo-European warriors;

Whereas worship of the moon is associated with witchcraft (the Greek Hecate) and the feminine and subtle arts (poison making, alchemy, incantations), the role of the berserker is to rebel and rage against the night. In Greek myth, Apollo, the solar God, is associated with wolves.

Alamariu’s thesis would be more convincing if he attempted to address and then thoroughly demolish these counter-arguments in more detail than I have done here.

Alamariu depicts free or philosophical thought in opposition to dogmatic thought, nomos. Following Strauss, he says that the first philosophical idea is the idea of nature. This is confusing, since Locke, Hobbes, and Rousseau imagined primitive man in a “state of nature.” If the earliest man was already the closest to nature, how was it that philosophy only later began with an idea of nature? To resolve this confusion, the “idea of nature” is clarified as an idea of “differentiation,” as “in-born nature” differentiated from mere custom.2

The differentiation of nature from custom is this: behind cultures, customs, opinions and traditions, there is an objective natural world and an objective human nature which transcends, gives birth to, and is independent of the variety of perspectives. This “naturalistic” view differs from the nomic view. In the nomic perspective, the natural world is best explained according to whatever story is most authoritative, oldest, most traditional, or most popular. In the nomic view, people are not defined as virtuous according to their “natural” traits (intelligence, strength, courage), but according to acquired or educated traits, like respect for elders, respect for the Gods, or memorization of spells. In today’s world, this would be respect for science, experts, academia, and trusted sources.

Philosophy rejects dogmatism. Philosophy is the freedom to question, to be skeptical, empirical, to engage in open argument and dialectical disputation. Alamariu compares this intellectual competition to the Greek agon, physical contest. Pindar praises individual athletes rising above the rest, not on the basis of rote education, but on the basis of their in-born superior physical nature. Pindar celebrates in-born genius, self-deification, and non-conformism. This physical culture provides the template for intellectuals to defy “traditional wisdom” and bring new ideas.

The “doctrine of nature,” which abandons tradition in favor of individual genius, threatens the authority of accumulated genealogies. At the same time, it threatens Athenian democracy and rule by the people. Neither the common man not regressive lineages are safe from philosophy.

For the philosopher, politics is an art. Like other arts (such as the art of war), it could be taught to an extent, but the best are born with inherent talents. If a painter fails, he brings down his household, but if a ruler fails, he brings down society. Only those with the greatest nature for excellence, arete, are fit to rule. This question was central to Plato’s thought, since the defeat of Athens by Sparta led to the tyranny of Critias and threw the entire political order into question.3

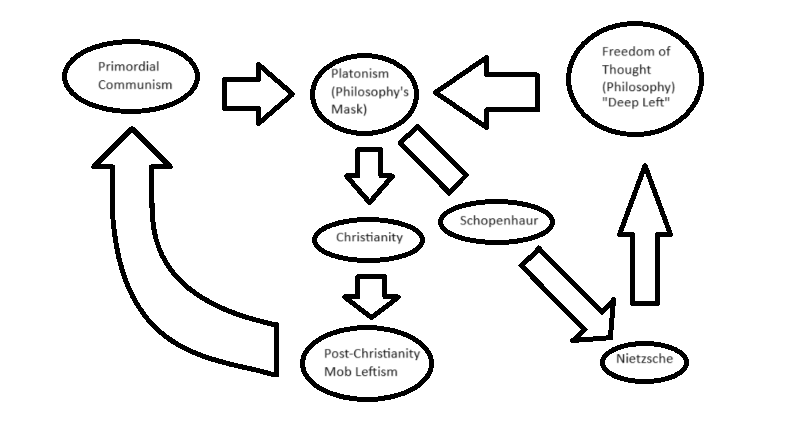

Rather than rule by genealogy or democracy, philosophers sought rule by excellence. In opposing both the nobility and the masses, philosophers were called tyrants. The accusation of tyranny and immorality was dangerous for philosophers, and led to the death of Socrates. Alamariu argues that Plato masked philosophy with “temperance and justice.” Plato consciously (conspiratorially) created a new priest class and a new religion to seize moral authority and protect philosophy from the moral panic of democrats and traditionalists. With this mask, they could manipulate or guide the city, become its rulers, and make the city safe for philosophy.

Deep Leftism vs Mob Leftism

Jesus Christ made a distinction between the dead law and the Holy Spirit. Whereas the law is an unchanging prison, the spirit is alive, electric, and vibrates at a higher frequency. The Holy Ghost is present in the real world and can be physically felt. Sigmund Freud reframed the dynamic between spirit and law as eros and thanatos. Whereas the spirit the source of all life, the law is the source of all death. The spirit is the Deep Left, while the law is the Deep Right.

This use of “left” and “right” is confusing in view of the petty so-called leftism of the present day. But leftism is ancient and far precedes the French Revolution. The leftism of Caesar overturned the republican order and consolidated the state into an empire. The leftism of the colonist or explorer risks everything for a chance at tyranny over new lands. The leftism of Hegel, Voltaire, Columbus, Galileo, Rudolf II, Plato, and Socrates. None of these people called themselves “left” or “right” but their opponents correctly identified them as attacking tradition.

Nietzsche’s critique of Plato is that this original “Platonic” or “Socratic” freedom, which was not inherently egalitarian, was then caught in a victimary vortex by Christianity. Ancient leftism, classical liberalism, was flipped upside down by Christian fanatics. It became a tool of the mob against higher thought. Free thought reemerged in Europe out of the weakness of the Catholic church. Yet as Christianity died, it unleashed post-Christian mob violence in the French Revolution. The “leftism” of the French Revolution is a return to the most brutal form of “overcivilized” egalitarianism.

The paradoxical nature of post-Christian leftism, which simultaneously combats tradition, while at the same time reinforcing egalitarianism, is a prominent feature of the proto-Protestant movement. John Wycliffe’s Bible (1381) can be seen as an attempt to free England from nomic Latin, to engage with the Bible as a series of propositions and ideas rather than as formulaic series of repetitions. Yet Wycliffe was associated with rabble rousers like John Ball, who proclaimed, “from the beginning all men by nature were created alike.” Ball recommended “first killing the great lords of the realm, then slaying the lawyers, justices and jurors, and finally rooting out everyone” who oppressed the masses.4

The association between “freedom of thought” and “mob rule” is a prominent feature of post-Christian leftism, but the marriage between the two is an extension of Platonic propaganda. Empirical or skeptical inquiry does not necessitate the worship of the masses, or the enshrining of universal “utilitarian” morality. The connection between the two results from a moralistic cover or balancing act. When the old aristocracy is questioned, the questioner must provide a new justification for authority. As Athenian democracy was questioned, the new justification for the rule by the philosopher was an appeal to temperance and justice. “Proto-protestants” like John Ball approached justice as the goal rather than as a means of power, and worshipped equality as the highest form of justice.

But John Ball’s egalitarian leftism was not the only game in town. Renaissance men like Giordano Bruno questioned established authority, but also the equality of all men.5 The deep leftism of Hegel, Voltaire, Kant, Schopenhauer or Darwin supplanted egalitarianism with a naturalistic view of man, of man as an animal, with variations from birth. Egalitarian leftism found success in the American and French Revolution, in the phrase, “all men are created equal.” In practice, however, the American founders limited the franchise to land owning white men. In France, mob leftism was put down by Napoleon, who is thought of as “right wing” by contrast, but could be viewed as a champion of deep leftism over mob leftism.

Despite the intentions of the founding fathers to create a lasting system of governance, the “exoteric” principles of equality have cannibalized the “esoteric” principles of free thought. The Enlightened tyrants of Europe gave way to parliamentarism, and socialism arose as a new religion.

The confusion in academic critique to identify Nietzsche as “left” or “right” stems from an inability to distinguish between the mob-left and deep-left. Other examples of the ambiguity of classification include Wilhelm Marr, an atheist, democrat, and 1848 revolutionary, as well as his contemporary, Richard Wagner. Both were “men of the left” in many respects, who are now thought of as “men of the right.” The truth is that their “leftist spirit” persisted and survived even as they lost their egalitarian prejudices.

The bifurcation of the term “left” into “mob” and “deep” components has little practical application for day-to-day politics. What passes as “left” is uncreative, cowardly, and views science as proclamations on stone tablets from bureaucratic, academic priests. Mob leftism is the fiercest defender of dogma, on par with, and often allied with, primitive tribalism. The spirit which challenges established authority, seeks truth at any cost, and thinks freely, this is the deep-left. Yet in opposition to the mob-left, it passed for “right wing.” Things are so obfuscated by lies and wordplay that unraveling this wordplay will be mired in the same swamp.

While the Straussian origins of Dr. Alamariu's thesis are, in practical parlance, “right wing,” his attempt to discover the origins of philosophy is an attempt to discover the origins of the deep-left. That deep left, from the Aegean to India, liberated humanity from the eternal stasis of the deep right, the supremacy of nomos. This concludes my introductory and semantic remarks.

Readers of Deleuze may recognize custom as “repetition” and nature as “difference.”

Although modern depictions of Socrates might imagine him as effeminate or nerdy, he was characterized by Plato as a veteran of the Battle of Potidaea, in which he saved the life of Alcibiades.

Dobson, Richard (1970). The Peasants Revolt of 1381. Pages 373–375.

Bruno was one of the first to suggest polygenism based on the physical varieties of man.